THE BACKSTORY: THE ASD BACK-TO-SCHOOL BLUES

BY JUDITH NEWMAN ’81

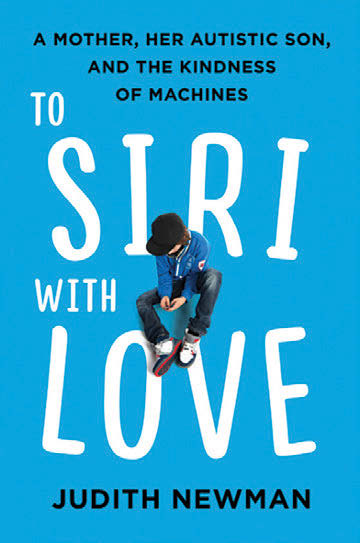

Judith Newman ’81 is the author of To Siri with Love: A Mother, Her Autistic Son, and the Kindness of Machines (Harper Collins, August 2017). She lives in Manhattan with her twin sons, Henry and Gus. Learn more at judithnewman.com.

Me: “Honey, it’s going to be great! Let’s go shopping for…”

Gus: “No.”

Me: “You can’t wear the same tshirts you’ve worn for four years.”

Gus: “Nopers.”

Me: “Gus, you’re fifteen. You can’t keep carrying an Elmo lunch box.”

Gus: “Mom, you know I just like the same old things.”

Me: “Well. Okay. Let’s look at your new fall schedule.”

Gus: <trembling lip, slow tears>

Every kid has a tremor of nerves at the start of a new year. But if you’re autistic like my son Gus, there is nothing about the word “new” that holds joy. The word he loves to hear is “same.” Same is Gus’s jam— and there are so many kids like him.

Think back to how you felt the night before the new school year began. Your mind raced: Are the classes going to be too hard? Is that jerk in homeroom going to remember last year’s Incident in the bathroom? And, if you were about to be a senior in high school: Oh my God, will I go to college without even kissing anyone?

Okay, maybe that was just me.

Still, though, there was the thrill of the fresh start. The day I went to buy new school supplies was one of the highlights of my year. Okay, that did not sound as pathetic as it does now when I see it in print. But at any rate, think about your own back-to-school sense of anticipation.

This thrill does not exist for Gus. While his neurotypical twin brother Henry is thinking about school clubs to join, at 15, Gus is clinging to the shores of childhood, desperately hoping nothing changes. He actually loves seeing the kids he knows—but who else will be there, and will they want to text with him? (That is his current definition of friendship—people who will text. This presents some unfortunate situations with telemarketers.)

For the past five years I’ve started the school year by asking him if he is ready to give away his hundreds of Thomas the Tank engines, NYC subway cars, toy buses, and stuffed animals to younger—far younger—kids. “Maybe next year, Mommy,” he says cheerfully.

In spite of my exasperation, I have to remind myself: There are actual, neurological reasons why Gus and kids like him are so fearful of change. A recent article in The Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders explained why up to 84 percent of children with autism have high levels of anxiety and up to 70 percent have some sort of sensory sensitivity: They are lousy at predicting the future. They tend to miss the cues. But it’s not like they’re golden retrievers, living forever in the present—they know perfectly well that there is a future. So combine these two concepts—knowledge the future is coming and being horrible at figuring out what it might be—and you can see how knowing your classroom schedule will be the same as last year’s, or knowing you have the same lunchbox, might be immensely soothing.

When Gus was little, he failed abysmally at those sequencing tests where you’re asked to put story cards in a logical order. He’s not much better at them now, because with people on the spectrum, the ability to infer is damaged. So it must be an awfully good feeling for Gus to know what happens next, which is part of the reason he still watches the same YouTube videos a thousand times, whether they’re tornadoes or Sesame Street. Not that the average kid doesn’t enjoy re-reading the same books or hearing the same song over and over again, but with Gus, it’s a desire for same that’s a different order of magnitude. Remember the fun of going to Rocky Horror Picture Show and mouthing the lines of the characters? Now imagine you want to do that with every movie or commercial you enjoy. Last time I checked there were 347,026 views of “Top 8 Disney Villain Laughs.” I’m pretty sure 347,025 of them are from Gus.

In The Loving Push, Temple Grandin—an autism activist, animal scientist, and probably the most famous person with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)—argues that parents of autistic children need to know how to get their kids out of their narrow grooves. Get them off their safe computers, for example, and get them out into the world to expand their interests and conquer their fears. As I read the book, I realized the sagacity of what she was saying: If I don’t do something soon, I’m pretty sure I’ll be seeing Gus on a future episode of Hoarders, happily nattering away about his inanimate “friends” while picking his way through piles of toys stacked to the ceiling.

But even with these worries, I try to don my Autism Mom goggles, which allow me for see two things. First, these items he can’t relinquish have feelings, and perhaps souls, as far as he’s concerned. I flash back to a day many years ago when there was a bus strike. Gus sat in his room, sobbing. “Honey, what’s wrong?” I asked. (I thought maybe he was worried how he’d get to school.) “Mommy, the buses,” he said, through heaving sobs. “The buses are SO SAD.”

And second? Well, I remind myself of the innate sweetness of his desire for familiarity over novelty. When Gus loves something, he loves it devotedly and always, whether it’s his moth-ridden t-shirts or his mother. He has never said a harsh or unkind word to me. How many mothers of 15-year-olds can say the same?

Gus goes to a wonderful school that does everything it can to help their kids cope with change. Still, his fears, and his desire for sameness, will always be with him.

Recently, a friend was helping Grandin complete a book project. To get the job done, he said, he and Grandin spoke every Sunday at 11 a.m. Not 11:01 or 10:59—11 a.m. One day he told Grandin he might not be able to make their usual time that week. There was a pause. “So, we’ll talk at 11:00 a.m.,” she said.

The secret of life is not to bemoan our kid’s differences, or try to eradicate them. It’s to help them navigate, with those differences, through this world.

Judith Newman ’81 is the author of To Siri with Love: A Mother, Her Autistic Son, and the Kindness of Machines (Harper Collins, August 2017). She lives in Manhattan with her twin sons, Henry and Gus. Learn more at judithnewman.com.