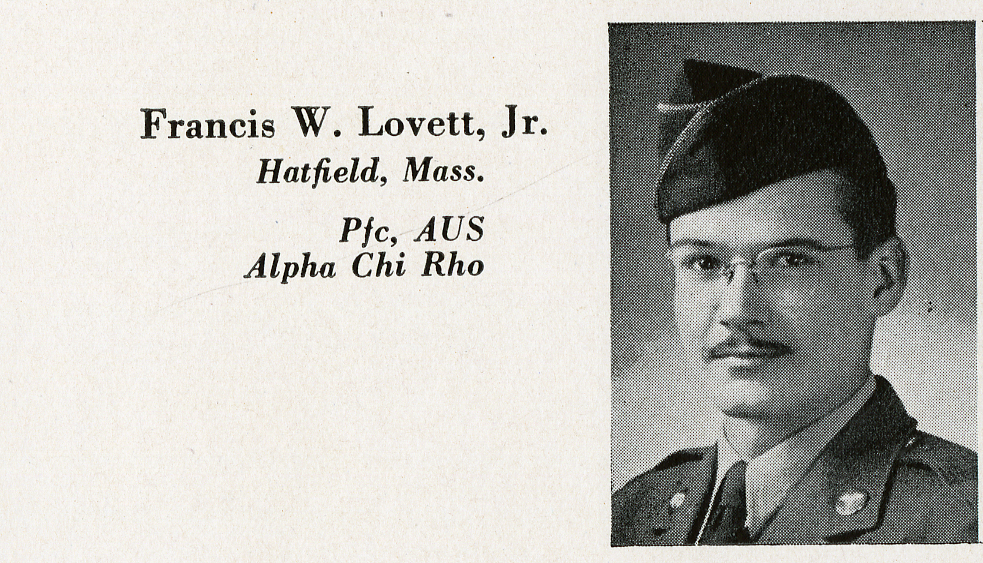

Three Bronze Stars: Lovett ’45 Recalls WWII Medic Service in Italy

Francis Lovett ’45, who graduated from Wesleyan in 1948 after serving with the elite 10th Mountain Division in Italy during World War II, explains how it was that he came to receive three Bronze Stars for his service. A raconteur with a dry sense of humor, Lovett earned his Wesleyan degree in English with distinction, and a master’s in creative writing at Northwestern. He enjoyed a career in education that spanned more than 50 years.

The First Star

From my arrival in March 1943 at Camp Hale, all my physical and medical training was with the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment until the division was moved to Camp Swift, in Texas, for flatland training prior to going to Italy.

The army decided to repair my chronic shoulder dislocation, and I was still in the hospital when the 86th left for the VA port. The next day, I was released into the 85th Regiment and was on my Christmas way to Naples and immediately up the coast to Leghorn, then inland to the Appenine hill towns, where scouting patrols began to probe for routes of ascent against German strongholds on Riva Ridge and adjacent Mount Belvedere.

In February we took Riva Ridge by night, climbing the cliffside believed by the Germans to be unclimbable. Next we assaulted and kept Belvedere, where my mended shoulder was injured, but I remained with my F Company during a lull in action while we took in replacements for casualties.

During a brief time in early March, F Company was in a small valley churchyard. One morning, our lookout in the church steeple saw a woman coming from the wooded hill, and raised the alarm. She came directly to me and touched the red cross on my helmet, begging for help for her bambino who had stepped on a land mine. My Italian was good enough to get her name (Ada Padrini) and a general sense of her house direction, which I reported to the officer in charge, and volunteered to go with her to help. Permission given, I began the climb, following the woman’s rapid pace for about half an hour.

I began to see German wire and scattered pieces of containers and vehicle tracks. I knew I was behind enemy lines and wondered if I had been set up for a prisoner take. About then the woman paused at the top of the ridge, pointed down to where I could see a roof, and said flatly, “Due Tedeschi [two Germans].”

I followed her down to her stone farmhouse, where two Germans sat next to a makeshift litter whereon a young teenager lay moaning. I went at the foot, ignoring the Germans until the younger one began to assist. We talked in French as best we could, and soon had the boy bandaged and quieted with a shot of morphine.

I learned that my assistant was a medic, a five-year veteran entirely out of medical supplies, who had been left to stay with the older rifleman suffering from combat fatigue. We talked about “next,” and I persuaded them to come with me by promising that “POW” meant “mowing grass” in Texas, where a swimming pool was standard. Ada Padrini called out, and half a dozen men materialized out of the woods. I told the rifleman to leave his rifle; he smashed it against the stone house, and we took off.

About an hour later we got back to company headquarters. I turned the parade over to authority, and got the bambino back to rear medical attention. The next day the mother hiked down to give me a chicken as thanks. I boiled it in my helmet and shared the feast secretly and solely with the lookout man. A few days later, Gen. Mark Clark pinned a Bronze Star to my blouse.

The Second Star

The second award was for an early April incident. I had been sent back to rear echelon hospital because my shoulder had not mended well. There, I was labeled unfit for combat and reassigned to limited service. I protested to no avail and decided to quit the hospital, hitchhiked back to the front, and found my batallion just in time for a major assault.

I volunteered to go with Captain Paul Gaffney to establish a forward aid station. That involved my crawling through a mined area and being annoyed by a sniper’s using my red cross as a target. I remember wondering why he was trying to take me out without knowing my name, and did he know about the Geneva Convention rule?

Once clear, I waved Captain Gaffney in (another story entirely) and we two went to work for some noisy and bloody hours.

I didn’t know that I had been awarded that Bronze Star until I was back on campus in early ’46 because our final push across the Po River and to the Alps, followed by German surrender in May (15,000 prisoners to manage), going into Trieste to thwart Tito’s plans, and my being moved to 10th Special Troops, before coming home in early August, all kept me ahead of the citation for about seven months.

I had a special admiration for Dr. Gaffney, who assured me on more than one occasion, “Lovett, you’re crazy.” But we worked well together, a Celtic duo.

The Third Star

The third award came about 30 years ago, by mail, with no citation, along with all my service and campaign medals. The Bronze Star medal has two oak leaves and the valor device attached; my name is engraved on the reverse side. No one has ever explained the third medal—perhaps for the combat medic badge? Perhaps for participating in every combat engagement the 85th made? Perhaps for . . . ?