Man in the Middle: Sid Espinosa ’94

Working in the White House and with Attorney General Janet Reno. Directing global philanthropy for Fortune 50 companies. Serving as mayor of Palo Alto. For Sid Espinosa ’94, very different roles serve a common end: trying to leave the world better than he found it.

If there’s an intersection, there’s a good chance you’ll find Sid Espinosa in the middle of it.

Espinosa’s years in public service, private industry, and higher education have shown him that the greatest opportunities for impact come at the crossroads of ideas and disciplines. Initial credit, however, goes to his parents for inspiring his bent for action-oriented work and sense of civic responsibility. His father Abel, a proud Mexican immigrant, highlighted for young Sid the importance of citizenship as a social contract—with great American opportunities comes an obligation to engage and make sure one’s country remains strong. Where most view retirement as a chance to relax, Espinosa’s activist/educator mother, Janet, used hers to enroll in the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic and Honduras, and then moved to Ghana to work with children rescued out of trafficking situations.

“Throughout my youth, my mom said that, while people pursue different professions for different reasons, I’d most likely find fulfillment in roles that were about impact and change,” Espinosa says, “where I could be a leader, giving voice to those who felt voiceless or unheard, or standing up against inequality or injustice.”

While Espinosa admits he didn’t embrace his parents’ guidance right away, the seeds of action and advocacy they planted ultimately grew into a deep-rooted interest in civic engagement. After studying government at Wesleyan, Espinosa moved to Washington, D.C., to work at the White House and then for Attorney General Janet Reno at the U.S. Department of Justice. He then enrolled at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government to study public policy. There he saw how the philanthropic sector represented an area “where an incredible volume of resources was being invested in some of the world’s most pressing problems in smart, effective ways,” which led him to a role as Director of Global Philanthropy for Hewlett-Packard in his native California. As he was learning to leverage his role at a well-resourced private company across governmental, public affairs, and philanthropic sectors, he was also becoming active in his local community, serving on nonprofit boards and working on ballot measures.

“Before I knew it,” he recalls, “I had people saying, ‘You should run for office and implement some of these changes. Why don’t you get in there and start leading the change?’”

In 2008, Espinosa did just that, and was elected to the Palo Alto city council, eventually becoming the city’s mayor—and, at age 38, one of the youngest mayors and the only Latino elected in the city’s history. Compared to his time in high-level policymaking in D.C., his tenure as mayor represented a chance to make a tangible, day-to-day difference in the lives of his constituents.

Today, Espinosa is the Director of Philanthropy and Civic Engagement for Microsoft. His work is nothing if not intersectional, harnessing ever-evolving technology to empower the same kinds of movements he has supported in his public sector work on an even greater scale. He took time away from these efforts for a wide-ranging, in-depth conversation.

Your current work and this issue of the magazine both focus on civic engagement. What does that term mean for you?

Sid Espinosa: It’s important to clarify what we’re really talking about. While civic engagement usually means some form of addressing community, societal, or public concerns, it can mean very different things depending on the context:

- Civic Commitment and Duty, which come in the form of contributions to your community, neighborhood, or city, such as voting or holding political office.

- Civic Skills, where we consider questions like: How are we cultivating and strengthening our democracy? What tools are we giving people to do that?

- Civic Action, which considers how easy we make it for people to participate in these activities like voting, mobilizing, or service learning.

- Social Connectedness, which as a broad brushstroke is about how we weave civic-minded individuals and organizations together as a culture and society.

How are you thinking about the current U.S. political/social moment, having closely studied government and given your work in the public sector?

SE: These days, our U.S. civic life and democracy might seem perilous. But it’s important to study history because it so often cycles, not so much in the exact circumstances or people involved, but in trends, repetition, themes. When I hear people say the country’s never been more divided or the violence is unprecedented—if you look through history, there are many examples, and recent examples, where things were worse. When, for example, our president and civil rights leaders were being assassinated or driven from office, or unemployment was higher, or we were at war. We should always look back to put things into context. These times seem bleak, but I am hopeful. We’re a resilient nation and people. I’d also highlight that real and meaningful changes come through struggle and tumult, especially changes in civil rights. Unfortunately, that’s often what’s needed for real breakthroughs.

That said, I also think that we all need to pause and reflect on the positive and negative roles of technology in our fast-changing civic life. More people are connected to more information. We can engage and mobilize more people, more easily. We can have greater transparency in government and we can empower citizens in new ways. But we have also created an entirely different civic town square. Traditional media and trusted news sources are struggling to maintain credibility and even survive. We’re in echo chambers of social media discourse, hearing from others like ourselves at unprecedented volumes. There’s so much false and unchecked information being amplified at lightning speeds, and we don’t yet know where this will lead. These factors and others are starting to fundamentally erode trust in government and public institutions, and that can be disastrous for a democracy.

How can we best handle this new technology-influenced change? What should civic engagement look like at this moment?

SE: Well, it’s not like things haven’t changed quickly in the past. Look at how Roosevelt used the radio to reach a country directly through his fireside chats. Kennedy understood the potential power of television and smartly leveraged the new technology in his campaigning, like his debate with Nixon. A lot of people argue that President Trump understands how to connect to the populace through social media like Twitter in ways many others in public life can’t even comprehend, let alone lean on. We must better understand how technology is affecting our civic and social life before it fundamentally alters our civic institutions and norms.

Last year, Microsoft President Brad Smith released a book, Tools and Weapons: The Promise and the Peril of the Digital Age, which highlights how technology can be used for good and also be weaponized. From privacy concerns and facial recognition to artificial intelligence and the appropriate uses of data—you can see how today’s technological advances could quickly and fundamentally change our public lives and our social fabric. I joined Microsoft because of its global leadership on thinking about how technology could help address a host of societal issues—reskilling workers and computer science education, racial equity and empowering underserved communities, environmental sustainability, accessibility for the disabled, humanitarian assistance. It’s been an incredible journey.

Technology is not the answer or a panacea. It’s a tool. Unfortunately, when it comes to civic engagement and government, the pace of technological change and how technology has permeated every aspect of our lives, stands in sharp contrast with the slow pace of governing and policymaking. Frankly, most policymakers lack fluency in technology and its impact on civic life, let alone how tech should be regulated or connected to government. This is one of the reasons why I’m excited about how today’s college graduates, who are digital natives, will shape our use of technology in democracy. We need them at the decision-making table now. Yesterday. It’s very much a call to action, a real need, as we encourage and empower the next generation.

You’ve had a variety of distinguished educational and professional experiences. How do you think about having an impact across that spectrum?

SE: Isn’t that the goal? Leave this world better than we found it. Make a positive difference during our short time here. At Microsoft, as we tackle the aforementioned global issues, we look to empower leaders and organizations who are having real breakthroughs. These leaders never cease to amaze me. And more often than not, I find that today’s most effective social-impact leaders are successfully leading across sectors. We can no longer rely on one sector for the fix, but understanding differences in incentives, language, budgets, timelines, let alone power and bias, is tough. I think that Wesleyan grads are especially adept in this work. So often civically minded and action oriented, their liberal arts educations help them appreciate complexity, creativity, resilience, etc., in ways that are not always obvious.

You were recently part of a panel discussion with President Roth and other alumni of color discussing ways to build an anti-racist community. It was interesting to hear several members of the panel highlight the importance of private sector work in strengthening community. Can you expand on that?

SE: That discussion featured leaders (myself excluded) who are well-recognized nationally as change-makers. They talked about seeking careers that bettered communities and facilitated breakthroughs on social issues, and throughout their careers they’ve found varied places to do that, from nonprofits to government to educational institutions, and now for several, to the private sector. But this issue is broader than just sectors. Today’s college students will not have a single career track. They won’t get four years of training and be ready for a lifetime in a single company, for instance. Instead, we need to empower students with the skills to thrive in whatever sector they’re in at the time, knowing that it’s likely that they’ll move between them. We need to make sure we’re preparing students to lead in each of those sectors and across them.

Is there a way for students to seek out opportunities to be those agents

of change?

SE: While I value my liberal arts education, for some, liberal arts training can make it tough to figure out career choices. I hear from mentees at Wesleyan: “After graduation, I’m considering the Peace Corps, but law school also sounds appealing, or should I do consulting to learn about various sectors, or should I teach English in Japan for international experience? What’s the right choice? Where can I make the most positive change?” We liberal arts learners have so many interests and passions. We appreciate inherent trade-offs and we don’t want to make the wrong choice. We see so many community needs and can’t figure out where and how to have the biggest impact.

Of course, positive impact can be realized in all sectors and in various work environments, but we each need to determine in which environments we thrive—and recognize that those may change over time. Some people love fast-paced startups where they’re able to effect change immediately. Others thrive in large organizations where there’s defined structure and more resources. Others need creative spaces. My sister Tami (Espinosa ’97), for example, who is an award-winning educator, has been both a teacher and a principal, has real impact and tangible impact in her classroom, and she gets her energy from those kids. She wouldn’t enjoy sitting in an office and staring at a screen all day, like me, no matter what the impact.

Two other quick points. Mentorship is critical. We all need to have mentors and be mentors. And finally, if you’re going to work in the social impact or civic engagement space, plan ahead for the emotional exhaustion. Think about self-care and how you stay healthy. Build a very strong support network. Recognize that most of these issues will never be solved. You can spend a lifetime tackling homelessness or climate change, and frankly, it might be worse when you’re done. It’s important to understand that you’re in a relay race where others have come before you (so be sure to understand what they’ve done) and you’ll be running for a short period (so get focused on finite goals), and then you’ll need to pass the baton (so always do succession planning). Social impact work is important and rewarding, but you can’t let the enormity of the issues overwhelm you.

We’re in a presidential election year. What was your experience as an elected official and how did it compare to your work at the White House?

SE: Serving in public office is wonderful. When I was in classrooms talking to kids about the city, they’d often ask: What’s the difference between being mayor versus being in D.C. and working in the White House? And I’d say that at a federal level, you can work on issues that impact millions of people, that are part of history, and are large and sweeping. But you’re also a piece in a larger machine. At a local level, people will come to you with all sorts of challenges and opportunities and you can help them directly. You can roll up your sleeves and drive the change. On the flip side, at a local level you must be ready for the day-to-day engagement—for someone talking to you for an hour about the pothole in front of their house. The minutiae of local public service drives some people nuts. But I loved it.

For many people, their government engagements seem limited—going to the DMV, voting and paying taxes, filing for a permit—but the reality is that we’re all engaging with government all day, every day even if we don’t know it. I loved talking with students about choices we were facing, like whether we should build a recycling center on parkland, or how wide the sidewalks or bike lanes should be if it meant no parking for local businesses, and so forth. Everything around us requires decisions, often by government. Being an elected official means being at the decision-making table for these policy choices, and that is exciting and important and, frankly, fun.

Any further advice for current students or recent graduates about how they can make an impact?

SE: VOTE, VOTE, VOTE! That’s a critical problem in every election. Recent elections have reminded all of us that even a few votes can tip the results.

Consider spending time in public service. If you haven’t worked in government, it can sometimes seem nebulous and confusing, maybe even corrupt. But if there are problems in our civic structures and institutions, it’s incumbent upon us as citizens to work to fix them. To not get involved because of these hurdles fails to recognize how our system works. My time in government led to some of the most rewarding experiences in my life. Consider starting small and local. Register others to vote. Participate in local ballot measures that you care about. Join a campaign for somebody who you believe in, or run yourself.

When I first ran for city council, I took my little brother and sister (who at the time were elementary school–aged kids) with me as I knocked on doors and talked with neighbors about the issues facing our city. It was such an eye-opening experience for them, seeing that most campaigning is just neighbors talking to each other about the kind of community and society that they want to live in. And isn’t that the real goal of civic engagement? That we work together in community to address our societal needs. We all have a role. We’re in this together.

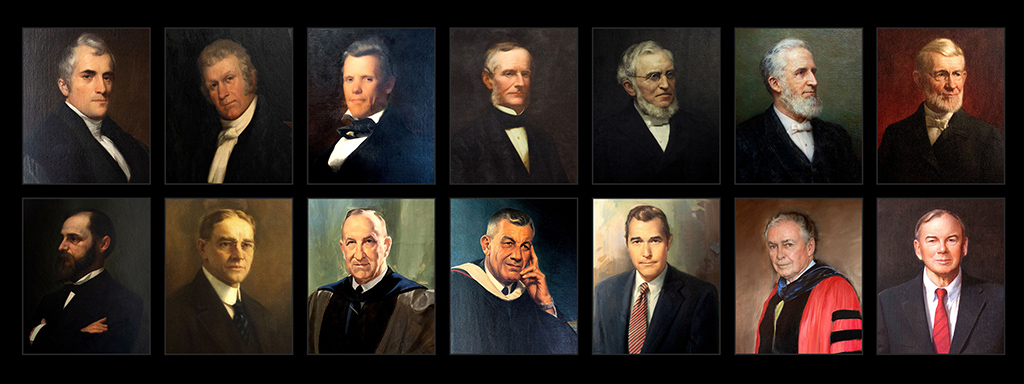

Read more: Espinosa’s collection of past election memorabilia serves as a reminder to keep both the past and the present in perspective.