Mushrooming with Melany and Ellen

In a new children’s book by two Wesleyan alumnae, mushroom foraging becomes a gateway to the joys of nature.

Ever since she was a kid in the woods plucking morels and chanterelles, searching for mushrooms has meant something special to Melany Kahn ’86. For the last 20 years, she’s led school groups, nature center programs, and her own children around southern Vermont to identify, collect, and cook wild mushrooms. Sure, she’s converted more than a few “mushroom scoffers,” as she calls them. But mostly, Kahn uses her fondness for fungus to help young people discover a larger love of the outdoors.

“Having something to look for and focus on—having this treasure hunt—is a wonderful way to connect to nature,” she says.

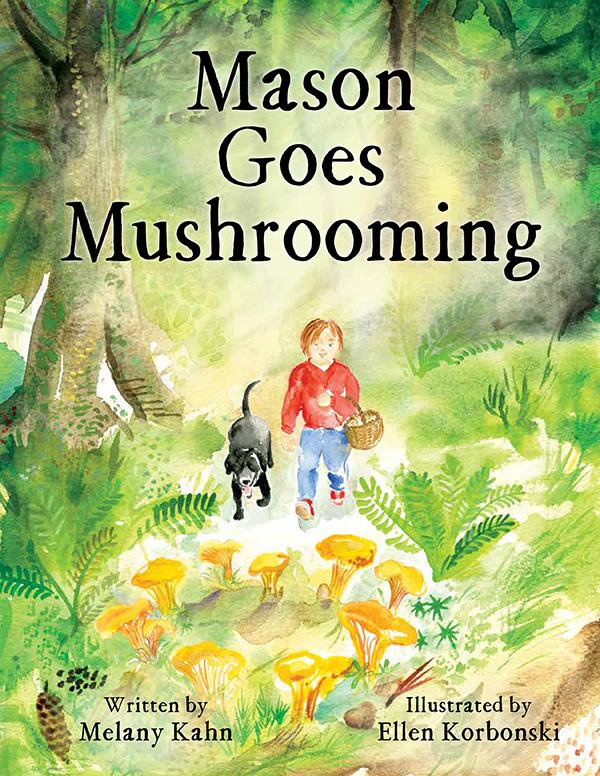

That sentiment guides the 32 pages of Mason Goes Mushrooming (Green Writers Press), a children’s book written by Kahn and illustrated by fellow Wesleyan alumna Ellen Korbonski ’85 released in October. Through Kahn’s inviting prose and Korbonski’s vibrant watercolors, the story follows a young boy (named after Kahn’s son) and his dog as they hunt for easy-to-ID mushroom varieties, prepare recipes, and absorb the four-season wonders of the woods along the way. “It’s a celebration of engaging in the natural world, at a level that kids can manage,” Kahn says.

Though there’s a mycological renaissance going on—with mushrooms seemingly everywhere from gourmet restaurants to high fashion to documentaries on Netflix—Kahn’s interest began while learning the finer points of foraging from her parents (and world-renowned painters) Wolf Kahn and Emily Mason. Later, at Wesleyan, she studied creative writing and struck up an acquaintance with Korbonski, who pursued English and studio art. After reuniting in film school, the two became tight-knit friends and remained close as they each became parents with careers—Kahn as a family mediator in Vermont, Korbonski as a graphic designer in New York.

Korbonski had been designing other writers’ children’s books, when she and her children visited Kahn’s Brattleboro farmhouse for a pandemic Christmas in 2020. “I always had [illustrating a children’s book] in my mind, but it took me a while to be able to really actualize it,” Korbonski says. When Kahn happened upon Korbonski painting a watercolor of a bluebird one morning, she mentioned that she’d been mulling a children’s book about mushroom foraging. Korbonski’s detailed watercolors of nature were a perfect pairing for Kahn’s environmental expertise, and the friends decided to embark on their first true creative collaboration.

Kahn delivered a first draft to Korbonski months later, commencing more than a year of back and forth. The draft’s four-season structure stayed in place, but Korbonski’s evocative illustrations inspired Kahn to revise nearly every word. (“The phrase ‘writing is rewriting’ could not be truer,” Kahn says.) Instead of collaborating through mouse clicks, Kahn printed out pages, cut them up, and collaged them into rough designs, which Korbonski turned into fully realized InDesign layouts. By the time they connected with Vermont-based publisher Green Writers Press, they’d learned how much effort a children’s book requires to appear effortless. “There was definitely a learning curve, but it was exciting because we didn’t have people to answer to,” Korbonski says, noting that an author and illustrator sometimes don’t even communicate in a traditional publisher-ordained pairing. “We could just do it our own way.”

In Mason Goes Mushrooming, foraging is in the foreground. Even so, Kahn emphasizes that there are more important takeaways from the book than inspiring a new generation of mushroom aficionados.

“Just getting folks comfortable and excited about what’s happening in nature is the basis for how we do conservation,” she says. “Until they have their own personal interaction with it, how can we possibly expect them to conserve it and care about it? It’s incumbent on us to explore this world with our kids, and to allow them the generosity and the freedom that nature offers.”