Leading the Charge: 50 Years after Title IX

Four generations of Wesleyan women look back on the advent of federally mandated gender equity in education and the opportunities that sports have afforded them

By Erin Strout

Adrienne Bentman ’74 was one of the first women to arrive on Wesleyan University’s campus in 1970. Part of Wesleyan’s first freshman class to include women after a short-lived effort in 1909, Bentman was one of 100 female pioneers in a class of 1,500 men. Her intention was not only to earn her undergraduate degree and go on to medical school, but to round out her college experience on the field hockey team. After all, she had been a player on her high school varsity squad.

“I arrived at Wesleyan with my cleats, my stick, and my hockey ball,” Bentman says. “After I moved in, the first thing I did was go to what was then Fayerweather Gym and ask where the field hockey coach was. People looked at me with blank stares.”

She eventually found the coordinator of women’s athletics, Barbara Bascom, in the lower level of the facility, where the pool was located. Her office was in a utility closet.

“The mops and the buckets were still in her cubicle. She had a small wooden desk and a small bulletin board and a phone,” Bentman says.

Of course, Wesleyan didn’t have a field hockey team at the time. Or women’s coaches, facilities, or much support at all for an aspiring female athlete. Undeterred, Bentman, now a psychiatrist in Connecticut with a specialty in psychosomatic medicine, took matters into her own hands.

“I created a sign and put it up in the women’s dorms,” she says. “We had to figure out how we were going to get 11 people to make a team, which basically meant anybody who had ever held a field hockey stick or was willing to hold one and run up and down the field.”

Little did Bentman know that two years into her college career, the 37 words of Title IX would eventually change the landscape entirely: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Early Days

On June 23, 1972, Congress enacted Title IX of the Education Amendments, which today seeks to prevent and respond to claims of sexual harassment, sexual assault, and gender discrimination. What it is perhaps best known for, though, is the way it has also vastly expanded the athletic opportunities for women across the country, from elementary, middle, and high schools, to colleges and universities.

Besides the field hockey team, Bentman also joined the crew and tennis teams in those early days. But most of the women’s squads at the time used hand-me-down equipment and old men’s uniforms. They created their own practice schedules and made the best of it, sharing a small, inadequate locker room once used by the men’s faculty members and playing on a field of uncut grass.

“We were attempting to build something on behalf of the people who would come after us,” Bentman says. “We did think of ourselves as pioneers . . . building something from nothing.”

Judy Allen ’77 joined the track team when she arrived from an all-girls Catholic high school, eager for the chance to compete, though, like most young women at the time, not yet familiar with Title IX. Specializing in sprint events and the long jump, Allen, the founder of a marketing firm in Ohio, fondly recalls a spring break road trip to Miami to train in warmer weather. The team sold donuts once a week, door-to-door in the dorms, to pay for the adventure. Despite the funding challenges, Allen remembers how the trip helped the women bond as a team and the pivotal impact sports had on her.

“Being on the team at Wesleyan made a crucial difference in how I regard myself as someone who can meet challenges,” says Allen.

By 1978, Gale Lackey was brought on to serve as head coach of the field hockey team, then as women’s lacrosse coach from 1979 to 1997, before taking the reins of the women’s volleyball team in 1985, a position she held until retirement in 2014, alongside her role as associate athletic director. By the 1980s, the department had added eight new women’s teams and now offers 15 women’s NCAA Division III sports that compete in the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC). Throughout her long tenure, Lackey witnessed incredible growth and opportunities for female athletes at Wesleyan, often propelled by the women themselves.

“I think most of the additions to [women’s] sports were student-driven,” Lackey says. “There were some amazing pioneer student-athletes from the late ’70s and early ’80s that deserve a lot of credit.”

Linda Polonsky ’82 was part of the first wave of female athletes actively recruited by institutions like Wesleyan to join the field hockey team. Once here, she joined the lacrosse team as well. While Polonsky’s college experience was shaped by her athletic opportunities, she recalls that it wasn’t a big part of the campus culture at the time—spectating women’s sports just wasn’t a popular choice, nor were games widely promoted by the University as they are now. Her roommates joked that the “jock” of the floor was off to practice every afternoon and never thought to come cheer her on at a game.

“I have a million vivid memories . . . celebrating with my team together with such joy and camaraderie,” Polonsky says. “Coming together and trying to win—the celebration of playing the best we could and working so hard together, despite not having fans. We were just doing it for us.”

Making Progress

As the University upgraded facilities, expanded its portfolio of teams (women’s golf was the last addition in 2019), and added a number of full-time faculty coaching positions for women’s sports, it became easier to attract more student-athletes to campus, Lackey says. And she began to see competitive expectations change, not just of the players, but their parents, too.

“During my earlier years of coaching and recruiting, I met quite a few ‘Title IX fathers.’ They were looking for the same level of benefits for their daughters as they would expect for their sons,” Lackey says. “Later, there were also ‘Title IX mothers’—those that had participated in athletics and wanted equity for their daughters as well.”

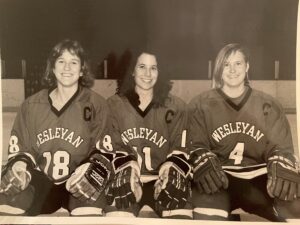

Jen Heppel ’90 came to Wesleyan as a talented figure skater and because of that skill on the ice, was convinced to join the fledgling hockey team. Her lack of experience wasn’t an anomaly at the time—not many women played the sport back then, nor did the NCAA sponsor it. Nonetheless, becoming a student-athlete influenced Heppel’s future deeply—she’s now the commissioner of the Patriot League Athletic Conference. She believes that the attitudes her colleagues have toward Title IX have altered significantly since Heppel and her teammates suited up (in the men’s leftover gear) in the late 1980s.

What was once perceived as a policy that potentially reduced opportunities in men’s sports (Lackey recalls many athletic directors warned that Title IX would “kill college football”) is now often seen as a law that creates a better experience for all.

“Early on in my career, you’d talk about Title IX and you would get almost a physical reaction from people in the room because it was perceived as an obstacle to doing business,” Heppel says. “You’d just see the body language when you were trying to be the person in the room advocating for equal opportunity, and that has changed significantly. Equity and opportunity are ingrained into the conversations.”

Fifty years after Title IX first passed, Grace Devanny ’23, a psychology and neuroscience & behavior major, is a beneficiary of the work that came before her, and is taking advantage of the opportunities afforded her. She recently earned All-American honors in two sports (track & field and soccer). Unlike Bentman, she didn’t need to arrive on campus with her cleats or worry about whether she’d have a coach or a field to play on. But across the generations, Wesleyan women share the belief that the opportunity to be a student-athlete has proven foundational for the rest of their lives.

“Wherever I go, whether it be medical school or a research job, I’m going to have to work on a team and I have the skills to navigate a lot of different types of people,” Devanny says. “I think without my teams, without these people, my college experience would just be completely different.”

Women’s Teams Inception Dates

1972 Field Hockey

1972–73 Women’s Basketball

1973–74 Women’s Squash

1973–74 Women’s Tennis

1974–75 Women’s Crew

1975 Women’s Cross Country

1975–76 Women’s Track & Field

1976 Women’s Lacrosse

1976–77 Women’s Swimming & Diving

1977–78 Women’s Hockey

1978 Women’s Soccer

1984 Volleyball

1987 Softball

2019–20 Women’s Golf

MILESTONES

1984 Kathy Keeler ’78 is the only Wesleyan graduate to win an Olympic gold medal, stroking the women’s eight crew to a top finish at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

1984 Kathy Keeler ’78 is the only Wesleyan graduate to win an Olympic gold medal, stroking the women’s eight crew to a top finish at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

1987 Allegra Burton ’87 is Wesleyan’s first woman to earn NCAA All-American honors in two sports during the same year (cross-country and track and field)

1987 Allegra Burton ’87 is Wesleyan’s first woman to earn NCAA All-American honors in two sports during the same year (cross-country and track and field)

1994 women’s soccer wins the Eastern College Athletic Conference (ECAC)—Wesleyan’s first conference championship.

1994–95 Holly Sorensen ’95 (swimming & diving) is the first NCAA individual woman champion in any sport at Wesleyan, winning the 200 butterfly and 500 freestyle titles in 1994 and the 500 freestyle title in 1995.

1994–95 Holly Sorensen ’95 (swimming & diving) is the first NCAA individual woman champion in any sport at Wesleyan, winning the 200 butterfly and 500 freestyle titles in 1994 and the 500 freestyle title in 1995.

2000 Volleyball wins the ECAC North Region Div. III Tournament.

2000 Volleyball wins the ECAC North Region Div. III Tournament.

2000-01 Women’s Crew qualifies for NCAA Championships.

2001 Volleyball qualifies for the NCAA Div. III Tournament.

2003 Jenna Flateman ’04 wins the national champion title in the 55m dash.

2004–05 Women’s Basketball qualifies for NCAA Tournament.

2018 Eudice Chong ’18 makes history, winning her fourth consecutive NCAA Singles Championship, becoming the first person (male or female) in history to win four national singles titles in any division of college tennis.

2018 Eudice Chong ’18 makes history, winning her fourth consecutive NCAA Singles Championship, becoming the first person (male or female) in history to win four national singles titles in any division of college tennis.

2018–19 Women’s Tennis becomes first women’s NCAA Champion in school history and only second team title winner (after men’s lacrosse in 2018).

2019 Ivie Uzamere ’20 wins the weight throw at the NCAA Indoor Championships, becoming the first Wesleyan athlete to win an NCAA individual championship in a field event.

2019 Ivie Uzamere ’20 wins the weight throw at the NCAA Indoor Championships, becoming the first Wesleyan athlete to win an NCAA individual championship in a field event.

For more photos from 50 Years of Title IX at Wesleyan, visit https://athletics.wesleyan.edu/galleries/womens-basketball/50-years-of-womens-basketball/988