MUSICAL SCORED BY TRASK ’89 BECOMES A BROADWAY HIT

2014_Bruce Glikas/Broadway.com

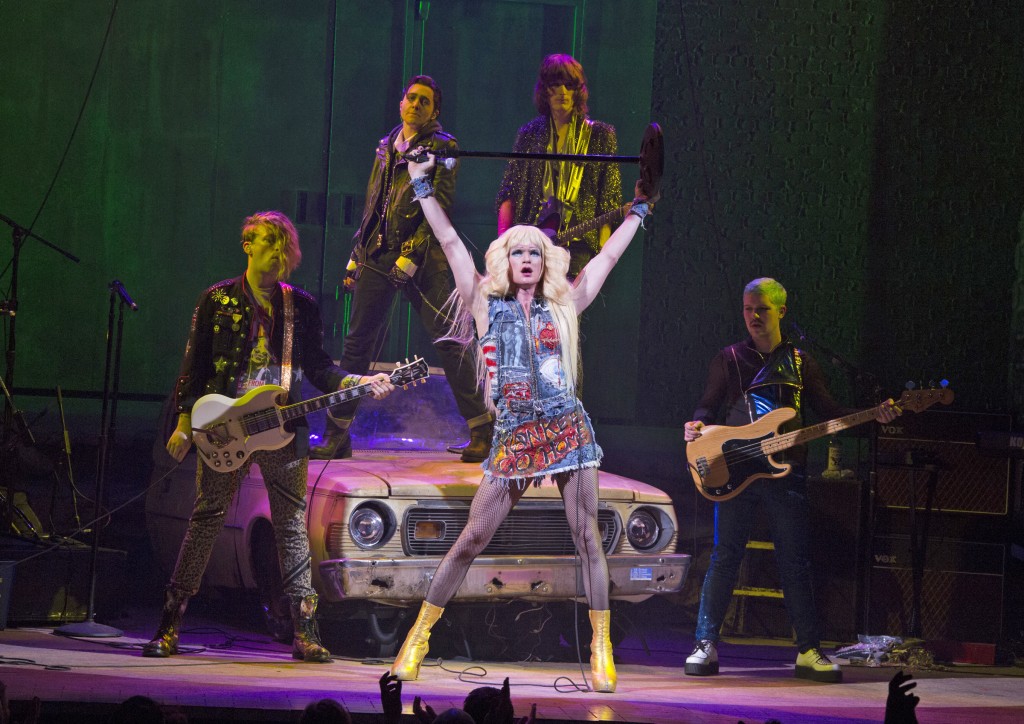

A revival of Hedwig and the Angry Inch, a rock musical with a score by Stephen Trask ’89 and a book by John Cameron Mitchell, opened at the historic Belasco Theatre on Broadway to rave reviews this past April. In June, the show received four Tony Awards, including Best Musical Revival and Best Actor in a Musical. It first opened in New York City’s West Village in 1998, where it ran for two years, and has since developed a passionate fan base, thanks to productions around the country and the world and a 2001 film version, directed and starring Mitchell, with Trask playing a band member.

In his New York Times review of the revival, Ben Brantley calls the show “one of the few unqualified pleasures of this Broadway spring.” He praises the musical numbers by Trask as being “as infectiously tuneful as anything else on Broadway now. … every one’s a crowd pleaser.”

The new production stars Neil Patrick Harris as Hedwig, in a role very different from his parts on Dougie Howser M.D. and How I Met Your Mother. Brantley writes: “With this show, Mr. Harris joins an elite club of musical-comedy male supernovas that has exactly one member these days, Hugh Jackman.”

The show is far from a typical Broadway musical material. It tells the story of a transgender punk-rock singer from East Germany named Hedwig, “an internationally ignored song stylist” who performs with a band called the Angry Inch, whose name refers to Hedwig’s butchered appendage from a botched sex change operation. The audience watches Hedwig’s musical act as she sings about her past as an army bride brought to America and abandoned by her soldier husband, the development of her songwriting talent, and her relationship with Tommy Gnosis, a successful teen idol with whom she wrote songs and who then left her. During the course of the riveting, often funny 90-minute memoir, Hedwig dons some fabulous outfits and amazing wigs.

Trask recently shared some memories of the musical’s beginning. Around the beginning of 1994, he and Mitchell started working on musical based on Mitchell’s life growing up as the son of a military officer. Originally, the main character of the project was Tommy Gnosis, a general’s son. But then Mitchell told Trask a story about Helga, who had been his babysitter, a German army wife and divorcee who was also a prostitute on the side.

“I thought this was a fascinating woman; let’s make her into a character who sings,” Trask says. “It was my idea to base the show on somebody he knew. The two of us just added different elements together, some right there in the moment and some later, ideas that grew over time.”

One inspiration for the show came from Plato’s Symposium, which deals with the genesis, purpose, and nature of love. Mitchell showed Trask the story, which inspired him to write “The Origin of Love,” a highlight of the score.

A turning point for the show occurred when Mitchell performed a 30-minute version of the show at a downtown Manhattan club, SqueezeBox!, where Trask was working as a musical director of the house band. The club was a place where drag and transgender entertainers felt comfortable and found their voices. Mitchell, who hadn’t done drag before, performed cover tunes and one original song, “The Origin of Love.” The act was well-received there.

Over the course of four years, Trask continued to write more songs for Hedwig, who gradually became the main character. Trask and Mitchell continued to develop the show as sort of a cabaret act by booking gigs at nightclubs, rock clubs, and other venues.

“We did a comic gig at a music venue and performed in burger and beer joints,” Trask says. “We did a gig on somebody’s patio for an AIDS fundraiser. We did one performance at the Public Theater, but they would only give us one night.”

According to Mitchell in a recent Rolling Stone interview, “Other theaters where we were dying to do it were just not interested. We were just too weird and downtown and drag and rock and roll.”

Then the experienced director Peter Askin was brought in.

“Askin helped take essentially a very dramatic nightclub act, a one-act show, and showed us how to turn it into a full evening of theater,” Trask says. “He restructured our work to give it a different dramatic through line. He suggested that the sex change operation needed to come at the end of act one and that Tommy Gnosis needed to appear at the end of show. In doing so, we were able to find the spots for the rest of the songs and the rest of the monologue..”

With a small workshop production at Westbeth in the West Village, the show was about 85 percent finished and then Askin decided they were going to need to find a theater of their own.

The show finally found a home at the Jane Street Theater, an off-the-beaten path location near the West Side Highway in the West Village, near the Meatpacking District.

“The theater was in a derelict space, in a flophouse hotel that had a present and a past,” Trask says. “The present hotel was a single-room-occupancy flophouse that catered mostly to people picking up prostitutes, junkies, and backpackers who used it like a youth hostel. In the past, the building had been a sailors’ hotel, where cruise ships used to put up their personnel when they were docking. And when the survivors of the Titanic were brought to New York, they all stayed at the Jane Street.”

Hedwig and the Angry Inch has had a tradition of incorporating whatever space it lands in, and the printed script has an author’s note encouraging people to take that approach when doing the show. The show took off at the Jane Street Theater, a venue that had a history and personality particularly well-suited to the play’s material.

Hedwig opened on Valentine’s Day 1998 to mixed reviews but also some raves, including one in The Wall Street Journal and another in The New York Times by Peter Marks, who called it “an adult, thought-provoking musical about the quest for individuality, the attempt to forge an identity that works for both the head and heart. And it is terrifically served by a fresh and tuneful score by Stephen Trask, who meets the difficult challenge of creating rock-, folk- and country-influenced songs that help tell a story.”

Despite those enthusiastic reviews and positive reaction from audiences, Trask recalls that early in the run, the show had trouble catching on.

“Theatergoers who wanted to spend the money on tickets, although our tickets were cheap at the beginning, didn’t want to come to this neighborhood to hear rock and roll. And rock fans really didn’t have a desire to come see theater, and gay people didn’t want to hear rock music. So it was difficult to find the right audience for this show.”

The show struggled for about three months but then the critic from Time magazine said the show had “the most exciting rock score written for the theater … ever” and named it the Best Musical of 1998.

That review radically changed the show’s profile and helped sell tickets, and Hollywood, rock and roll, and theater celebrities started coming to see it, including Lou Reed, Barry Manilow, Davie Bowie, Glenn Close, Patti LuPone, Mike Nichols, and Robert Altman. Rolling Stone did a profile, calling the show “the best rock musical ever.” Peter Marks from the Times came back to see the show in July 1998 when John Cameron Mitchell went on leave for a few weeks, and respected musical theater star Michael Cerveris who previously starred in The Who’s Tommy, took over the role. Marks once again loved the show and called it a “downtown phenomenon” and added that “Cerveris … embodies the shape and spirit of Hedwig Schmidt as convincingly as the role’s originator.”

Cerveris showed that Hedwig could be played well by other actors besides Mitchell, who was so closely associated with the part.

Since it played off-Broadway, Hedwig and the Angry Inch has spawned successful productions across America and around the world in all shapes and sizes. These productions adapt themselves to the theater space at hand, staged by those who care a great deal about the material. A production in Japan has played for many years, and South Korea even hosted a popular televised reality show about the search for a new star to play Hedwig. Over the years, the musical developed a devoted following.

In an interview on Playbill.com, Trask explains the show’s special attraction:

“Hedwig is a very unusual person. … And yet, over the course of the evening, the stories that Hedwig tells and the emotions she expresses through the songs are things that people can really identify with. And so any time that you’re brought to a place where you can identify with someone who is so unlike you, it’s hard not to then change within yourself.”

When the show was still playing off-Broadway, a move to Broadway was considered but the material didn’t seem likely to work on Broadway where rock music wasn’t all that popular. But around five years ago, producer David Binder, Trask, and Mitchell began to reconsider bringing the show to Broadway, where ticket buyers’ tastes had begun to change. With successful productions such as Rent, The Who’s Tommy, and American Idiot on Broadway, rock music was no longer a drawback, and successful musicals such as La Cage aux Folles and Kinky Boots had made characters in drag more audience-friendly. And this past fall, two Shakepeare plays on Broadway imported from the Old Globe Theatre in London were a huge success and featured all-male cast with men playing women in women’s clothing. Those plays happened to play in the Belasco Theatre, where Hedwig is now ensconced.

“I think that our culture has moved in a direction that allows something of this style of show to have a mainstream appeal,” Trask says. “Drag is certainly not shocking. People are more open to transgendered people than they used to be. It’s cool people are willing to hear rock music on Broadway—but it’s still not the norm. So you put all of this together and it feels new, but you’re not so ahead of the moment that you’re struggling to pay weekly operating expenses.”

Mitchell, who had begun directing films, wasn’t interested in reprising the role. The producers and creators then thought Neil Patrick Harris, star of How I Met Your Mother, would be perfect for the role. Harris, an openly gay actor, had already done a few stage musicals and proved himself a wonderful host and entertainer on the Tony Awards with a natural rapport the audience, just as Hedwig plays a host of her own concert in the show. Harris initially wasn’t sure he was right for the part but eventually was persuaded. The production’s creative team had to wait several years until his commitment to his popular television series was done.

Harris’s celebrity name on the marquee helps to attract a wider audience than those who already familiar the show. The musical set a box office record at the Belasco Theatre in May and June. The producers announced in July that that the show had recouped its capitalization, which was about $5 million. The production will continue its run when Harris leaves the show in August with Andrew Rannells (The Book of Mormon and TV’s The New Normal) taking over the lead.

Taking the show to a Broadway theater has required some adjustments but not radical ones.

“The goal is to make changes without anyone really noticing,” Trask says. “Like blowing up a picture so it is bigger by just the right amount.”

To make use of the larger setting, book writer Mitchell incorporates the idea that Hedwig has been given access to the Belasco Theatre for a one-night-only gig because its previous tenant, Hurt Locker: The Musical has closed abruptly. This conceit allows Hedwig to perform on the set of that musical, which depicts a war-torn city landscape. The set has been designed so it also suits Hedwig’s performance; a damaged wall that looks like it was hit by a bomb lowers the proscenium to create a more intimate space. The back wall is brought forward to lower the depth of the stage. A damaged car in the middle of the stage allows a space where Hedwig can tell her stories.

As he did in the off-Broadway production, Trask serves as the orchestrator for the revival, and changes have been made to the score.

“Every song has some kind of change,” Trask says. “Most of the parts, such as those for bass and drums, are different. Sometimes it’s just finding things that worked in the movie version, things that worked in the stage show, and finding ways of combining them. Sometimes it’s being inspired by cover songs that we’ve heard and trying to figure out how to incorporate what we’ve heard in a cover version.”

“Everybody in the band sings and is a multi-instrumentalist so the vocal arrangements are bigger with six people,” he adds. “There are times when there used to just be a solo instrument, and now there’s a percussion pattern and the bass player is playing the keyboard patch. We also brought in large floor toms so the drums can sound bigger, sometimes more orchestral. New textures are also available to us, and we bring in some 12-string guitar here and there. So it’s all bigger but just the right amount and true to what the original intent was.”

Neil Patrick Harris has to carry the show for 90 minutes, and theater critics and audiences are energized and seduced by his performance.

Ben Brantley in the Times writes: “Mr. Harris has much more than marquee and recognition value. He also has a master entertainer’s gift for making the rough go down smoothly. And what might be distasteful from other mouths—including raunchy double entendres that deserve (and receive) rimshots—sounds delicious coming from his. From the moment his Hedwig makes her David Bowie-esque entrance, we’re his to do what he will.”

According to Trask, Mitchell, who originated playing Hedwig, always wanted to be a rock performer.

“I don’t think that was something that Neil always wanted to do. It was something he learned how to do,” Trask says. “Neil learned a body language, how to be a rock performer—studying Iggy Pop, the Ramones, the Clash, Lene Lovich, Devo, Talking Heads, and Tina Turner—and seeing different ways they might hold their body or address the crowd. He put together his own vocabulary, getting an understanding of the physical and emotional relationship between the crowd and the performer and the microphone and the performer—and doing it all on heels. He did a lot of work with the choreographer.”

Hedwig isn’t the only Broadway show Trask has worked on this season. He also was hired to co-orchestrate the large-scale production of Rocky, a musical based on the popular film, with a score by Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens.

“It was unexpected for me to be asked to do that,” Trask says. “They brought me in because the style of the orchestrations that preceded me on most songs sounded extremely Broadway, which is fine—but the show doesn’t look or feel like a glitzy Broadway show. They needed orchestrations that sounded like what the rest of the show felt like. I got to bring things that I’ve learned from doing films. It was a good way to prepare myself for Hedwig, to do something on that scale in a Broadway house.

“It was a real treat to get inside the brain of a different composer,” he adds. “That’s basically what it was and there was definitely like a great deal of camaraderie. It’s fun to be involved in other people’s projects because everything can’t just be me, me, me. I would certainly like to do something like that again.”

Outside of Hedwig, Trask also is a sought-after film composer. He has written scores for films such as Dreamgirls, The Station Agent, The Savages, and The Back-Up Plan, and several films directed by Wesleyan alumnus Paul Weitz ’88, including In Good Company, Little Fockers, and Admission.

“Being a songwriter can be very solipsistic.” Trask says. “When I’m working a on a film, I’m writing for the director and the editor. I enjoy the back and forth with other people. It’s the same if you work with a band.”

Trask also continues to work on stage musicals, including two projects with Peter Yanowitz, a songwriter who is currently the drummer in the Broadway Hedwig band, and with Rick Elice, who wrote the books for Jersey Boys, The Addams Family, and Peter and the Starcatcher. And for Hedwig fans, a sequel written by Trask and Mitchell may come to light someday.