OPENING DOORS TO HIGHER EDUCATION

Growing up in his grandmother’s house in Harer, Ethiopia, Nebiyu Daniel barely attended school. Though he spoke no English upon arriving in the United States at the age of 10, by 13 he was proficient enough that he started to dream of attending college—something no one in his family had done before.

Growing up in his grandmother’s house in Harer, Ethiopia, Nebiyu Daniel barely attended school. Though he spoke no English upon arriving in the United States at the age of 10, by 13 he was proficient enough that he started to dream of attending college—something no one in his family had done before.

“For most of high school, I performed at a high level, but I had always thought that I would attend a local university at best, and if not, I would begin at a community college as many from my high school did. I always assumed that going to college out of state was for the rich kids or those who came from private school,” he said. “The option of going to a highly selective college was a dream that I had in my heart but always thought was impossible, so I never told anyone I wanted to attend these schools.”

In fact, most low-income students with high grades and test scores never apply to the nation’s best colleges, assuming such schools are out of reach financially. These students are often unaware of the financial aid available or simply don’t consider these schools because they’ve never met anyone who attended one. Many choose instead to attend community colleges or state schools close to home. Only 34 percent of high-achieving seniors in the bottom fourth of the income distribution attend any of the nation’s 238 most selective colleges, compared to 78 percent in the highest income quartile, according to a 2013 study by Caroline M. Hoxby of Stanford University and Christopher Avery of Harvard University. The effects of this disparity reverberate throughout society over time, as those who attend elite institutions go on to earn substantially higher incomes over their lifetimes. More-selective colleges also have significantly higher graduation rates than their less-selective counterparts.

Wesleyan, like many of its peer institutions, has been working for decades to open up higher education to populations of students who never imagined themselves going to college—or at least not to an elite school like Wesleyan with a price tag that likely surpasses their family’s annual income. Once home to a student body of only white men mostly from well-to-do families, in 1965, under the leadership of Dean of Admission Jack Hoy, Wesleyan began actively recruiting minority students, admitting one Puerto Rican student and 13 black students to the Vanguard Class of 1969. By 1970, blacks and other minorities constituted 12 percent of the overall student body and 20 percent of the freshman class, putting Wesleyan far ahead of many other colleges and universities in this regard.

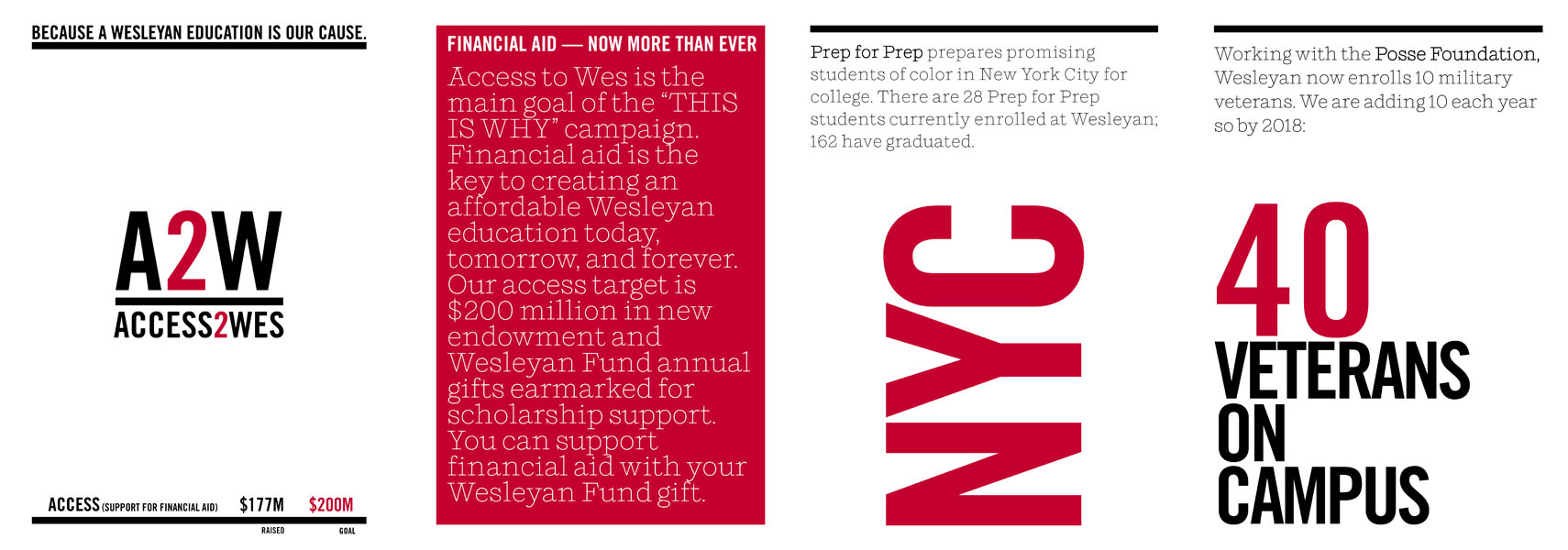

Since then, Wesleyan has continued to expand access through a variety of different recruiting and affordability initiatives, and partnerships, and is currently pursuing a $400 million fundraising campaign, of which $200 million will go to support financial aid with the goal of increasing access. Today, the Office of Admission works with hundreds of individual community-based organizations (neighborhood, state, and national) to identify and recruit talented students who likely would not find Wesleyan on their own. These organizations offer a variety of services to high schoolers, from supplemental writing instruction and academic summer boot camps to assistance with the college search and application process. All serve as a pipeline for colleges like Wesleyan to recruit high-achieving students who may be from low-income families, underresourced schools, or communities with a poor track record of college attendance.

One partner organization is A Better Chance: Wesleyan is second only to Columbia in the number of talented students of color it enrolls through ABC, and President Michael Roth was honored by the organization with the 2014 Benjamin E. Mays Award in recognition of Wesleyan’s efforts to diversify higher education. Another partner is QuestBridge, which over the past five years has brought to Wesleyan 177 low-income and first-generation students. And through Prep for Prep, Wesleyan has enrolled nearly 200 of the most promising students of color from New York City—more than any other school except Harvard.

One partner organization is A Better Chance: Wesleyan is second only to Columbia in the number of talented students of color it enrolls through ABC, and President Michael Roth was honored by the organization with the 2014 Benjamin E. Mays Award in recognition of Wesleyan’s efforts to diversify higher education. Another partner is QuestBridge, which over the past five years has brought to Wesleyan 177 low-income and first-generation students. And through Prep for Prep, Wesleyan has enrolled nearly 200 of the most promising students of color from New York City—more than any other school except Harvard.

Wesleyan’s newest partnership is with the Posse Veteran Scholars Program, which places talented military veterans at top-tier colleges and universities, where they receive four-year scholarships. Wesleyan, only the second school after Vassar to sign on, plans to enroll a new “posse” of 10 veterans each year, ultimately having 40 vets on campus at any time. (Read more about the program and meet two Posse veteran scholars in the sidebar.)

Today, Nebiyu Daniel is a member of the class of 2018 at Wesleyan with plans to pursue a biology or molecular biology and biochemistry major, and perhaps a second major in philosophy. He arrived at Wesleyan with the help of an organization called Leadership Enterprise for a Diverse America. One of 60 students admitted to LEDA, he spent a summer at Princeton University, where he received leadership training, writing instruction, standardized test preparation, and college guidance. It was through LEDA that Daniel learned about Wesleyan.

“I saw myself in a large research institute studying the sciences. A small liberal arts college was not a place for me. When we came to visit Wesleyan with LEDA, I was in love with the campus. I started to see all the things this small liberal arts school had to offer and I knew this was the one school I wanted to attend. Going into the labs and seeing how many of the undergraduate students were doing research blew my mind. I saw myself someday standing in one of those lab coats.”

The summer before entering his first year at Wesleyan, Daniel participated in the Wesleyan Math and Science Scholars (WesMASS) program, where he received mentorship from faculty while getting a preview of some of the research being done on campus. “I partook in small intensive mini-courses that gave me a glimpse of what it meant to be a student at Wes,” he said.

From an early age, Morgan Scribner ’16 of Little Rock, Ark., was taught to value education. While she worked hard in school so she could go on to college, she never pictured herself at a place like Wesleyan. She sought assistance in the Arkansas Commitment program, which helps students improve their ACT scores, maintain good GPAs, attend college symposiums, tour colleges, and work through the application process.

“The program’s aim was to help minority students understand that there is more to college than state schools and HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities),” Scribner explained. The students were encouraged to apply to private liberal arts colleges and universities.

Scribner first learned of Wesleyan as a high school junior, when she met Associate Dean of Admission Clifford Thornton at a college symposium. He encouraged her to consider Wesleyan.

“I listened to his spiel, and my initial reaction was, ‘Walk away from this table, you’re from Arkansas,’” said Scribner. The following year, she encountered Thornton again at a symposium. Though Scribner was focused on finding a school that would train her for a career in the music business, Thornton promised to fly her out to Wesleyan if she applied and was accepted. Finally, she decided to apply to Wesleyan, but remained ambivalent about the school until she attended WesFest and “realized that there was more for me than any state school or HBCU had to offer. I knew I wouldn’t be afforded the same opportunities, so I had to take advantage of the situation.”

In her role recruiting students in Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, and South Carolina, Assistant Dean of Admission Sydney Lewis commonly runs into this type of resistance. Talking to high school students, she finds many who have written off traveling far away for school or who are intent on finding a school with a strong program in, say, nursing or criminal justice. The concept of a liberal arts education is foreign to a large percentage of the students she speaks with. Rather than pursue highly specific training in one field, Lewis encourages kids to think ahead.

“I tell them, ‘Demographers say that people in our generation will have an average of four careers in their lifetime, and a lot of those careers don’t exist yet. How can you prepare yourself right now for a career that doesn’t exist yet?’” Lewis said. “The way to make yourself the most marketable is to develop a robust skill set and explore lots of areas, so in 20 years you’re prepared to move fluidly into the next field. No matter what you do, having excellent critical thinking skills will make you the most desirable candidate for any kind of job or graduate school.”

Though she now speaks eloquently about the benefits of a Wesleyan education, only a few years ago, Lewis was on the other side of the table. As a high-achieving student in a medium-sized inner-city public high school in Atlanta, Ga., and the daughter of two public school teachers, money was always tight in Lewis’ family. Her father strongly encouraged her to attend a Georgia state school, where she would qualify for a full scholarship thanks to the HOPE program geared toward students with high GPAs. But her mother, who grew up in New York and attended an elite college, urged Lewis to explore all her options. Through Internet research, her mother found QuestBridge, an organization that brings talented low-income and first-generation students to elite colleges.

Lewis first applied to QuestBridge’s College Prep Scholarship program at the start of her junior year. She was accepted and was provided with a laptop, an online SAT prep course, and travel expenses to attend a college conference at Yale University.

“For a long time, I was bound and determined to go to Yale. Coming from the South, I knew about Georgia state schools and the big football schools my friends went to, and then I had heard of Yale. In my mind, there was nothing in between,” Lewis said.

Yet when she got to Yale, she said, “it felt wrong to me.” She met Associate Dean of Admission Chris Lanser at the conference, who encouraged her to visit Wesleyan. On campus, “people were so happy to talk to me and my mom,” said Lewis. She applied in the second early decision round and was accepted into the Class of 2014.

For Lewis, QuestBridge was critical in helping her discover and choose Wesleyan.

“In many public schools, counselors have huge caseloads and are not well-informed about schools outside their geographic area,” said Lewis. “We were lucky to find QuestBridge. They helped me to think outside the Ivy League and pointed me toward great schools that were able to provide sufficient financial aid to make college possible for me.”

Financial aid is, of course, an essential part of making Wesleyan accessible. Wesleyan meets the full demonstrated financial need of students who enroll. For most families who earn less than $60,000, that means a financial aid package without loans. For families earning more than $60,000, students are asked to borrow no more than $19,000 over the course of their entire undergraduate career.

John Gudvangen, associate dean of admission and financial aid and director of financial aid, pointed to other provisions that make applying to and attending Wesleyan more affordable: certain application fees are waived for low-income families; students are allowed to charge books on their accounts at the bookstore, and may use outside scholarship funds to cover the cost of the university’s health insurance policy. Wesleyan also has committed to capping tuition increases to the rate of inflation. And the school offers a “three-year option,” which allows students to graduate early, saving approximately 20 percent off the total cost of a Wesleyan education.

In addition, beginning this fall, applicants are no longer required to submit SAT or ACT scores. As Dean of Admission and Financial Aid Nancy Hargrave Meislahn told Bloomberg Businessweek in October, “This is a moment in time where we felt [there are] growing questions in K–12 and beyond about the value of standardized testing… We also see this as an access initiative. We’ve known for a long time the correlation between test scores and income.”

Improving access and equity in education is a passion of Lewis’, and one that developed over her four years as a Wesleyan student. Though she came to Wesleyan intending to pursue a premed path, her First-Year Initiative class, Poverty in the U.S., captured her attention. The in-depth research project she completed for this course on the correlation between poverty and early developmental delays remained of interest throughout her academic career at Wesleyan, and ultimately led to her thesis, titled, “A Tale of Two Turnarounds: Corporate Ideology, Community Organizing, and the Hidden Curriculum of Whole School Reform.” She received high honors.

Outside the classroom, Lewis led a student group, Wesleyan Students for Just Education; worked as an AmeriCorps volunteer, offering tutoring and teacher support at Macdonough School; and co-founded and taught at Kindergarten Kickstart, an intensive summer program led by Wesleyan faculty and students to help underprivileged Middletown children prepare for kindergarten.

Though she eventually would like to teach or work in educational policy, Lewis was happy for the opportunity to work for Wesleyan’s Admission Office after graduation and help spread the word about Wesleyan to other high school students in the South. Knowing from her own experience how many public school guidance counselors were entirely unfamiliar with Wesleyan and other schools outside the region, Lewis spends much of her time traveling to schools and meeting with guidance counselors. “I try to get them excited about Wes so they can think about which of their students might be a great fit,” she said.

Fifty years after the Vanguard Class entered Wesleyan, the sum of these efforts to increase access is apparent on campus. This fall, Wesleyan appeared on The New York Times’ list of the most economically diverse colleges, which judged schools on the share of freshmen in recent years who came from low-income families, and the net price of attendance for low- and middle-income families. Given the size of its endowment, Wesleyan’s commitment to economic diversity in its student body—based on enrollment of Pell Grant recipients—is relatively strong, the Timesfound. And listening to students here, it’s clear that they are passionate about keeping Wesleyan open and accessible to students from all walks of life. For someone like Daniel, who, growing up, never imagined himself at a place like Wesleyan, that passionate commitment means he has found the university to be a warm and welcoming environment.

“I have found comfort in my surroundings here and learned to embrace everything Wes. The student community is beyond tremendous. The cognitively diverse minds that are on this campus are truly astounding,” he said. “I have met people from all around the world and I’m learning a lot more about myself through this community than I ever imagined.”

FROM THE MILITARY TO THE CLASSROOM: POSSE BRINGS VETERANS TO WESLEYAN

Michael Smith and Kyle Foley were riding the bus home together when they got the good news: acceptances to Wesleyan. They come from very different backgrounds but share one important experience: both served their country in the military. And with that fateful phone call, they, together with eight other veterans, are now members of Wesleyan’s Class of 2018 and the inaugural “posse” of veterans at Wesleyan.

Through its partnership with the Posse Veteran Scholars Program, announced in fall 2013, Wesleyan aims to dramatically increase its enrollment of veterans. According to the Posse Foundation, there are more than 2 million post-9/11 veterans currently eligible for the Yellow Ribbon Program and for GI Bill tuition benefits in the United States, but few find their way to the most selective colleges and universities. Posse’s program identifies talented veterans who are interested in pursuing bachelor’s degrees and, with full scholarships, could succeed at a top-tier institution. Wesleyan is only the second school to partner with Posse after Vassar, and enrolled its first group of 10 veterans this fall, with plans to enroll a posse of 10 each year.

Smith, raised in Chicago, graduated from high school and worked in food service for a time before joining the Marine Corps. Always a shy person, Smith says he developed a sense of confidence in the military.

“Early on, Marines are taught how to lead. You’re given responsibilities that, in civilian life, you might think are well above your capabilities, but the idea is to pull you up,” Smith said.

After leaving the Marines in 2007, Smith worked at a few banking jobs and as a military recruiter. Eventually, he decided to enroll at Bunker Hill Community College in Charlestown, Mass., in 2012. In summer 2013, he attended the Warrior-Scholar Project at Yale, which helps veterans transition from the battlefield to the classroom. It was there that he learned about Posse.

Foley, who grew up in the Boston area, had three years of college at Hamline University in Minnesota under her belt before joining the military. Majoring in history and theology, she grew skeptical about her future job prospects. She decided to drop out and join the Navy, where she worked as a construction mechanic in the Naval Expeditionary Combat Command. She served two tours in Afghanistan, and re-enlisted as a combat life-saver. Though Foley had imagined spending her whole career in the military, after six years she found her options were limited.

“When I got out, it became apparent very quickly that I couldn’t rely just on my military training. The way the military certifies you as a medic, there isn’t a civilian equivalent,” she explained. She enrolled at Bunker Hill with plans to transfer eventually to the University of Massachusetts-Boston. But she performed so well at community college that she decided to set her sights higher. She came across an ad for Posse on the Internet.

“I kept thinking, this seemed too good to be true,” she said. She didn’t fully believe it until she was accepted by Wesleyan.

“I feel like Wesleyan is a good school no matter what you’re studying. I already have technical training, but in Wesleyan, I’m looking for a little more depth and breadth. There aren’t requirements here, so you can explore what you’re interested in,” she said. “I think that’s important when you’re a young person.”

Her first semester, Foley is taking courses in neuroscience, American constitutional order, and Hebrew.

The Posse members meet weekly as a group with their adviser, Andy Szegedy-Maszak, the Jane A. Seney Professor of Greek, and each individual also has a weekly one-on-one session with Szegedy-Maszak.

“We’re very open with each other and can be honest—sometimes blunt—with each other.” Smith said of the group. “It feels like a safe space to do that. Folks around campus can probably tell that we enjoy each other’s company. But we also mingle with the wider community.”

Smith is thinking about joining a musical group next year and perhaps the rugby team.

“I came here with my heart set on studying economics, but this is Wesleyan, and you don’t need to have your heart set on anything. Since being here, my passion in music has been reinvigorated, and that’s something I want to further develop.”

Both Foley and Smith say it has been a process to adjust to life at Wesleyan.

“Wesleyan is a much more challenging academic experience than I’ve had in my entire life,” said Smith. “I’ve had to figure out a routine, time management, and good work habits.”

For Foley, the most important skills the military equipped her with are “discipline and consistency.”

“The military also encourages you to speak up when you don’t know what you’re doing, because that’s not something you can cover up,” she said. “At Wesleyan, it behooves you to ask professors for help when you need it. The professors here appreciate that and are always really helpful.”

As an older student, said Smith, “I’ve had some profound failures in life, but they’ve given me perspective. I realize that if something happens that feels devastating, as long as I’m willing to reach out to the right people and receive sound advice, I’ll get back up. No one else in my family has attended an institution of Wesleyan’s caliber. I feel like I have a responsibility to take full advantage of it; to give myself to the experience and see what comes out on the other side.”

For more information on the Posse Veteran Scholars Program, contact Antonio Farias, chief diversity officer, at afarias@wesleyan.edu.