A MUSICAL REVOLUTION ON BROADWAY

Composer, book writer, and actor Lin-Manuel Miranda ’02 and director Thomas Kail ’99 have reunited to collaborate on Broadway with Hamilton, hailed by critics as one of the most original American musicals in years.

In 2007, Wesleyan magazine published an article about a groundbreaking new off-Broadway musical In the Heights, the first major show by a young composer Lin-Manuel Miranda ’02 and directed by Thomas Kail ’99. This show about the lives and loves of the residents of block in the Latino neighborhood of Washington Heights introduced a fresh musical voice reflecting influences of traditional Broadway, salsa, merengue, and hip-hop, and was one of the few musicals in American musical theater history to focus on Latin American life. In the Heights was both a popular and critical success when it moved to Broadway in 2008, winning the Tony Award for best musical, as well as Tony Awards for Miranda and co-orchestrator Bill Sherman ’02, and running on Broadway for several years.

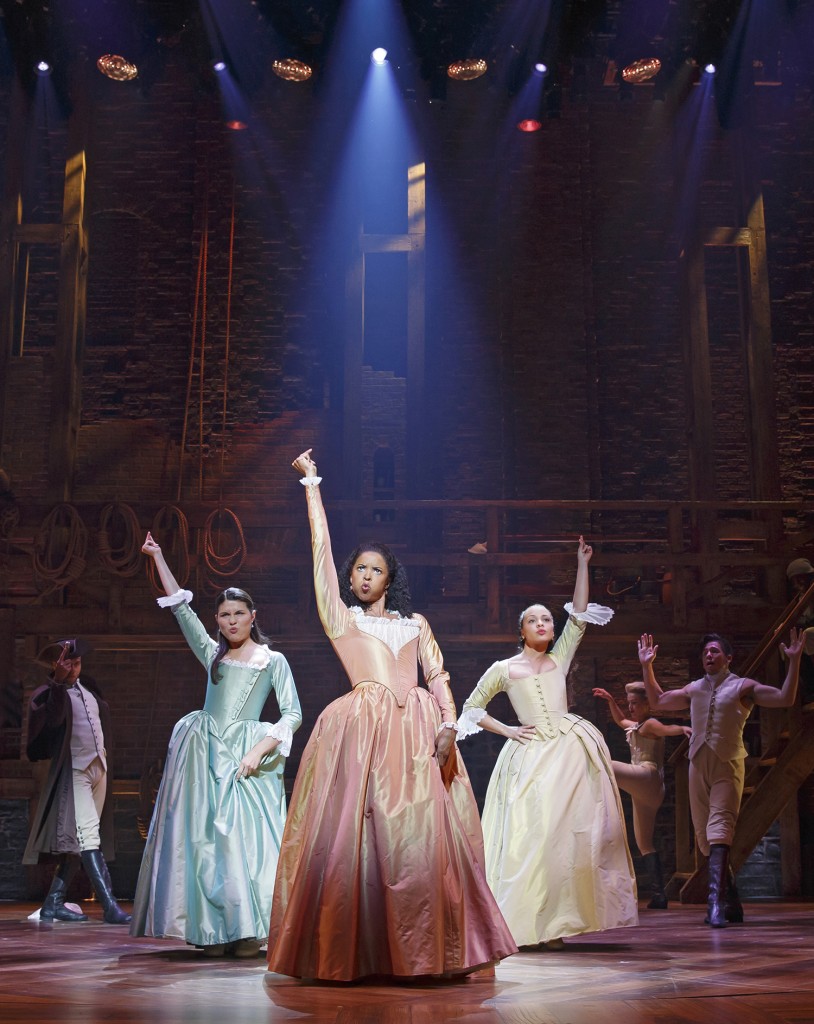

Now Miranda and Kail are back on Broadway at the Richard Rodgers Theater, with Hamilton, a musical inspired by Ron Chernow’s acclaimed biography, Alexander Hamilton, about a poor immigrant who came to New York and became one of America’s Founding Fathers and U.S. Treasury Secretary. The production received rave reviews when it opened, with high praise for Miranda’s bold, inspired book and score and superb performance in the title role, and Kail’s masterful direction. Hamilton reimagines early American history through dynamic hip-hop and more traditional musical theater songs, sung by a stellar cast of mostly non-white actors representing the revolutionary Founding Fathers.

The show moved to Broadway last summer, with an advance sale of $27.6 million, and was covered extensively by the national media, with Hollywood Reporter calling it “a cultural phenomenon and an instant milestone in the art form.” It has now become one of the hottest tickets in town, sold out until next summer, and Miranda recently received a MacArthur “genius” fellowship. Peter Marks in The Washington Post wrote: “A great musical, Hamilton … is a captivating mirror of a man whose life it surveys: blazingly original, restlessly innovative, magnetic from start to finish.”

Miranda and Kail recently talked to Wesleyan magazine about their creative work on the musical.

David Low: The initial inspiration for Hamilton was the acclaimed Ron Chernow biography Alexander Hamilton, which you started reading while vacationing in Mexico. What about the book inspired you to start writing hip-hop songs about Hamilton?

Lin-Manuel Miranda: It was one of those lightning bolt moments. I knew just about as much as anybody else when I started reading it. I knew he was one of the Founding Fathers and was shot in a duel. I didn’t know he was an immigrant, and I didn’t know about his Dickensian traumatic early childhood. The first few chapters of Chernow’s book read like a suspense novel. How did this kid get from his beginnings [Hamilton was an orphan, born out of wedlock] to become a Founding Father? When I got to the part where he wrote a poem and that helped him leave the island of St. Croix, I thought well, “This is a hip-hop story.” This is someone who wrote himself out of circumstances through verse. [According to Chernow, after reading Hamilton’s writing, local St. Croix businessmen raised money to send Hamilton to North America to be educated.]

DL: You first performed a song about Hamilton at the White House in 2009. What gave you the courage to do that?

LMM: It felt like a sign to me. How often does the White House call and ask you to perform? Almost never—this is not an everyday occurrence for anyone. It was their first evening of poetry and spoken word and I had these 16 bars of a Hamilton song that I had been working on—it just felt like a sign. What a great way to keep the tires on this thing, in the cradle of American democracy—the President’s house. The “ask” felt like a sign to try this out, which was riskier than doing something tested and proven from In the Heights. I performed what became the opening number of the show, “Alexander Hamilton.” It was the only song that I had finished at that point. It was me condensing the first two chapters of the book into one song.

DL: You then wrote a group of songs called The Hamilton Mixtape and that was going to be a concept album.

LMM: I took my cue from Andrew Lloyd Webber, whose Jesus Christ Superstar was a concept album first. Write an album, make a bunch of kickass songs about Hamilton, and then let someone else stage it. That notion actually turned out to be a blessing because there is as much lyrical density in the songs as in my favorite hip-hop songs. They were made to bear more fruit upon repeated listening. I don’t think I would have packed the ingredients that tightly had I just been worrying about it being a stage piece and getting everything the first time. Because I was thinking that people would be listening to the songs more than once, I was able to pack them full of allusion, alliteration, double entendre, and all the fun stuff my favorite rappers get to do when they write.

DL: When did you know that The Hamilton Mixtape was going to be a full production?

Thomas Kail: January 11, 2012 at an American Songbook concert at Lincoln Center. That was the first time we really put it on in front of people and watching the reaction, I knew 20 seconds into that. When we did that concert we walked out of it knowing that there was life on stage that could be electric. In whatever form it took, whether it followed a traditional storyline, whether it was linear or nonlinear, we knew that it would live on stage.

LMM: American Songbook represented a highlight reel of Alexander Hamilton’s life, or at least as much as I could write between the six months between saying yes to the concert and our date, January 11, Hamilton’s birthday. A lot of those songs survived in the current show in some form. “Helpless” where he meets his wife. “Right Hand Man” when he starts working for Washington. We had early versions of the “Cabinet Battles.” We had the Maria Reynolds affair song, “Say No to This.” We had a song that didn’t make the show called “Valley Forge.” And we also had, “My Shot” and the aforementioned “Alexander Hamilton.”

DL: When you started hearing Lin’s songs for Hamilton, what did you find particularly compelling about the project?

TK: Lin discovered a subject matter that allowed his particular skill, the density and complexity of his lyrics, and the emotionality of his music to be fully accessed. It felt like an ideal match. We were both unwavering in our belief that there was a story that deserved to be told and that the way that Lin was approaching the storytelling was valid and thrilling—and that just grew the more music he created.

DL: Working on the book, how did you decide which historical figures to concentrate on for the show?

LMM: The challenge of presenting Hamilton’s life is that there are so many incidents, you really have to pick and choose what you are going to present dramatically and have momentum. Because someone could write an entirely different musical about Hamilton, use none of the incidents I used, and still have a pretty good show because he’s done so much. That’s the fun of having a subject like that; there’s a wealth of information and story and you have got to find the through line within it.

Hamilton becomes the through line. He’s our way into American history. The most important characters are the ones that intersect with him the most. So you see his friend John Laurens in Act 1 and Hercules Mulligan, an early Hamilton supporter who was a successful tailor and merchant. There are other important figures that we just don’t have time for. People ask me about Ben Franklin but he doesn’t make it into the show because he did not interact with Hamilton that often. They were bedfellows at the Constitutional Convention and that was about it. John Adams is depicted as an off-stage character because the momentum of the show was going so fast by Act II.

DL: In terms of hip-hop music, what specific hip-hop artists have influenced or inspired you? Some of them are referenced in some of the songs in Hamilton.

LMM: I’m pulling from everything I know in my hip-hop vernacular, having grown up with a lifetime of it. It was interesting working recently with Questlove of the Roots who was a working artist in the same era as many of the artists I’m referencing. The Roots got signed in the early ’90s. Most of the hip-hop references in my show are ’90s hip-hop. And also East Coast hip-hop. I was very conscious of this show as a love-letter to New York. So there are more Biggie references than Tupac references because I was drawing on the east coast New York-based hip-hop I grew up with as a teenager. So Mobb Deep, The Notorious B.I.G., DMX, these are all the rappers that I drew on when figuring out Hamilton’s language. What I really love, and this speaks to the Stephen Sondheim word nerd in me as well, I love the polysyllabic rappers.

There are lots of different types of hip-hop delivery systems. The ones I love the most are the ones packed with internal rhyme and assonance just the way I nerd out when Sondheim goes, “While her withers wither with her” [lyric from Into the Woods] or “Then you career from career to career” [lyric from Follies]. I so enjoy that wordplay, internal rhyme, and assonance as a marker of a character’s intelligence and wit. Hamilton is a polysyllabic monster and that’s why his songs take so long to write. And Angelica Schuyler as well, being his intellectual equal, has as much lyrical density as any of the Founding Fathers. So that’s the fun we have with hip-hop, in using the artists and the way they deliver those lines to inform our characters.

DL: Your songs also grow out of the tradition of musical theater. Would you talk a little bit about your love of past musicals that fed into your writing of Hamilton?

LMM: Hamilton is influenced by Andrew Lloyd Webber in its structure, in that, we have our main character’s nemesis as our chief narrator, Aaron Burr. This harkens back to Judas in the opening of Jesus Christ Superstar and Che popping up throughout Evita. Burr owes a huge debt to those forefathers in the musical theater canon. This is a very different show from In the Heights, when we looked at Cabaret and Fiddler on the Roof, shows about community and communities changing, a great tradition of musicals where that is the larger structure. With this show, I studied Mama Rose from Gypsy, Sweeney Todd, and The Unsinkable Molly Brown, and those musicals that are really about one person and the whirlwind they create in the lives of everyone they touch. So our opening number, originally conceived as a monologue, owes a huge debt to the opening monologue of Sweeney Todd where all the characters come out and you don’t know who they are yet or the role they are going to play, but tonight we are going to tell you the story of Sweeney Todd. Another thing I enjoy about musical theater is that it will take any genre of music it needs to tell its story, whether you are talking about pure jazz for City of Angels or emo for Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson or the way Sondheim plays with eastern tonal and pentatonic scales for Pacific Overtures. That’s the fun of hip-hop and musical theater: we are not one art form or one genre of music. We are a genre that adopts and flips other genres to suit our purposes.

DL: Do you usually write your lyrics or music first? Or does it just come together?

LMM: It really depends on the song. I could point at every song in this though and point to a different method by which I got the song out. In the opening number, I was writing the lyrics in a void before I set the music to them. “My Shot” was the same, the lyrics came way before the music but then once the music came you take another pass at it and you begin writing the harmonies and you begin writing the underpinnings and that informs. So it kind of doubles back over itself. Eliza’s song to Hamilton called “That Would Be Enough,” everything came all at once. Some of these songs are like really tough crossword puzzles. “The Room Where It Happens,” which is Burr trying to get at what really happened in a political backroom, took me two weeks, and I puzzled it out by myself. I actually stayed at producer Jeffrey Seller’s house, he lent me the keys and I went there alone with my dog. And as my dog chased squirrels and geese in his backyard I puzzled out the giant Sudoku that is, “The Room Where It Happens.”

DL: Great Song. It reminds me of “Someone in a Tree” from Stephen Sondheim’s Pacific Overtures.

LMM: Absolutely! Which is Sondheim’s favorite song. It’s a beautiful song. And it speaks to a larger question, “How do you pack so much history into one show?”—which is you can get away with anything if it is also serving your story. The story of trading a debt plan and votes in Congress for the location of the capital of our country could be a pretty boring, dry, history lesson. But if you tell it through the prism of the one guy who wasn’t invited to the party and is dying to have power and is realizing the parade has passed him by, then suddenly it’s gripping because we are trying to get all that information, we are trying to get into that room. And that’s how we approached all the history; you can get away with any history nerdery you want but the political always has to be personal.

DL: What songs that you wrote are you most proud of in Hamilton?

LMM: I’m proud of this thing as a whole and the way it hangs together as a score. The debt it owes to Les Misérables is the use of themes and bringing those themes back in moments where you don’t expect them; they come back in a different and ironic way. I think about the counting that we used to set up “Ten Duel Commandments” that explain the rules of dueling. But then we used that same melody as poor nine-year-old Philip’s exercise as foreshadowing to his death in a duel. He is doing the same intervals and same numbers but is singing them in French at the piano with his mother. I’m just proud of the way it’s through-composed. That being said, its no secret that Aaron Burr has the most fun songs in the show. “Wait for It” and “The Room Where It Happens” are two of the best songs I have ever written. I just think that Leslie Odom Jr. delivers them beautifully, and I’m also particularly proud of “Satisfied” which is Angelica’s big song. I went about writing that like I was writing an eighth-grade personal literary essay. This is the thesis, and here are three proofs, and here is the conclusion. I wanted to speak to Angelica’s intelligence and emotional intelligence, she knows Hamilton better than himself the second that she meets him. I love that about her, and it was a joy to write that.

DL: What was your greatest challenge when you were directing the show?

TK: Making sure everything on stage was moving the story forward at all times. When you are working on something that existed in the past and there is a book or timeline you can reference, it is easy for it to become a series of events and not a story. So my job, along with Lin and my other collaborators, was that we were always telling the story of how this man rose and how this man fell, and we knew that this architecture had to be honored at every moment in the show. What I am most proud of with the show is the comprehensive and thorough unified shape. If I do it right, my work is often not seen but is felt.

DL: Is it different directing an historical piece versus a contemporary piece?

TK: In some ways yes, because there is a roadmap that exists, there is what actually happened and so you can use that as it serves you. We tried to be very authentic and honest to the accuracy of the events, and more importantly, to the essential qualities of the characters in Hamilton’s life, both as protagonists and antagonists for his trajectory. But when you work with something wholly original, like In the Heights, it can go anywhere and the fact that there is that much open road poses another set of problems. We knew that there were places we could not go in Hamilton just by nature of the things that actually happened. It gave us a framework that I found very comforting, and we departed very rarely from our version of this historical truth. I think that this actually gave us a lot of ability within that structure to be creative.

DL: Was it decided from the beginning to cast the roles with mostly non-white actors? Why do you think it works so well for the show?

LMM: Frankly, it happened very organically. It was always going to be like this, it wasn’t a decision to do it. That’s coming from a place of “Wouldn’t it be novel?” It was never novel for us. When I started reading this book, I was picturing hip-hop and R&B artists singing these songs. So they were always people of color. It’s the most natural fit for this genre of music. So part of it stems from the initial impulse of writing the show, and Tommy continued the impulse and double downed on it. He basically said, “This had got to look like our country looks now.” Our goal in every aspect of the production from costumes to choreography is to eliminate any distance between a contemporary audience and the story which took place 211 years ago. So to that end, casting the show the way our country looks today helps. Our choreography has some elements from then and some elements from now—everybody is basically period from the neck down and contemporary from the neck up. So there are contemporary hairstyles against these period outfits which just looks so cool. You can get lost in the world of the story and you don’t feel it’s a dry history lesson.

TK: If we made a show about the world then, that looked like the world now, we knew that it would give us access to the ownership of our story—that’s “our” meaning all of us. Hopefully this is something that transcends beyond only Americans because it’s about the formation of an idea—and how that seed can then grow into a country. Everybody is from somewhere. So one of the things we also wanted to do by making the decisions we did in casting is remind ourselves and the audience that this was a country founded and made by people who came from somewhere else. We wanted to try to knock some of the dust off the statues that existed and make them full-bodied and human.

DL: Would the two of you talk about your working relationship with each other?

LMM: When you hire Tommy as a director you get a two-for-one because he is also one of the best dramaturges around. He has such an incredible sense of story. A lot of the dramaturgical decisions that went into the structure of this show are from conversations with and suggestions from Tommy. It’s not just about making stage pictures or staging the show with him; he is with you every step of the process in terms of shaping the show and forming the show. He lets you know when you are treading water, if you can get somewhere faster. It’s actually kind of hard to overstate it. And when you compound that with the collaboration with Alex Lacamoire who is basically our musical dramaturge and reinforces the repeated themes through his orchestrations and arrangements and find surprising new ones. And choreographer Andy Blackenbuehler, who is making his own parallel, physical score. This is something you get on the fifth viewing but whenever Aaron Burr is onstage, everything is in boxes, everything is super straight and linear; anytime Hamilton is onstage, everything is in circles. It’s subliminal but it’s the way the bodies are setting up these characters and the way they are interacting with the world and it just adds to the tension. The fun of my job is that I write the songs and I bring them in, and it’s like this great show-and-tell where I have these world-class collaborators who make my work better at every stage.

TK: One of the most striking things about Lin is his openness once he trusts you. That’s the fundamental difference between working now and when we first started; neither of us has to prove anything to each other in terms of our intention, which is always to make the thing better—to make the song better, to make the moment better, to make it sharper, to make it deeper. Lin knows implicitly that all I’m trying to do is service the piece. He learned that very early on with In the Heights. Effectively, our shorthand has gotten shorter. It’s now almost subliminal and non-verbal. There are times when I can just look at him and he knows exactly what I’m going to say and vise-versa.

DL: How do you think this show relates to the political climate of today?

LMM: I think it’s pretty awesome that we are coming in on a presidential election year. The net results being, the Democratic debates happen and I get 50 tweets about “Talk less, smile more,” or phrases from my show. Someone makes a gaff and people start tweeting me, “Well, he’s never gonna be president now.” So that relevance was totally accidental but you have to remember that musicals are born when they are born and some take two years and some take seven years. So what’s fun about writing Hamilton is that the issues they dealt with at the birth of our democracy are the issues we are still dealing with now. It’s immigration, it’s how involved are we in the affairs of other countries, when are we a state, when are we one country, what are the rights of our government over our citizens? Those are all issues we are still wrestling with. It gives me hope to know that it’s not like America was this Eden and we fell from it—we’ve always been fighting and debating about these things. I’m glad we landed in election times, but I think these themes would have resonated no matter when we opened because they are themes we wrestle with as Americans.

DL: Critics have called this show a game changer in musical theater. What is your reaction to that?

LMM: I don’t know what game we are playing and why we have to change it. This is sort of everything I know about writing musicals in one show. You hope that every time you write a show it’s that, but that isn’t always the case. It’s amazing when you put out work, and you see it influence other people. George Takei credits In the Heights with his impulse to write Allegiance. He heard “Inutil,” a song about a Puerto Rican guy not being able to pay for his daughter’s college, and he started thinking about his father and what his parents sacrificed for him and their experience in the internment camps during World War II. I remember actress Priscilla Lopez telling me very early in this process, “You have no idea when you make a show, the ripples it’s going to have.” I’m starting to feel the ripples of In the Heights right now but I don’t know what the ripples from Hamilton are going to be yet. You can see the ripples of Sweeney Todd and Jesus Christ Superstar and Les Misérables. And that’s the fun of this; we are links in a chain. Hamilton is in many ways an old-fashioned musical. I am using contemporary music to tell this archetypal American story. I am drawing on the traditions that I grew up loving in musical theater, and I think that’s also resonating with people. I’m not trying to tear down musical theater for them.

TK: I see this show as a love-letter to all the shows that came before us. We weren’t trying to change anything, we were basically trying to take all the things that inspired us and synthesize them and find our own voice. It’s hard for me to identify what that would mean. I’m also way too inside of it to be able to really say that and far be it from me to think that we intended something because we didn’t intend to do anything but to try to tell the story. The lineage of our show is Gypsy, Sweeney Todd, Evita, Jesus Christ Superstar, and a little bit of Les Miserables sprinkled in. Those are the grandparents of our show, and all of those shows are coursing through as well as all the plays we’ve done, all the Shakespeare we’ve seen—the fact that our show has an opening number that frames the whole thing, much like a prologue in Shakespeare where it allows your ear to transition into the language—because the story doesn’t really start until the second song, the “Aaron Burr, Sir” to “My Shot.” We were inspired by, took from, and were challenged by all the things that came before, and that’s where our focus was—trying to honor that.

DL: Your songs are difficult to perform but you have this great cast. Can you talk a little bit about working with these actors and seeing them perform their songs?

LMM: I think we have the best cast on Broadway. What they do is pretty miraculous. They don’t teach you how to rap at musical theater school. I went to Wesleyan which teaches you avant-garde theater and mechanics. I was one of the only people making musicals at Wesleyan when I was there. But what is exciting is that there is a generation of performers who are like me. They didn’t necessarily get to rap in the school play, but they grew up to hip-hop, they grew up to this music.

DL: I was so impressed with everyone in the cast, especially the women. The songs written for women were fantastic.

LMM: I first saw Phillipa Soo in Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812. Tommy and I both saw that show separately but both agreed that woman was a star. When we were looking for an Eliza at one of our workshops, her name came up, and as soon as she was in she never left. And similarly with Renée Elise Goldsberry, who was one of the last to join us. We had had lots of really talented Angelicas and then Renée came in and actually spoke at the speed Angelica talks. Like when she sings “Satisfied,” it doesn’t seem like an actress working hard to get a bunch of words out. With Renée, it just tumbles out. She’s such a good actress, she keeps you with her train of thought even though that train is working at bullet speed.

TK: It’s been an extraordinary experience working with this group of incredibly gifted and generous artists who are as committed to the telling of this story and the creation of this show as anyone could ever hope for. I’ve worked harder than I’ve ever worked in my life and I also had more fun than I ever had in my life. It’s a group of people who are absolutely at the top of their game, but are even better human beings than they are performers. That’s the thing I’m most proud of with this company; it is how they wave the flag of this show and how they are each ambassadors of this show in their own way and then collectively come together to tell the story.

DL: You do have one or two actors in your show that have done rap before right?

LMM: Christopher Jackson is our veteran from In the Heights. He comes with this amazing moral authority. He influenced the character Benny and the writing of it because he was just more compelling than the character I’d written. I started writing to him instead of this Latino character from the initial version, so I made him an African American for Chris Jackson so that he could bring more of himself into the role. And Daveed Diggs works with Freestyle Love Supreme so I knew he was an incredible rapper—I didn’t know if he could sing or act. But we just invited him to do one of the workshops and then it was a wrap—well, that was that. We just kept giving him hoops to jump through and they were like nothing to him.

DL: Has your family background inspired some of the show?

LMM: I don’t think it is a coincidence that my father came to New York at the same age as Alexander Hamilton. He came to get his education just like Hamilton and he had the additional barrier of not speaking a word of English—he learned English here in the city. So I think my father was very much on my mind when I was writing. I also grew up in a political household—my father has been involved in Democratic politics in New York for as long as I can remember. So if there was a room where it happened I was usually in the back coloring or playing a video game. It’s interesting— Governor Cuomo was at the show earlier this week and he said, “I can tell you absorbed politics at the kitchen table.” It’s just infused in how I write. My mom was a psychologist; my dad works in politics—that’s a pretty good recipe for how to create a Hamilton.

DL: I’ve seen the show twice now, and the reaction has been rapturous. What do you think of the visceral reaction from the audience? What do you think is going on?

LMM: I think they are surprised that they are so moved. Everyone comes and hears “hip-hop musical about Alexander Hamilton,” they think, “Oh, this is going to be clever, maybe this is the ‘snob hit’.” Like, this is going to very arch and it’s going to be funny, and the distance between the style and the subject matter is going to make for a humorous show. I don’t think they are ready for the sucker punch of Hamilton’s tragic life. It’s really structured as a tragedy—this man’s strength, his gift with words, is also his downfall. And the fact that his wife Eliza Hamilton is the one to tell his story is also part of that sucker punch. You know, you hope that when you die that the people who love you are going to remember you and will carry on your memory. To see that story traverse the distance between when it happened and today, it adds up to this very looming moment. We all want to be remembered. Whether it’s on a grand scale or just by the people who loved us. I think that’s a very primal chord we are touching on.

DL: Lin, you recently received the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship, what does that mean to you?

LMM: It’s a giant vote of confidence from the universe. It’s very crazy because they call it the “genius” grant, so everyone calls you a genius for the next couple of weeks. And then it drives your wife crazy a little bit. What’s amazing about that fellowship is that there are no strings are attached—I don’t have to go to a gala, I don’t have to vote on work. It’s just like, “Here’s some money, just keep doing what you do.” I don’t see it as pressure—I see it as, “Double down on the things you love, because the things you love are what got you this grant.”

DL: What are you working on next?

LMM: I’m co-writing the score for a Disney animated musical, Moana, that comes out next November. I’ve been working on that for the past year and a half. I got the gig the week that we found out we were having our first child. The musical takes place in the Pacific Islands. I’m working with another composer, Opetaia Foa’i, who is from there, and Mark Mancina, who did the score for The Lion King. So the three of us are creating this musical landscape that feels authentic to that part of the world. It’s a lot of fun.

DL: Thomas, your next project is directing Grease for live television on Fox on January 31. What challenges are you are facing for that?

TK: The challenge you are facing is that basically you are putting your preview, your first run-through and last run-through, in front of millions of people. The show has a lot of moving parts, and as always, my job is to make sure we are all telling the same story, in the same way and on the same page. It doesn’t matter if it is a live broadcast for a million people, or doing a play downtown for 65. My feeling is that Grease is a big party and everybody is invited—that was the spirit of the show in the ’70s and that is what the movie is as well.

DL: In the spring, you’re also directing plays at the Public and the Signature theaters in New York City, can you talk about that?

TK: I was just in auditions with Quiara Alegría Hudes [the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright who wrote the book for In the Heights and currently teaches at Wesleyan], and we are doing her new play Daphne’s Dive at the Signature Theater. Quiara and I have been working on it for a few years, and it’s been wonderful back sitting in a room with her making something. The play takes place in a bar in Philadelphia over the course of 20 years so it spends time with the folks that come and go in the bar. I think it is some of her finest writing.

The play at the Public Theater is called Dry Powder by a new writer, Sarah Burgess, and it’s her first professional production; John Krasinski stars in it, whom I think is going to be fantastic. It’s a four-character play—very funny and sharp—set in the world of private equity. It’s basically a morality play. Our hope is, just like when I did a play about football, that we will tell the story with integrity. I want people who work in hedge funds and Wall Street to feel like we are doing something that has real authenticity. Making work that is honest and true is really at the core of everything that I try to do.