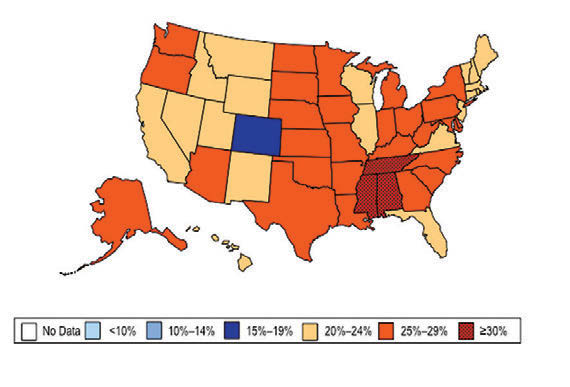

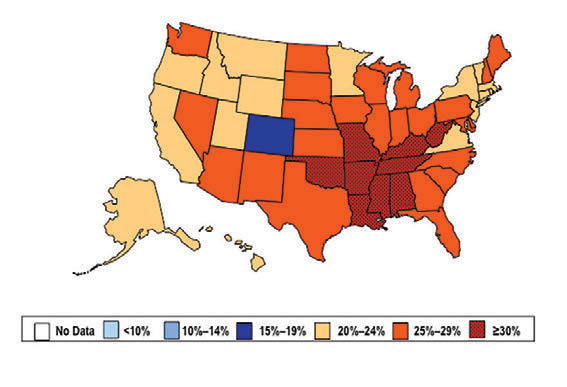

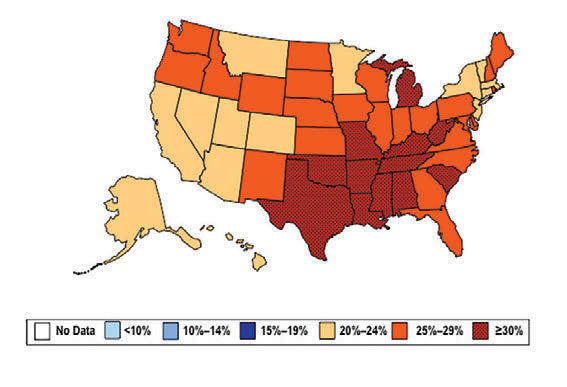

Mapping the OBESITY EPIDEMIC

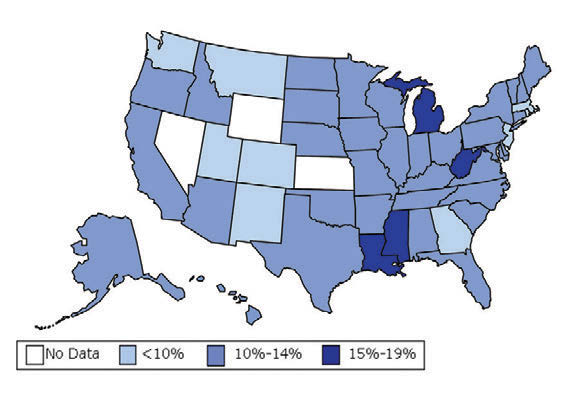

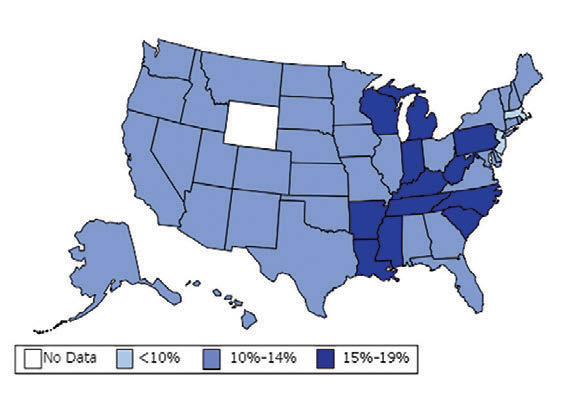

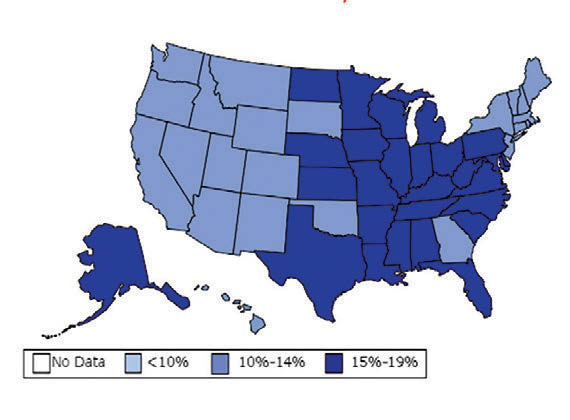

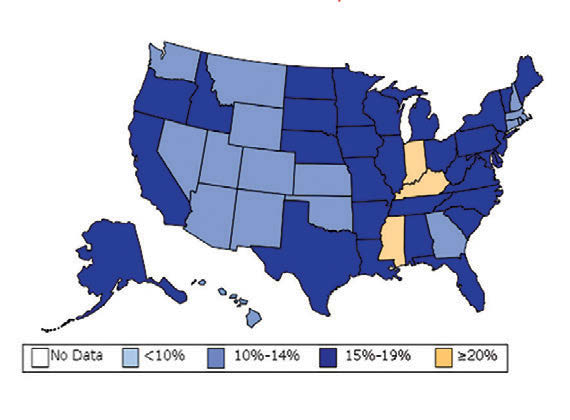

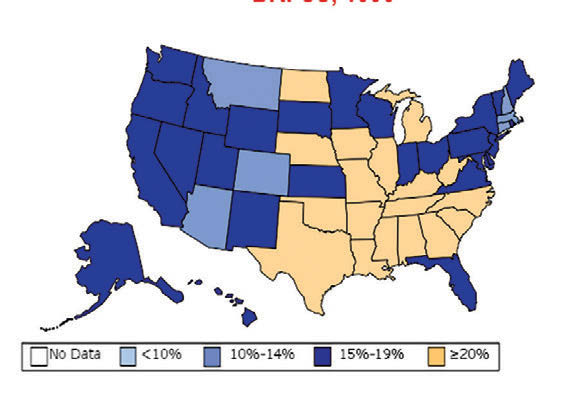

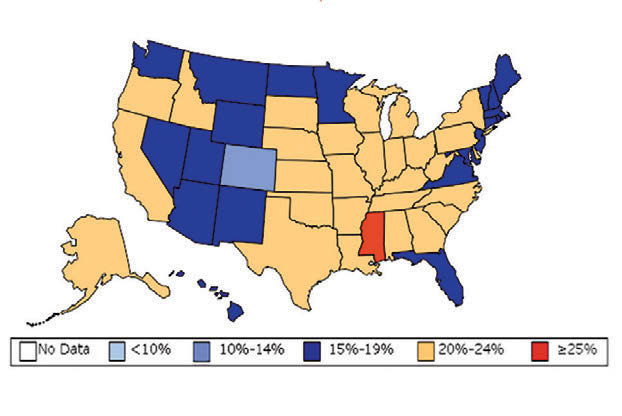

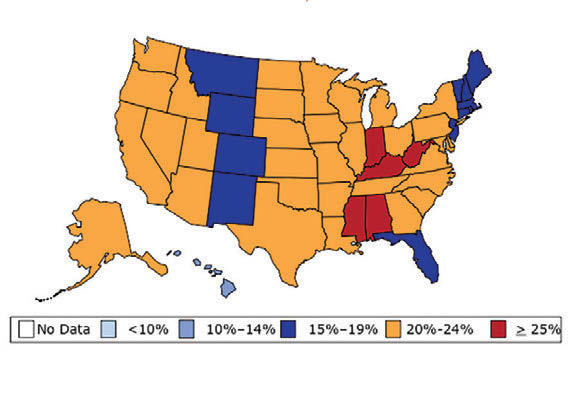

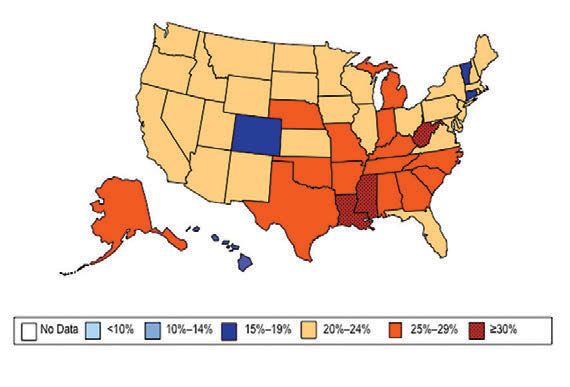

William H. Dietz ’66, MD, PhD, director of the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness at George Washington University, is one of the leading experts on obesity. In 1997, as the director of the Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Dietz’s maps (see below) changed our understanding of obesity from a “mainly cosmetic” condition to a major public health concern.

Bill Dietz arrives at his office at the Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness at George Washington University wearing sneakers and a backpack, straight from the Metro. Three mornings a week, he’s already put in time swimming laps—an activity he’s kept up since his days on Wesleyan’s team. Asked about use of an app to record physical activity, he shakes his head: “I know when I’m active.”

Dietz is one of the world’s leading experts on obesity—a reputation he cemented while at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). He recalls one of the first conversations he had as director of the Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity in 1997. It changed the way the country understood obesity.

“You know, we have height-weight data by state,” a colleague mentioned in passing. The data were self-reported statistics from an annual telephone survey, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. “It struck me then,” Dietz recalls, “that if we could display those data, we would have a pretty compelling argument about the spread of obesity.”

When he first presented this map collection internally: “It blew everyone out of the water,” he says.

And it continued to compel attention. In 1999, The Journal of the American Medical Association published the maps in its first issue devoted to obesity. CDC Director Jeff Koplan joined Dietz in co-authoring an editorial declaring obesity a national epidemic, calling for a public health response. Two years later, Surgeon General David Satcher issued a federal response: The Surgeon General’s Call To Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity, which outlined recommended policy initiatives.

“Those maps are the most effective visual I’ve ever done,” Dietz muses. “And when we map diabetes on a state-by-state basis, those maps parallel the obesity trends.”

ASKING THE QUESTIONS

Dietz began his sojourn in the world of obesity at MIT for his doctoral work in what was then the Department of Nutrition and Food Science. In the rich academic environment that is Boston, he collaborated with Steven Gortmaker P’17 of Harvard’s School of Public Health on epidemiological studies—beginning with the effect of television on obesity in children. (Yes, it’s a factor; Dietz calls out advertising companies that use television to market food to children.) After completing his doctorate at MIT, he received an appointment as the director of clinical nutrition in the Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition at the Floating Hospital of the New England Medical Center, part of Tufts University, and as associate director of the Clinical Research Center at MIT.

Throughout his career, he’s been driven by an interest in questions that nobody can answer, “because those questions define a frontier of knowledge,” he says.

“When I began my research in the 1970s, people saw obesity mainly as a cosmetic problem. Only three people in the country were working on childhood obesity. There were lots of questions without answers.”

As he continued his work at MIT and the Floating Hospital, not only did he revel in the climate to test out common physiological theories, such as “people with obesity have slower metabolisms” (they don’t); “you’ll burn more fat molecules on a diet free of carbohydrates” (you won’t); and “people with obesity have less lean mass than those without” (they don’t), but as director of an obesity clinic at the New England Medical Center he was able to involve himself in the psychology of those with obesity.

“One evening I was talking to an adolescent girl, and she blurted out, ‘I eat to keep people away from me.’ She’d been sexually abused as a child, so her obesity served quite literally as distance between herself and others.” Dietz added a family therapist to his team.

“That’s one of the things about obesity,” he says. “It’s intensely personal. Everyone has a story.”

“PEOPLE WITH OBESITY”

Eager to elevate the concern about rising obesity levels to the national stage, in 1997 Dietz moved to the CDC (“an activist agency,” he notes). There, he published a paper, in collaboration with an internist at Kaiser Permanente in Southern California, showing that severe obesity in women was associated with adverse childhood experiences.

“Research on this is exploding,” Dietz notes.

“Numerous adverse childhood experiences—poverty; verbal, physical, and sexual abuse; homelessness; hunger; parental incarceration, alcoholism or drug addiction; racism; and divorce—are factors that predict severe obesity in adults.

“It’s tempting to say, ‘Well, these are problems for kids in urban poverty.’ But in fact, this is an American problem—and one that we’re going to see more of every year. The opioid epidemic is turning out a whole new generation suffering adverse childhood experiences because their parents are addicted.”

Noting that not every child in adversity will have obesity, he asks, “How do you build resilience in a child living in a community characterized by opioid addiction, poverty, or violence? How do you build resilience within a community? These point to the deep-seated social determinants of obesity that we need to explore and mitigate.”

What is the core information, he asks, that everybody who sees a patient with obesity should know? One element is understanding the role of stigma and bias, and the need for people-first language—“people with obesity,” rather than “obese people.’”

“We don’t talk about ‘diabetes people’ or ‘cancer people.’ Yet we talk about ‘obese people.’ One of my mini-crusades is to get people-first language integrated throughout the literature. It has to start with us.”

MAKING THE RIGHT CHOICE EASIER

Although obesity is an intensely individual problem, it is also an illness of epidemic proportions taking a toll on collective resources.

“One of the other critical studies we did was a collaboration with Eric Finkelstein at RTI, showing the costs of obesity. It was really the first study on the economics of the condition. Obesity is a huge contributor to health care costs—and about half those costs are borne by Medicare and Medicaid, about 10 percent of the national health care budgets. It was pivotal in calling attention to the epidemic.”

With these concerns delineated, the call came for policy initiatives. Dietz’s team set about developing responses within community frameworks—child-care centers, schools, and workplaces—that would provide healthier daily options to these groups. This, ultimately, would result in lower national health-care costs.

To begin, the CDC team set up a wellness project at their own worksite, including more healthful cafeteria options, with marked success. “Health and Human Services adopted the standards, which are now governmentwide,” Dietz notes. “It is very likely that we’ll begin to find significant improvements in the health of the federal workforce in the future.”

The team also experimented with attracting would-be elevator passengers toward the stairs. At first they gave the cement stairwells new carpeting, fresh paint, and attractive posters, from tropical fish to mountain vistas. These changes had no effect on stair use. Health-based prompts to use the stairs increased usage, but this bump lasted only three months.

Dietz’s theory: “The prompts just became part of the wallpaper.” So next they tried music, an ever-changing element. Again, the stair usage increased —but this time it lasted.

“Over time,” says Dietz, “we developed a portfolio of policy recommendations and strategies that provide the community and individuals with a framework of healthy alternatives throughout daily life.”

TRANSFORMING THE DISCUSSION

One of his deepest concerns about the nation’s diet hearkens back to one of his earliest— and most noteworthy—papers. In 1985, Dietz and Gortmaker published the first study of the effect of television on childhood obesity, suggesting that the relationship was causal.

While “television time” is likely to be enfolded in “screen time” now, Dietz maintains the two are different: TV ads market food to children. At the CDC, Dietz and his colleagues developed standards for these “kids foods,” calling for lowered sodium, sugar, and saturated- fat content, and presented their report to Congress. Although the hearings proved contentious, Dietz notes that the children’s food and beverage advertising initiative did adjust their standards—although not, he says, to the degree his team had recommended.

Later, as Michelle Obama gathered information for her Let’s Move campaign, Dietz and his CDC colleagues provided important contributions to the development of her program.

“When you go back to look at the report her team produced, it reflects many of the strategies that the CDC was developing. Our work underpinned many of programs that the Obama administration initiated and the issues they have tackled around childhood obesity,” he says, including breastfeeding; food marketing; changing standards; the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act for schools; and child and adult-care food program regulations.

“Having Michelle Obama out front on children’s health made an enormous difference,” he notes. “When the First Lady started talking about the impact childhood obesity had on her parenting, that began to transform the discussion. She gave it more visibility than any of the agencies could have achieved on their own. She has been extraordinary.”

“LET’S TALK ABOUT SUGAR”

If there’s one particular food item that Dietz would like to eliminate, it’s what he calls “sugar drinks”—specifically, sodas.

“Let’s talk about sugar,” he says. “Sugar drinks are the main source of sugar in our diet. Added sugar in our diet has declined, mostly because soda consumption has declined. But added sugar in our diet is ubiquitous; it’s a browning agent to make baked goods look attractive. A lot of this is fructose.

“I think we can now say that sugar drinks are a cause of obesity—there’s enough evidence,” he says. “Roughly 16 percent of adolescents, and about 20 percent of young adults, are drinking more than 500 calories per day from sugar drinks. And sugar drink consumption is greater in African American and Hispanic populations, greater in low-income populations, greater in less educated populations.”

One way to cut this consumption is by using “traffic light” colors as labels. A number of hospitals in Boston, he says, have begun using red labels for the sugar drinks, yellow for the more healthful choices, and green for the most healthful choices. Additionally, “choice architecture” makes reaching for the sugar drink a little more complicated. If red drinks are located in a separate fridge not immediately visible, or on a shelf above or below eye level, then the yellow or green drinks become grab-and-go’s. These are nudges—strategies that make the default option the healthier choice, not unlike music enticing people to the stairways. As with tobacco, the most effective strategy will be to tax sugar drinks, he says.

STAY ACTIVE WITH A DOG

Now at the Redstone Center, Dietz enjoys working at the community level—still on obesity, physical activity, and health. He cochairs the Diabesity (“yes, that’s obesity and diabetes—they go together”) Committee at the D.C. Department of Health. He’s exploring preventive health care measures, with some trials indicating that behavioral interventions are actually more effective than medication in warding off type 2 diabetes. He’s studying concerns that are both specific to the District of Columbia and common to many cities across America: “One of our major challenges is food equity,” he says. “We have very substantial ethnic disparities when you track almost anything: food access, disease rates, and poverty.”

He is also championing a new initiative, urging all D.C. hospitals to eliminate sugar drinks from their dining facilities.

“We think if we start with the hospitals— which, by virtue of their mission, should be concerned about the health of patients, visitors, and employees—then we may begin to turn the tide and decrease the prevalence of obesity and diabetes.”

Imagining a sugar-drink-free hospital, he offers this comparison: “When I was in medical school, we’d walk into grand rounds and light up a cigarette. Really, it was a smokefilled room. Then I went to Panama with the Public Health Service for three years. When I came back, the hospitals were smoke free, gift shops no longer sold cigarettes, and vending machines were gone. I think we can transform social norms about sugar drinks in the same way.”

One final piece of advice from Dietz: if you want to stay physically active, he suggests going to an animal shelter and getting a dog. “Fifty percent of the U.S. population have dogs,” says Dietz. “And 50 percent of people with dogs meet their daily physical activity requirements— probably because they’re walking their dogs.”