PORTRAIT OF AN ARTIST: AN INTERVIEW WITH JULIA L. KAY ’83

When computer-analyst-by-day-artist-by-night Julia L. Kay ’83 invited fellow artists to draw each other via an online portrait drawing group, she had no idea how many, if any, would respond. Today, almost 1,000 artists from 55 countries have contributed 50,000 creations to Kay’s international online collaborative art project, Julia Kay’s Portrait Party (JKPP).

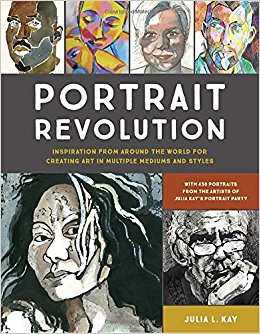

Julia L. Kay ’83 is a painter, printmaker, photographer, muralist and digital artist. Her book, Portrait Revolution: Inspiration from around the World for Creating Art in Multiple Mediums and Styles (Pimpernel Press, UK and Watson-Guptill, USA), draws from the 50,000+ portraits made by almost 1,000 artist-members from 55 countries in her online Flickr group, Julia Kay’s Portrait Party (JKPP). Visit or join the group at studiojuliakay.com/jkpp. Read more about Kay—and see more of her work—in Wesleyan magazine.

Where did you grow up, and how did you end up at Wesleyan?

I grew up in New York City. We lived in Queens until mid-high school, then moved to midtown Manhattan—a very exciting location for a young artist to be! I’m not sure how Wesleyan first came to my attention, but I know I was interested enough for my parents to arrange with a family friend to drive us up to campus to visit, as we didn’t have a car. Although I applied to several schools, Wesleyan was the only one to warrant a visit. My main memory from the trip is of the beautiful Center for the Arts—the large studios with glass walls and great light.

Did you always want to be an artist—or did an “ah-ha” moment lead you in that direction?

I wanted to be an artist from a very early age, though I also considered being a veterinarian or a clown. I have very clear memories of both finger painting and being in museums with my mother when I was very young, and I’ve always liked to look closely at the world and to make things.

When did your art start focusing on portraiture?

For most of the ’90s and early 2000s I lived in large live-work warehouses and made mural-sized paintings [at left]. My living spaces were hard to heat, hard to cool, and hard to keep clean, but I was clearly living the life of an artist. The paintings were hard to sell, hard to move, and hard to store, but they made a big statement.

In the mid-2000s, I found myself happily living with my partner in a real house. The master bedroom was my studio and I had east- and north-facing windows with great light. All should have been well, but I was having trouble finding my way in the new studio. The house constrained the size of my paintings, other commitments reduced the amount of time I could devote to painting, and I no longer had the intense western light that had poured into my previous studio every late afternoon and cast fabulous shadows of my tropical plants across the studio floor. I needed a new subject.

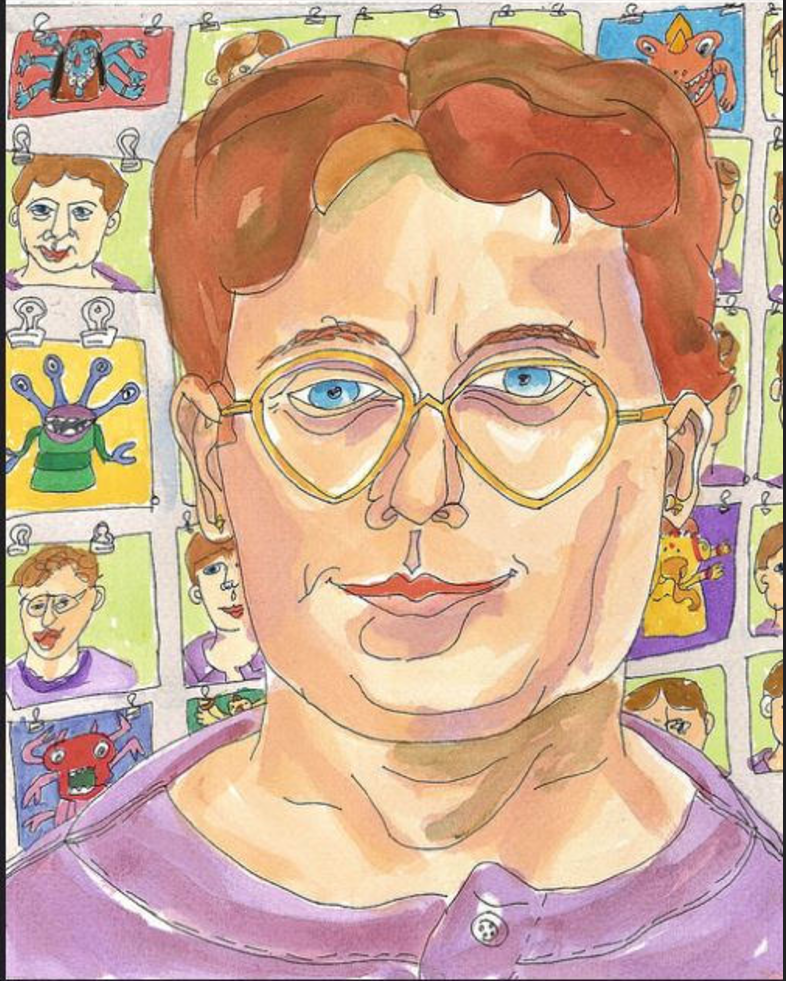

Over the course of a couple years, I wandered through different subjects and series but nothing really took off for me. I was feeling very frustrated on March 15, 2007, when I stood at my studio table and scribbled a magic marker drawing of my face. It only took me a few minutes to make that drawing, and I thought to myself, “Well, okay. You don’t have a lot of time every day. What if you just do this—just make an image of yourself every day?” And the Daily Portrait Project was born.

For three years, I drew myself every day. In sickness and in health, camping in the mountains and camped in my partner’s hospital room, at home in the middle of the day and in hotel bathrooms in the middle of the night, I drew myself.

After the first few months, friends asked how long I planned to continue, and I replied as long as it’s interesting. Months became years. People learned of the project, checked in on it for a while, got caught up in other things, and were surprised to find months or years later that, yes, I was still drawing myself every day. Halfway through the third year, I started thinking it was time. And on March 15th, the third anniversary, I ended as I began, with a simple green line drawing of tousled hair and mock turtleneck, large glasses and double chin.

How did the arrival of the iPhone impact your art-making process—and how did it lead you to get involved with the online artist community on Flickr?

It’s hard to remember now, but when the iPhone and iPod Touch first came out, there was no app store. There were no apps other than those that came on the phone, though you could get some added functionality from web pages that were customized for the phone interface. When the app store opened, the first art app I found was called No. 2—like the pencil—and I downloaded it and made a self-portrait right away. The app developer was asking everyone using his app to upload their artwork to the group he had started on Flickr, so I did that, and then started looking around for other groups to join. I found one for “finger painting” on touch-sensitive screens, and that group was extremely welcoming and enthusiastic—in fact I’ve now met many of the core members of that group in person. Everyone was sharing tips and techniques and letting each other know about the latest apps.

But while I was excited about drawing on my iPod Touch, I wasn’t giving up on all the traditional media, so I looked around for those groups, too. More importantly, since most of my work at that point was self-portraits, I joined some self-portrait groups and started following and chatting with self-portrait artists all around the world. The “founding” members of JKPP came mainly from those two groups: mobile digital artists making work on any subject and self-portrait artists making work in any media.

What was your inspiration for starting Julia Kay’s Portrait Party (JKPP) on Flickr?

JKPP began in 2010 as a way to celebrate the successful completion of my self-portrait project. During that time, I had experimented with multiple media and conceptions of “self-portrait.” I drew while looking in the mirror, from photographs, from memory and from imagination. I painted in my studio and drew with my finger on my iPod Touch. In all this experimentation, the thing that emerged as the most important to me was my commitment to a daily art-making practice. I had never had that in my life before, and it was terrific. After three years, I was ready to stop putting myself in every picture, but I wasn’t ready to stop drawing every day.

As a transition between staring at my own face for three years and opening up to other genres entirely, I thought it would be fun to throw a portrait party and look at some other faces. I’d first heard of portrait parties from Rama Hughes’s blog, where he described a portrait party as a get-together where artists draw each other. Originally, I thought I would have a traditional live portrait party.

Unfortunately, as the three years of my self-portraits were winding up, I found myself in no position to throw a live party. I’d begun posting my work and following other artists on Flickr, so I decided to try starting a group there. I sent invites to some of the other self-portrait and figurative artists I’d been interacting with, crossed my fingers, and hoped a couple of people would post photos by the time I was ready to start, a week later. The rest is history.

Can you explain how JKPP works?

Everyone starts a discussion topic within the group, adds some self-portrait photos, and in doing so gives group members permission to make derivative artworks based on those photos. When members make portraits from the photos or from life, Skype, etc., they add them to the group image pool and also add them to the subject’s discussion. That way there is one place to go to see all of the photos and all of the portraits of each person.

It’s entirely up to each member how many portraits they make, which subjects they portray, how frequently they participate, etc. Some members go through and make a portrait of each member, others return multiple times to a favorite subject. It’s common for someone to be very, very active for a while, then follow some other artistic interests but stay in touch with the group and “drop in” to make a portrait every now and then.

Were you surprised by the group’s immediate popularity?

Yes, I was very surprised! I invited people a week before my three years of self-portraits were over, and I hoped at least one person would be willing to post a photo of themselves so I’d have a new subject to draw. I never imagined that in that first week, 60 artists would join and draw more than 200 portraits of each other. It turned out self-portrait artists all over the world were hungry for another subject to draw!

Why do you think JKPP is so popular?

I think there are a lot of factors, but one of the things I didn’t think about at the beginning is how personal portraiture is, for both the subject and the artist. When someone draws you, it really is different than if they draw your pet or your garden. Even if you don’t like the particular style or the particular portrait, you’re inherently interested in it because it’s you. And on the other side, to make a good portrait you spend time staring at the photos of the subject and trying to understand who they are based on their expressions, the context (are they in the mountains or in the office?), who is in the photo with them, and so on. Do they wear funny hats or are they quite serious? Even if they’re smiling, what emotions do you see in their eyes? This process is really quite intimate. Even though you’re not in a room together, you’re having a dialogue with the person through their photos and your portraits of them, because they also learn about you through your art. I think this is one reason why the community aspect was immediately quite strong in this group.

Tell us about your new book, Portrait Revolution. Who came up with the idea for the project?

Tell us about your new book, Portrait Revolution. Who came up with the idea for the project?

The group had had conversations about doing a book, but it hadn’t gotten very far. One of the members of JKPP, Anna Black, is also an editor at Pimpernel Press, a small publisher in the UK. She conceived the brilliant idea of a book about portraiture featuring JKPP artists, rather than a book about JKPP. I agreed with the idea, and she pitched it to her employer. They liked the idea but to make it work they needed a larger partner, so they pitched it to Watson-Guptill, an imprint of Penguin Random House. That whole process took a year or more. Once everyone was on board, it took close to another two years to actually make the book. I have to say, it is very satisfying to now be able to hold it in my hands, after this long process from concept to completion!

With 50,000+ portraits and 1,000 member-artists to choose from, what were your criteria for selecting artists and art to include in the book?

Curating the book was like doing an incredibly complex jigsaw puzzle. It wasn’t a matter of just picking my favorite portraits. Each portrait had to fit the topic and also work with all of the other portraits chosen for the topic. At the same time, I wanted to show as much diversity as possible: not just the diversity of media, styles and themes that are showcased in the book’s sections but also the diversity of artists and subjects. This included wanting to show artists and subjects who were younger and older, were just starting out or were already exhibiting artists, came from different countries of origin, had different cultural backgrounds, ethnicities, etc. I also wanted to show a range of conceptions of portraiture, from realistic renderings of head and shoulders with strong resemblance to portrayals of the person in activity, at a distance, or abstracted in some way. All of these factors are at play at JKPP, and I wanted the full scope to be present in the book—both the incredible diversity and how it all comes together as a solid body of portraiture.

I hope the book inspires people to express their own creativity in a multitude of ways, and to be open to new possibilities when viewing and thinking about art in general, and portraiture specifically. I hope it might open some doors for any of the included artists who are pursuing careers in the arts—that’s a very tough road. And this is more than I can really hope for, but we are living in interesting times, where nations and cultures seem to be turning inward. I would love if the story of our coming together across borders and religions and socio-demographics inspires people to resist that trend, to be open to each other, to respect and embrace the humanity we all share.

Do you favor digital or traditional art making—or a mix of the two?

I’m very interested in the different kinds of marks we can make, from drawing with my finger on fogged glass and wet sand to traditional drawing and painting media to digital media. I love the tactile and unpredictable qualities of traditional media, and how when you work large, you draw with your whole body in movement. With digital media I love the convenience—having a full-color art studio at my fingertips in museums, making quick drawings while waiting in line or on the bus, cleanly erasing or changing colors, changing proportions, trying out compositions, applying textures, filling a whole area with color quickly, etc. I’m very active in the mobile digital community, and I’ll be presenting at the Mobile Digital Art Conference in Palo Alto this summer. But at the same time I’m working on the Templeton Commission, a large oil painting in my Sun Dances series.

What’s your current favorite medium or style?

I’m very interested in the creative process and in learning new things—whether learning something new in a medium I already know or experimenting with a medium I just learned about. Last year I learned about Gelli plate printing—a type of monotype—and gouache resist, and had fun exploring both. I also like to challenge myself to draw in different ways, like with my eyes closed, the pen between my toes, with my nose on my iPad, etc. These are processes of discovery, and discovering new things is what keeps it interesting for me.

Are there any lessons you’ve learned or recommendations you’d like to share about the art-making process?

The best thing I ever did for myself as an artist was make the commitment to draw every day. I just passed 10 years of daily drawing, and although I probably accidentally miss a few days a year, overall the practice has kept me creating no matter what else is going on—including tight deadlines for the book! The other thing I recommend is all kinds of experimentation: Draw larger or smaller, with your other hand, with your feet. Throw water on the paper, hold the pen in your mouth, close your eyes. Try media that are new to you and see what they feel like. And don’t ever be afraid to make a drawing. The worst-case scenario is that you don’t like it and you throw it out without showing anyone. The best case scenario is you make something fun to look at. Either way, go on and make the next drawing and the next drawing and the next one . . .