RUSSIA TROUBLES CONFOUND U.S. FOREIGN POLICY

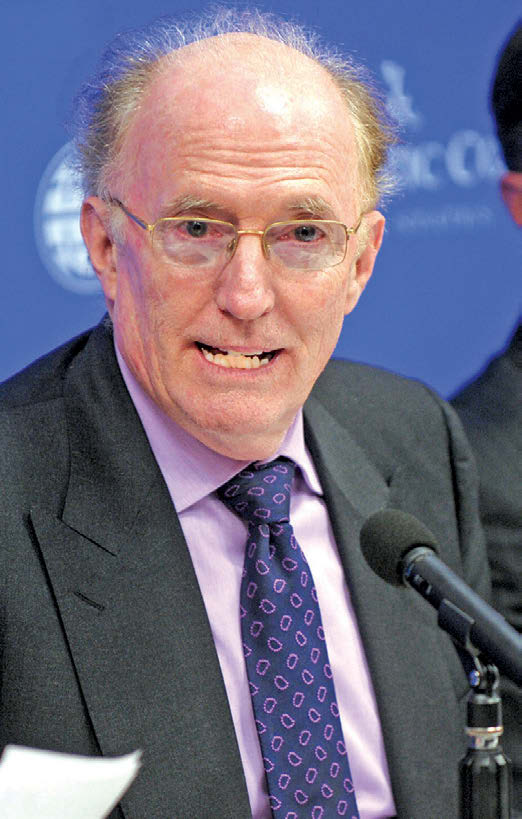

BY ROBERT HUNTER ’62

Robert Hunter ’62 is a former U.S. Ambassador to NATO who is recognized as a principal architect of NATO’s post-Cold War strategy. He has served as senior advisor at the RAND Corporation, a member of the National Security Council, and director of the Center for Transatlantic Security Studies at the National Defense University. He was foreign policy advisor to Senator Edward Kennedy and is a member of the American Academy of Diplomacy. A longer version of this article first appeared in Lobelog, a foreign policy blog (lobelog.com).

Debate in the United States during the first several months of the Donald J. Trump presidency has focused intensively on the role that Russia played in the 2016 U.S. elections, and on contacts between Trump supporters and Russian officials. These are not trivial matters. But they have implications far beyond the “real facts” of Russian actions; the impact they could have had on the outcome of the U.S. presidential election (almost surely marginal); and ties, if any, between Trump and Company and the Kremlin. The imbroglio is having a major impact on U.S. foreign policy and will very likely limit, because of U.S. domestic politics, American flexibility in dealing with Moscow—indeed, potentially reducing our capacity to pursue policies in our inherent national interests.

To understand how we got into this position, it is necessary to take a step back and examine the broader picture.

Almost never discussed in the United States is that Moscow did not out of the blue adopt policies at odds with and in many instances hostile to the West. Perhaps this was bound to happen; perhaps Moscow’s assertiveness, lack of respect for other countries’ security requirements, meddling in foreign politics, and unwillingness to abandon the classic notion of spheres of influence are part of Russian DNA. But seeing whether Russia could be induced to play a constructive role in mutually beneficial security and other arrangements, beginning in Europe, was not adequately tested. For too many people in the three U.S. administrations preceding Trump’s, Russia, once put down (as the Soviet Union) was to be kept down, however untenable that proposition always was and at variance with the West’s core security and other needs.

It didn’t begin that way. In 1989, U.S. President George H.W. Bush proposed an unprecedented grand strategy for a “Europe whole and free” and at peace. He understood that was by Russia must not be treated as Germany the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which, by assigning full blame for starting the World War to Berlin, sowed the seeds for German revanchism and World War II. Bush’s vision was translated into a set of interlocking steps. Central Europe was taken off the geopolitical chess board and Russia was offered a chance to play a major and respected role in the future of European security.

But even before Putin came to power, Washington lost interest in Bush’s vision. After NATO added three Central European countries to the alliance in 1998—in part to “surround” Germany with NATO, to reassure everyone that the German past was well and truly buried—the United States pressed for more NATO expansion, up to the Russian frontier. The George W. Bush administration unilaterally abrogated the 1972 U.S.- Soviet Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, one of the few remaining symbols of Russia’s great power past and likely future. Then, most consequentially, the 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest declared that “Ukraine and Georgia will become members of NATO,” thus violating a tacit bargain reached when NATO first took in new members from Central Europe. At that time and as a necessary complement to NATO’s expansion, it negotiated with Russia a Founding Act Security would on Mutual Relations, Cooperation, and Security. And to underscore that Ukraine would not become a pawn of great-power politics, NATO also concluded a Charter on a Distinctive Partnership with Kiev. It was understood that Ukraine would not be considered for NATO membership, at least without first seeing whether European security arrangements, supplementing NATO, could be developed in which Russia (and Ukraine) would be full partners.

With its 2008 Bucharest declaration on Ukrainian and Georgian membership, NATO thus provided Russian nationalists with evidence that the United States was seeking to “surround” Russia. (The 2016 NATO summit recommitted the alliance to the folly of prospective Georgian membership, even though few if any allies would be prepared to honor the resulting security commitment if Georgia were attacked.)

Matters came to a head in early 2014, when Ukraine’s president, Viktor Yanukovych, rejected a European Union association agreement in favor of economic support from Russia. In addition to popular resistance (the “Euromaidan” protests) that forced him to flee the country, the United States actively worked to install a prime minister, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, sympathetic to the West. Russia’s seizure of Crimea followed soon thereafter—whether provoked by U.S. actions or merely excused by them. Ironically, the U.S. intervention in Ukrainian politics (following Russia’s exercising its influence with Yanukovych) was more consequential than what Russia did in the 2016 U.S. elections. But global politics is littered with double standards. The problem arises when they get in the way of calculations about how to build relationships that have a chance of meeting the legitimate needs of all parties.

Russia’s seizure of Crimea, aggression elsewhere in Ukraine, and other pressures in Europe cannot be excused, nor its violation of formal agreements (the 1975 Helsinki Final Act and the 1994 Budapest Memorandum). Nor can Russian interference in the U.S. presidential election campaign be justified by the fact that the United States has itself for decades actively and regularly intervened in the politics and elections of dozens of countries around the globe. But the “Russia scandal” enveloping President Trump, however much he has contributed to it, is depriving the United States of the chance to explore whether there can be a true “reset” of relations with Russia, fully consonant with U.S. and Western interests.

Ironically, Donald Trump has shown a better understanding of the need for a new, mutually acceptable basis for relations with the Russian Federation than did either George W. Bush or Barack Obama. His valuable instinct, however, is now being buried beneath the fundamental debate about his presidency, which is feeding so much of the Russia scandal, in major part for U.S. domestic political reasons. In this context, the interests of the United States and the West are clearly losing out.