YOU CAN’T SOLVE A PROBLEM UNLESS YOU TALK ABOUT IT: A CONVERSATION ABOUT RACE WITH BEVERLY DANIEL TATUM ’75

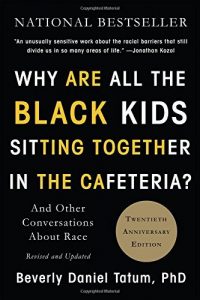

Beverly Daniel Tatum ‘75, Hon. ‘15, P’04, PhD, is a psychologist and author of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? and Other Conversations About Race (20th Anniversary Edition), (NY: Basic Books, 2017). She will be presenting a WESeminar based on her book on Friday, November 3, at 7 p.m., at the Wesleyan RJ Julia Bookstore at 413 Main Street in Middletown, as part of Homecoming/Family Weekend 2017. “I look forward to engaging members of the Wesleyan community in conversation,” says Tatum. “The Q&A is always my favorite part.”

The revised 20th-anniversary edition of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? has just been published. What inspired you to write the book in the first place? And what inspired the revision?

The revised 20th-anniversary edition of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? has just been published. What inspired you to write the book in the first place? And what inspired the revision?

Twenty years ago my goal in writing my book was to help others move beyond fear, anger and denial to a new understanding of what racism is, how it impacts all of us and ultimately what we can do about it. I wanted to inspire readers to break the silence about racism, and to use their spheres of influence to effect positive social change. I had been teaching about the psychology of racism for almost twenty years at that point and wanted to share what I had learned with a wider audience. Shortly after my book was published, I was on the stage with President Bill Clinton at a town hall meeting at the University of Akron—the launch of his Initiative on Race—and he explained that the time was right to work on the difficult issue of racism in American society because the nation was at peace and the economy was expanding. At that time, I shared President Clinton’s belief in the power of dialogue to help all of us move forward together in pursuit of racial equity and justice.

Twenty years later, I still believe in the power of dialogue. But today we are a nation at war, still suffering from the aftermath of the worst recession in modern history, disturbed by simmering racial resentments, documented racial injustices, and increasingly limited by a 140-character culture of communication. All of that makes meaningful racial dialogue more difficult, but also more necessary. My goal for the book remains the same as it was twenty years ago, but I was determined to bring the conversation into the 21st century.

More than 100 pages longer than the original edition, I begin with an analysis of the U.S. social and political context of the last 20 years, addressing issues such as the impact of changing demographics, persistent school and neighborhood segregation, the affirmative action backlash, the Great Recession of 2008, the election of Barack Obama and subsequent “post-racial” narratives, the emergence of Black Lives Matter and campus activism, and the early days of the Trump presidency—all in the context of contemporary race relations. Readers will find my answer to the title question remains unchanged, but the psychological research supporting it has been completely updated to reflect the current state of the literature, as well as an expanded consideration of the critical issues in the identity development of Latinx, Native, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Middle Eastern/North African, Muslim and multiracial youth, in recognition of the demographic diversity of the U.S. in the 21st century.

It has been 20 years since the book was first published. In your opinion, where have the biggest gains been made, and what have been the biggest missteps? And what has remained the same (for better or worse)?

The most diverse group of children in U.S. history will be taking their seats in classrooms across the country, reflecting the demographic shift rapidly taking place in our country. That diversity is a potential source of strength for the nation. However, despite the rising numbers of children of color, for the most part the schools they attend are more segregated than those their parents attended. More than 60 years after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, nationwide nearly 75 percent of Black students and 80 percent of Latinx students attend so-called majority-minority schools. Both Black and Latinx students are much more likely than White students to attend a school where 60 percent or more of their classmates are living in poverty. Separate remains unequal as schools with concentrated poverty and racial segregation are still more likely to have less-experienced teachers, high levels of teacher turnover, inadequate facilities, and fewer classroom resources.

A series of key Supreme Court decisions during the three decades between 1974 and 2007 dramatically reduced the number of implementation methods available to communities engaged in school desegregation by eliminating strategies such as cross-district busing, dismantling local court supervision of desegregation plans, and limiting use of race-based admissions to ensure diversity in magnet school programs. Students are, once again, predominantly assigned to public schools based on where they live, and to the extent that neighborhoods are segregated, the schools remain so. The persistence of residential segregation now ensures continuing school segregation.

The expansion of access to higher education offers a potential antidote to that persistent segregation. Colleges and universities are among the few places where people of different racial, cultural, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds can engage with each other in more than just a superficial way. However, because of both lack of direct contact and repeated exposure to cultural stereotypes while growing up, cross-group interactions can be uncomfortable. Even genuine efforts at friendship and connection can be derailed by awkward interactions and unconscious bias. Ideally, the college years offer a unique opportunity to engage with people whose life experiences and viewpoints are different than one’s own and to develop the leadership capacity needed to function effectively in a diverse, increasingly global, world. However, whether college students develop that capacity will depend in large part on whether the institution they attend has provided structures for those learning experiences to take place. Intentionality matters.

What surprised you the most, when thinking about that 20-year period? Are we where you thought we would be?

To me, the most surprising developments of the last 20 years have been the outcomes of the 2008 and 2016 presidential elections. The election of our first Black president, Barack Obama, conveyed a sense hope that America was moving beyond the racism so embedded in our culture. However, the backlash that followed his 2008 election, the increasing visibility of White supremacist activity during the 2016 campaign season and post-election, the assault on voting rights, the persistent racial inequities in the criminal justice system, and the polarizing rhetoric of Donald Trump all point to backward motion that I did not expect.

In those same 20 years, how has your perspective changed, if it has? Can you pinpoint experiences or events that affected that change?

When I wrote the first edition of the book, I was a faculty member. In 1998, a year after its publication, I became Dean of the College at Mount Holyoke, and in 2002 president of Spelman College. These experiences deepened my understanding of how much leadership matters. In my book I talk about why leadership matters, and what effective leaders do. Fundamentally, we know that human beings are not that different from other social animals. Not unlike wolves, we follow the leader. We’ve learned to categorize people as us or them. The process of categorization is innate but who we put into the various categories is not innate. We look to the leader to help us know who the “us” is and who the “them” is. The leader can define who is in and who is out. The leader can draw the circle narrowly, or widely. When the leader draws the circle in an exclusionary way, with the rhetoric of hostility, the sense of threat among the followers is heightened. When the rhetoric is expansive and inclusionary, the threat is reduced. As a leader myself, I came to understand how important it is to be intentional about what I call the ABCs—affirming identity, building a shared sense of community, and cultivating the leadership of others.

The subtitle of the book is: “and Other Conversations about Race.” Your use of the word “conversations” is intentional. Can you explain the importance of that word and its meaning to you, in your work?

I use the word “conversation” because I think it is important to talk to one another about the impact of racism in our society. Many people, regardless of racial background, avoid race-related conversations because they often generate discomfort—feelings of anger, sadness, fear, embarrassment, guilt, or shame are common. Yet, it is possible to get past that discomfort to have productive dialogue which can lead to feelings of empowerment and inspire positive action. One thing is clear: You can’t solve a problem without talking about it.

Knowing what you know, and having many years of experience and research to shape your opinions and outlook, outlook, as you look around today, what do you see in our future?

There is no question that we are living in a difficult time, and recent events in Charlottesville and elsewhere have been very disturbing. I work at maintaining my optimism because I believe that in times of darkness, we all need to generate more light. The epilogue in my book is titled “Signs of Hope, Sites of Progress” because I wanted to highlight places where positive things were happening. We all need to remember that each of us can exercise the kind of inclusive leadership we need to interrupt the cycle of racism. With the collective hard work and effort of many, I still believe positive social change is possible.