ALL THOSE MINDS LEFT BEHIND, BY JOSEPH J. FINS ’82, MD

From the headlines, it would be easy to think that the totality of health care policy is the fate of Obamacare, the threat posed by the opioid epidemic, and the scourge of gun violence. Throw in smoking and obesity and you have a pretty complete list. But you really don’t.

Health care policy (or what passes for it) deals with problems we recognize as important to the public health, access to care, or the threat of epidemics. But there are other topics that lurk on the periphery.

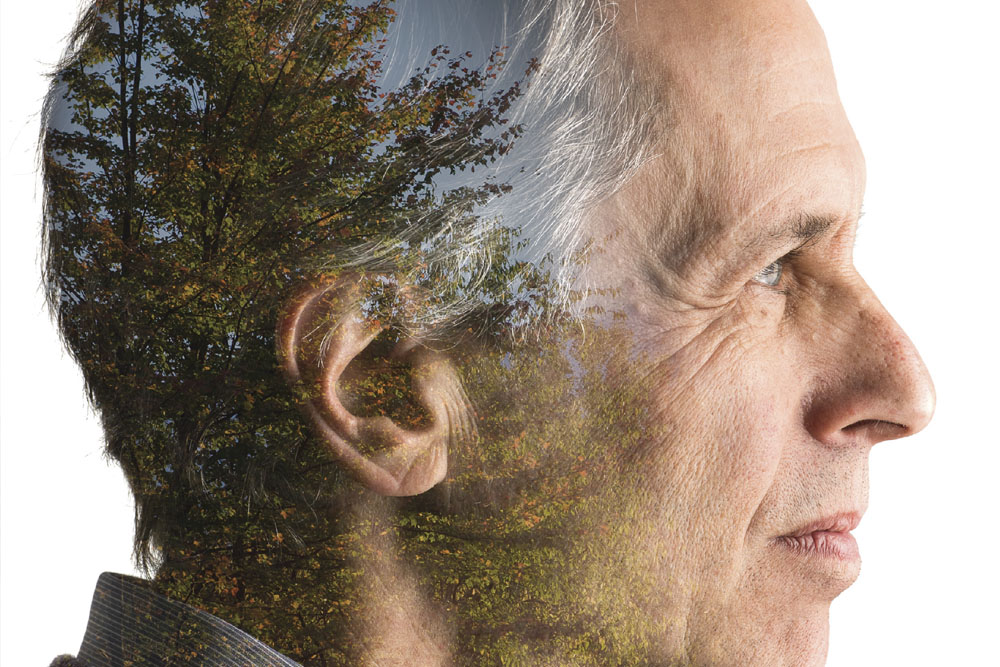

Perhaps befitting a Wesleyan alumnus who majored in the College of Letters and did premed on the side, I have lived on that periphery. For the last couple of decades as a physician and bioethicist, I have been thinking about what society owes people with severe brain injury, or more accurately, disorders of consciousness.

These patients come to national attention about once a decade under the guise of right-to-die cases.

In 1976, there was Karen Ann Quinlan, a woman in the persistent vegetative state whose ventilator was removed after her parents petitioned the New Jersey Supreme Court to let her die. In 1990, the Supreme Court of the United States heard the case of Nancy Beth Cruzan, another woman in the vegetative state whose family wanted to remove her feeding tube. Cruzan established a Constitutional right to refuse life-sustaining therapy and helped catalyze the use of advance directives. Most recently, in 2005 there was Terri Schiavo, another woman in the vegetative state, whose fate divided both her family and the nation, pitting patient choice against questions about the sanctity of life.

All these cases left an indelible mark on how we die, giving each of us more choice at life’s end. We can choose who represents us and help ensure that care decisions reflect our values and preferences. But this legacy comes with a paradox: The expansion of rights at life’s end has constricted rights for many patients with severe brain injury.

Consider the opinion of Chief Judge Richard J. Hughes of the New Jersey Supreme Court in Quinlan. He wrote that the state should not compel Ms. Quinlan to live without any “realistic possibility of returning to any semblance of cognitive or sapient life.” Because nothing could reverse her course, continued treatment was considered to be futile. It wouldn’t benefit her and only burden her family.

Over the ensuing decades, futility became the basis for a right to die. It also led to the neglect of patients with severe brain injury who were thought hopeless. Tragically, many patients who are saved by brilliant and costly acute care in the hospital are discharged and forgotten, left to linger in nursing homes receiving what is euphemistically described as “custodial care.”

One of these patients was Margaret (Maggie) Worthen, who is profiled in my book, Rights Come to Mind: Brain Injury, Ethics, and the Struggle for Consciousness (Cambridge University Press, 2015). Maggie Worthen was a college kid who, like us, had the privilege of going to a fine liberal arts college. She had the opportunity to do pretty much anything with her life. She majored in Spanish, loved Frisbee, and hoped to be a veterinarian; that is, until reading week of her senior year at Smith College when her friends heard some strange noises coming from her dorm room.

They tried to help, but Maggie was wedged against the door and they couldn’t get in. So an intrepid classmate climbed out through a window, entered a connecting room, and found Maggie unconscious on the floor. She was rushed to the hospital and found to have a bleed in her brain stem that extended up into her thalamus. She needed emergency neurosurgery to save her life and graduated in absentia while in a coma in the intensive care unit. At Commencement, her grief-stricken classmates wore blue ribbons in solidarity with their fallen friend.

I first met Maggie in 2008 when she came to the Consortium for the Advanced Study of Brain Injury (CASBI) at Weill Cornell Medical College and the Rockefeller University in New York to participate in scientific studies designed to elucidate mechanisms of recovery from severe brain injury. In tandem with the scientific studies of patients who come to CASBI, I conduct in-depth narrative interviews with their families to explore the ethical dimensions of care. To date, I have spoken with over 70 families who have shared their stories with me.

When Maggie came to New York, she was living in a nursing home and thought to be permanently unconscious, in the vegetative state. But her neurologist wasn’t sure, so her mother, Nancy, brought her to CASBI for studies.

The diagnostic question was whether Maggie was in the minimally conscious state (MCS). Unlike vegetative patients who are unconscious, MCS patients are liminally so. They demonstrate intention, attention, and memory. They may look up when you come in the room, grasp for a cup, or even say their name.

The challenge is that MCS patients demonstrate these behaviors episodically and unreliably, creating a staggering risk of misdiagnosis. Given the connection between brain injury, futility, and the right to die, most doctors are nihilistic about patients with severe brain injury. And they are skeptical when family reports of awareness are not reproduced. While a family’s observations may be a product of wishful thinking, the episodic behaviors seen in patients in MCS is part of its complex neurobiology.

In the aggregate, these factors lead to a staggering rate of misdiagnosis. One study found that 41 percent of patients with traumatic brain injury in nursing homes thought to be vegetative were actually minimally conscious. Imagine having a 4-in-10 chance of being thought unconscious when you are not? It is an especially frightening possibility when you are also unable to speak up to defend your own interests and are wholly dependent on the goodwill of others to know that you are there.

I vividly remember the moment when Nancy learned that her daughter was still in there. We had gathered at Maggie’s bedside for a neurological exam. Earlier in the day I had interviewed Nancy while Maggie underwent brain scans. In our conversation, Nancy shared a mother’s heartache about brain injury. She wasn’t quite ready to give up but wanted to know if Maggie was conscious. Did she know that Nancy was her mom? Could she possibly understand that she was loved?

Against this backdrop we stood at the bedside for the neuro exam. We had discovered that Maggie was sometimes able to answer yes/no questions by looking down with her left eye.

Normally a neurologist will hold up a pen and ask the patient if she sees a pen. But this time, my colleague—not knowing of my conversation with Nancy—asked Maggie to look down for yes if the woman at the end of the bed was her mom.

There was a pause. And then, she looked down. There was silence until Nancy gave me a huge bear hug and started to cry. I did not know if they were tears of sadness or joy but decided to just hang on.

Nancy was at once happy that her daughter’s brain could engage in “cognition” even as she was saddened by imagining Maggie’s isolation and future prospects.

As a physician investigator and medical ethicist, moments like these become the catalyst for both scientific discovery and health care reform. What can science do to find these hidden minds and give them voice? And once we know that people can be mistaken as vegetative, how do we protect conscious individuals from misdiagnosis and safeguard their rights?

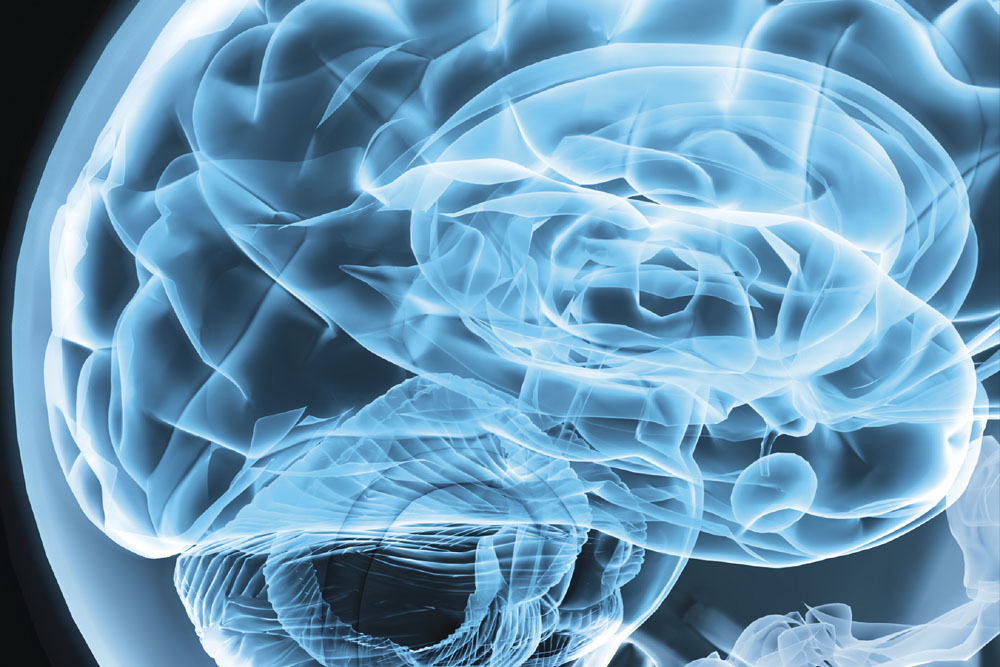

The science has really hinged on progress in neuroimaging. It has changed everything that I thought I knew about brain injury when I graduated from medical school more than 30 years ago. It has proven that our knowledge about consciousness is incomplete and contingent.

Now we can peer inside the injured brain and appreciate a discordance between behaviors and brain function. This is something we could not know before the advent of neuroimaging studies that contrasted what was observed at the bedside with what was seen on scans.

The protocol is elegant in its simplicity. Patients are placed in a scanner and asked to imagine doing a task that would activate motor, navigational, or linguistic areas in the brain. For example, they are asked to imagine playing tennis, walking around their house, or thinking about words with different meanings and similar pronunciations. When patients engage in these volitional activities, brain areas responsible for motor, spatial, and linguistic function light up.

In the absence of overt behaviors, these activations indicate cognitive motor dissociation and imply the presence of an underlying consciousness. Although the only consciousness we can truly know is our own, we can infer it in others when they hear a command, process it, and then mount a response. For most of us this is the expression of a behavior or a verbalization. For patients with cognitive-motor dissociation, their scans tell us they are there.

You might find this argument tedious and sigh or move on to the next article in this magazine. From either of these actions, I can infer your consciousness even if I am disappointed that I have not held your attention. Most critically, your actions serve as a proxy for your consciousness because they are internally driven and volitional.

When Maggie came to CASBI, she participated in neuroimaging studies that showed similar volition. Because she was a former swimmer, we modified the paradigm to have her imagine herself swimming. She was able to do this and also demonstrate other higher cognitive functions.

Beyond demonstrating brain function when none was presumed, neuroimaging has also demonstrated that recovery from brain injury is a dynamic process. Patients can get better and brain structure can change over time. In a 2016 paper in Science Translational Medicine, investigators from Weill Cornell Medicine showed structural changes in Maggie’s brain following her injury. Over a 54-month period, she rewired her brain with new white matter tracts across the two hemispheres and in Broca’s Area, the region central to language processing. These findings correlated with her improved ability to use an eye-tracker device to reliably communicate yes and no responses.

What is fascinating about this rewiring phenomenon, which appeared to underwrite her ability to communicate, is that it mimics the brain’s developmental process. Let me explain: Babies and children in normal development sprout and prune axons, the connections between neurons, in order to connect up the maturing brain and gain new functional milestones. The last part of the brain that gets “connected” in the late teenage years are the frontal lobes that confer executive function and judgment. This final step in brain maturation correlates with adulthood and the legal age of majority.

This same process seems to be recapitulated after severe brain injury in the service of repair. The re-harnessing of a developmental process to repair the injured brain is a new phenomenon in the history of human neurobiology. It is a function of new approaches to the early treatment of brain injury over the past few decades. Patients who would have otherwise died, now survive long enough to awaken dormant developmental mechanisms that now get repurposed to prompt recovery.

The ability to identify patients with cognitive-motor dissociation and to watch the injured brain recover over time has profound implications for health care policy. Now that we know that misdiagnosis occurs and recovery is possible, we cannot plead ignorance and look away. We need to identify patients who might be conscious but lingering in nursing home rooms alone in their heads. To invoke Lin-Manuel Miranda’s [’02] famous lyric from his musical Hamilton, even in their nursing home beds, they are in the room where it happens. To think otherwise is a tragic omission.

Just as important, when patients are mistakenly thought to be vegetative they are also presumed to be insensate; that is, unable to perceive pain. So misdiagnosed, patients who are not vegetative but minimally conscious might be subjected to medical procedures without pain medication. This is an egregious error that becomes all the more tragic when we recall that patients who are minimally conscious cannot communicate consistently and therefore cannot call out in pain. Given this, my first policy priority for this population is proper diagnosis and the provision of neuropalliative care to ensure adequate pain and symptom management. This is a basic minimum standard of care.

But there is more. If the injured brain uses a developmental mechanism to prompt repair, shouldn’t we recast rehabilitation as education? Society has cultivated primary and secondary education to accommodate the developing brain, appreciating that learning and progress take both a willing biological substrate and a substantial amount of time. If brains reengage the same process in the service of recovery, we need to rethink six-week courses of rehabilitation. It would be like sending your child to elementary school for a few weeks and then telling them they are on their own.

More fundamentally, we have to grapple as a society with the reality that we have segregated conscious individuals in chronic care and separated them from their homes, their families, and their futures. Over the past decade, I have argued that this constitutes a violation of both civil and disability rights, most notably the Americans with Disabilities Act, which mandates the maximal integration of people with disabilities into society. For patients with disorders of consciousness the challenge is not physical integration remedied by a sidewalk cut. Accessibility is achieved by giving patients like Maggie the means to express herself. By restoring functional communication we can help reintegrate these patients into society and rebuild community.

Overcoming the segregation of these patients is more than a health care policy issue. While access to care is critical, the challenge faced by these patients is more appropriately understood as a civil rights issue. After all, what other group remains as segregated as they are? Their plight isn’t even separate but equal. Their place in society is both separate and unequal, an intolerable comparison that begs for reform.

While it is too late for Maggie, who died in 2015, remarkable progress in rehabilitation, drugs, and neuroprosthetics—like deep brain stimulation and brain computer interfaces—is helping to make the reintegration of patients with severe brain injury possible. To my mind—and all those minds left behind—this can’t happen soon enough.

Joseph J. Fins ’82, MD, is the E. William Davis Jr.[’47 ]MD Professor of Medical Ethics and professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College; codirector of the Consortium for the Advanced Study of Brain Injury; and the Solomon Center Distinguished Scholar in Medicine, Bioethics and the Law at Yale Law School. Honored with a Distinguished Alumnus Award, Dr. Fins is a graduate of the College of Letters, former chair of the Alumni Association, and a trustee emeritus of the University. He has also served as the Kim-Frank Visiting Writer at Wesleyan.

Joseph J. Fins ’82, MD, is the E. William Davis Jr.[’47 ]MD Professor of Medical Ethics and professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College; codirector of the Consortium for the Advanced Study of Brain Injury; and the Solomon Center Distinguished Scholar in Medicine, Bioethics and the Law at Yale Law School. Honored with a Distinguished Alumnus Award, Dr. Fins is a graduate of the College of Letters, former chair of the Alumni Association, and a trustee emeritus of the University. He has also served as the Kim-Frank Visiting Writer at Wesleyan.