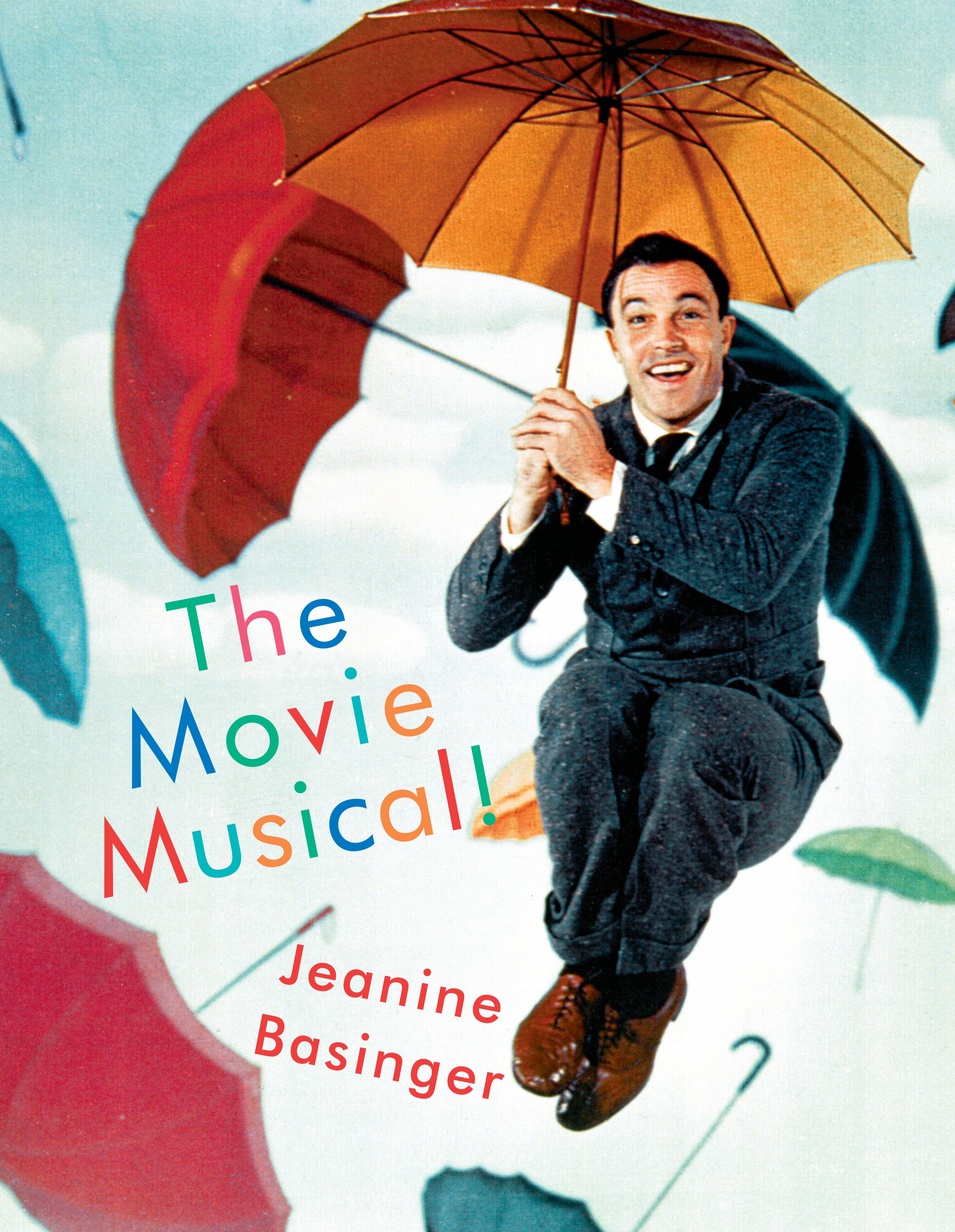

THE MOVIE MUSICAL! by Jeanine Basinger

In her new book (to be published this November by Alfred A. Knopf; excerpted below), Basinger tells the whole story of the Hollywood musical.

Fred Astaire, that most continental and debonair of men, was a quintessential American. He was born Freddie Austerlitz in Omaha, Nebraska, and everything that defined him can be seen as midwestern: hard work, integrity, ambition, loyalty, lack of pretension, and the ability to be sophisticated in the most natural way. When he began dancing in movies, there were few precedents for photographing dances imaginatively, except, of course, for Busby Berkeley’s methods, which wouldn’t work for a soloist like Astaire; yet he seemed to have an instinct for the camera, and he learned by doing. He was a perfectionist, and a quiet thinker, astute in his observations: “In the old days,” he said later in his life, “they used to cut up all the dances on the screen. In the middle of a sequence, they would show you a close-up of the actor’s face or his feet, insert trick angles taken from the floor, the ceiling, through lattice work or a maze of fancy shadows. The result was that the dance had no continuity. The audience was far more conscious of the camera than of the dance.” Astaire would not dance in movies if he could not control his own numbers—how they looked, how they sounded, and how they could be experienced. (“Either the camera will dance, or I will dance.”) His goal would always be the integrity of the performance. Astaire was not anti-cinema. He embraced such things as slow motion, travelling mattes, and special effects, but he wanted to dance in the center of the camera’s eye. That’s why Gene Kelly, himself an innovator of presenting dance on film, made the clear statement: “The history of dance on film begins with Astaire.”

Is there anything more lyrical than Fred Astaire, clad in a tuxedo, casually walking an English country road, swinging along through a misty, tree-lined world, hand in pocket, singing to himself? “A foggy day . . . in London town . . . had me low . . . had me down.” He twirls a bit, sings a bit, looks as if he’s on his way to play golf or do nothing, yet he’s duded up to the gills in a perfectly tailored tuxedo. He stops, sits on a fence in a softly swirling fog, and creates an intimate moment with the audience. He sings what’s in his heart, but ever so lightly, ever so casually, laying it on with ease and contained joy. He dances, too, but it’s his walk—that little sway from side to side, that tiny swing to his body, that one arm moving gracefully, rhythmically—that makes it all work, that makes it unique. He walks the way many great drummers walk—as if he’s responsible for the rhythm of life. A touch of class, a touch of Nebraska, and more than a touch of genius. For over five decades, that was Fred Astaire onscreen.

He was perfectly partnered by Ginger Rogers. They were both slender and the right height for each other. Astaire likes to move a woman rapidly around the floor in an intricate pattern of steps, and on a dance floor Rogers could fly. She was light and could be twirled up and around. She was flexible, especially in her remarkable back, which suited Astaire’s desire to have his female partner sway backwards and forwards from the waist up. She was very pretty but not so beautiful that she wiped him off the screen, and both could laugh with ease on camera. And, crucially, Rogers fit perfectly with Astaire in their dialogue scenes—they’re not great only when dancing with each other, they’re great when talking to each other. Their banter is like a musical number, with the same kind of pauses and checks and balances that their choreography has. Carefree, one of their minor movies (it has a loony plot, but great songs by Irving Berlin), demonstrates their skill at verbal choreography. Rogers, at the suggestion of her fiancé (the eternally, delightfully inadequate Ralph Bellamy), comes to see Astaire, who is for once not playing a dancer. He’s a psychiatrist (the kind we’re all looking for: a dancing psychiatrist). Rogers is willing to meet Astaire, but when she accidentally hears him refer to her as “dizzy, silly,” and “in need of a good spanking,” her mood changes. She will make it hard for him. (This is the traditional “meet cute” clash that marks the beginning of the onscreen Astaire/Rogers relationship.)

In a dialogue scene played in Astaire’s office, he directs her to a chair. She chooses another. He tries to redirect her. She refuses. He moves around the room in puzzlement. She holds her place. Their dialogue is a dance number: rat-a-tat, bump, rat-a-tat, bump. The two actors play the scene in a rhythm they’re both familiar with: back and forth, back and forth. He leads, she responds. He talks in a fluid line, and she challenges in return. To watch them work as actors is to see a musical pair who are completely inside each other’s timing, perfectly matched. They know each other’s moves both in dance and in dialogue, which is why they were a pair who became legendary in musical history. A wonderful secret always unfolds for the audience in a Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers movie. He’s just an ordinary guy, but suddenly for some reason, he will begin to dance, and then it happens. An audience can see he is beautiful, timelessly beautiful. She sees it, too. She begins to soften and glow and flow toward and into him, uplifted into her own realm of excellence by his attention. Astaire and Rogers were the promise that movies made to ordinary viewers: inside you, behind your looks, there is something else, something desirable and special and eternal. Like Fred and Ginger.