The Art & Science of Rhythm & Flow

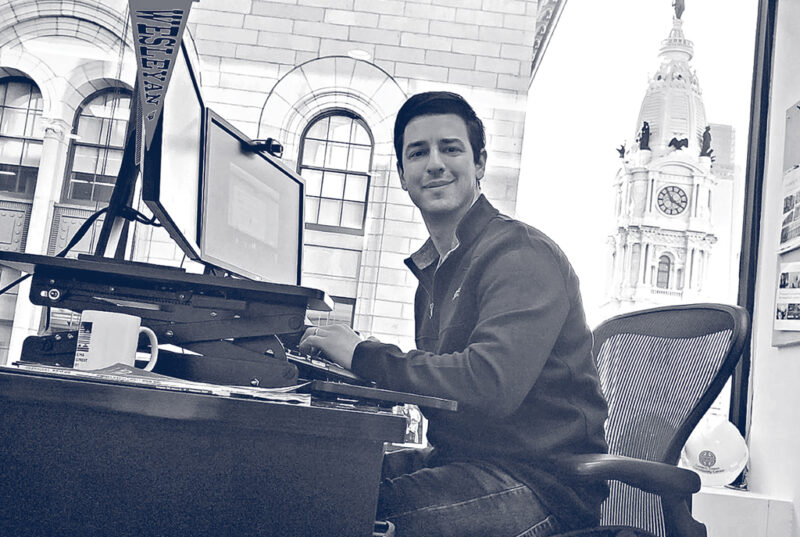

Freestyle Love Supreme cast members Kaila Mullady, Utkarsh Ambudkar, Anthony Veneziale ’98, Ashley Pérez Flanagan, and Aneesa Folds keep the energy pumping with on-the-fly rhymes and full-length musical numbers that culminate in a unique hip-hop improv theater experience. (Photo by Joan Marcus)

Anthony Veneziale ’98 steps up to center stage and invites the audience to share their “least favorite things.” Tomatoes! Bunions! College! Open seating in offices! The mild irritations and major ailments roll in and Veneziale’s companions pace the stage, indicating which topics they’ll take. The lights go down, a few solitary notes play, the beat drops . . . and the freestyling begins.

As the players (in this case Lin-Manuel Miranda ’02, Hon. ’15; Aneesa Folds; and Utkarsh Ambudkar) rap about the pains of unpaid loans and the agony of unkempt feet, you can feel the energy rising, the audience erupting into cheers and groans in concert with the rhymes, and, with a final mic-drop-worthy riff: CATHARSIS.

This is Freestyle Love Supreme, a transcendent mix of whip-fast wordplay, dope beats, angst-laden humor, and group therapy.

First conceived in 2003, when recent Wesleyan grads Veneziale, Miranda, and Thomas Kail ’99 were still just starting out, Freestyle Love Supreme was born in the basement of The Drama Book Shop in New York City, where Veneziale and Kail were running their own production company, Back House Productions, with fellow Wes alums Neil Stewart ’00 and John Buffalo Mailer ’00.

As Miranda remembered it on an episode of The Tonight Show: “We were working on In the Heights, it was my first musical. We had no money. I was a substitute teacher. . . . Anthony would come in and distract us, ‘Let’s rap about our day!’ . . . And we would just freestyle. And Anthony would be like, ‘We should do this in front of people!’ And here we are, 15 years later, on Broadway.”

From Background Player to Center Stage

But hold up. Rewind that back. Before the sold-out Broadway run and the all-star guests, even before the tight-knit group of Wes alums found their way to each other, Veneziale was just another sophomore looking to try something new at college.

“I got cut from the soccer team,” he says. “Two or three days later I auditioned for Gag Reflex.”

Joining Wesleyan’s oldest improv group may have started out as a way for Veneziale to fill his newfound free time, but it turned out to be an eye-opening education on community and creative voice, themes that would continue to play a prominent role throughout his life.

As the youngest of five boys in a big Italian family, Veneziale had grown up in an environment that put high value on seniority and the idea that the eldest held the most sway. Improv was the exact opposite of that. “When I got into Gag Reflex,” he explains, “the tables were completely turned as to what it meant to be a part of a family or a group. It wasn’t about seniority. Any good idea in the room was valuable, and whoever it came from, it was embraced. Yes, there were seniors in the group or ‘leaders,’ but they facilitated the experience. They didn’t dictate the experience. They informed and allowed us to find our own way, our own voice. And that to me was so spectacular. I was just so blown away by that sense of equilibrium and also the juice creatively that encourages.”

After graduating as a film studies major, Veneziale continued to perform, write, and produce with the aforementioned Back House Productions and on his own, helping to launch a reimagined Electric Company (featuring the rhymes of a pre-Hamilton Miranda) and continuing to develop Freestyle Love Supreme alongside other side gigs. But beyond the drive to create and perform, he also maintained an abiding fascination with the science behind improvisation and a persistent curiosity about the ways in which the performing arts can be used for so much more than just entertainment.

An Amazing Adaptogenic Tool

Doing his own research and drawing inspiration from many sources, including a book he read while studying Modern Dance at Wesleyan (Taking Root to Fly by Irene Dowd), Veneziale found connections between improv and the neurobiological activity that goes on in human brains when we push our bodies to explore space in new ways. He saw parallels in the way the brain forms preferred pathways and how getting out of patterns and habits can alter those synaptic connections. He wondered: Can improv be used as a kind of mental fitness regime to not only help with confidence and people feeling authentically themselves but also maintaining a healthy sense of neuroplasticity well into old age?

“It just proved to be such an amazing adaptogenic tool, this thing that is improv,” Veneziale explains. “It can be used in so many different interesting applications and the confidence gap is one of them. I really started to come into my own when I started doing improv. I felt the most authentically me. I felt the most heard, I felt the most seen. And I started thinking, ‘Am I an outlier? Is that something that is different about me?’ Did I have certain neural networks in my brain that set me up for success in that way? What is it about this pursuit of being okay with making mistakes and being okay with failing over and over and over again that might be useful?”

When Veneziale saw that a researcher he had been following, Dr. Charles Limb, was going to be moving to San Francisco where Veneziale now lived, it was an opportunity he couldn’t pass up. He cold-called the otolaryngologist to learn more about his work and see if there was some way that they could collaborate. Dr. Limb had gained renown for his research on brain activity during musical improvisation, putting jazz musicians into a Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) machine and tracking the different areas of the brain that are activated when improvising versus following a script or set piece of music. The timing was auspicious; Limb was on the verge of starting a new series of studies focusing on comedic improvisers and was looking for a partner.

Art and Science Meet in a New Kind of Improv

Veneziale’s company, Speechless, became a sponsor for Limb’s research and Veneziale himself (as well as many of his improv colleagues) participated in the study. It was a perfect pairing of science and art, as Veneziale had founded Speechless as a way to use improv workshops and science-based techniques to help people and companies (Google, Twitter, and Microsoft among them) to collaborate and communicate better.

“What we’re trying to really reinforce over and over again is that creativity comes in lots of different forms,” Veneziale says. “But it mostly comes from this part of your brain called the medial lateral prefrontal cortex. And that mostly gets engaged when you are playful and when you are vulnerable and when you have something called ‘psychological safety.’”

For Veneziale, that meant not only breaking down barriers around seniority and prescribed societal roles, but also setting the tone for people to feel that their voice mattered. In that way, Freestyle Love Supreme became a perfect vehicle to amplify different voices through a medium—rap—that was itself a response to the overwhelming frustration of not being heard.

“For me, this concept of where hip-hop and rap came from is really important because I’m a white man, and this is a black art form and it started in the Bronx. There’s a big part of rap that is about being disenfranchised: We are in this community, we are seeing these things and it doesn’t seem as though anything’s going to change. That’s the message that is a classic hip-hop song out of the Bronx: ‘Don’t. push. me. cause . . . I’m close to the edge.’ Right? And so Freestyle Love Supreme, in some way it was about the disenfranchisement of various perspectives inside of improv.”

As an improv performer in New York City in the early ’00s, Veneziale looked around and found that the people on stage overwhelmingly looked like him.

“It was 90% white dudes up on stage and I couldn’t help thinking to myself that that’s not why I got involved in theater,” Veneziale says. “I wanted to have multiple points of view on stage and then allow those points of view to flourish. So that at the end of it, there’s some sort of community that gets created afterward. I was really excited about this concept of: How can you help people create their own version of comedy? How can you help people create an environment where they are going to play to each other’s strengths?”

He made forming a diverse group of players a priority, gathering a tight-knit cohort of male and female rappers, beatboxers, musicians, and performers (the “Wu-Tang Clan of Improv” as one cast member called it), along with a rotating roster of surprise guests, including Miranda, Christopher Jackson, Daveed Diggs, Wayne Brady, and Bill Sherman ’02. True to Veneziale’s creative mission, the final, and arguably most important participants in the creative experiment were the everyday audience members who don’t just passively watch the show, but are equal partners in creating a unique communal theater experience every night.

“We have an improv show that is mostly this pretty fantastic language of rap and completely informed by the audience,” Veneziale says. “Everything we rap about is being generated there in front of these people in this moment so that they can feel it. They sense the authenticity and realness of that moment, just like in jazz. We have a little bit of the framework, but then the expression that happens inside of it is unique to the moment in which it was created.”

The Get Down and the Give-and-Take

That unique give-and-take, with the audience and performers joined in a heady, tongue-twisting hip-hop journey of risk and discovery, is part of what makes Freestyle Love Supreme more than just another improv show. Veneziale breaks it down to a blend of science and art, culminating in an experience that transcends ephemeral entertainment and aspires to more long-lasting benefits.

“The thing I love about our show,” says Veneziale, “is that you might come in thinking it’s going to be a comedy rap show. And then in the middle you’re probably going to cry. And then you’ll leave afterward and you can’t wait to talk to everyone about what you just saw.”

Two songs in particular hit an emotional and vulnerable chord. In “Second Chance” an audience member offers up a moment in their past where they experienced trauma. The performers re-create the moment in freestyle rap, including the negative repercussions that resulted from the event. They then rewind back to the same linchpin moment and this time retell it with a different decision and a different, positive outcome.

“When you do that kind of work, they’re retelling their stories, so they’re releasing the same chemical reaction in their brains as when they experienced it,” Veneziale says. “But then when we redo it for them, they actually rewire parts of their brain that have been adversely affected by that trauma. It reshapes their history in a way. After the show people come up to us and they’re like, ‘That was unbelievably cathartic.’ It’s mind-meltingly cool.”

The second song, “True,” calls for one of the cast members to reciprocate.

“‘True’ is where we take the lens and we put it on us,” Veneziale says. “We say, ‘Great, you’ve been really brave. You’ve told us some things about yourself. Now let us tell you something about us.’ So we get a word from the audience and it’s anything they want, any word they love. Then we rap a verse about a story that happened to us that is informed by that word. It really lets the audience see who we are. And we call it ‘True’ because the only contract we have is: You have to tell the truth in that moment. It gets pretty emotionally raw in there. And I think people have an experience of feeling like, Wow, this, this is really real. It’s really happening in this moment. And they are affected profoundly by it in a bunch of different ways.”

A Lifelong Pursuit of Experimentation and Growth

Ultimately, along with Freestyle Love Supreme and his ongoing work of amplifying different voices, Veneziale hopes to continue exploring the therapeutic and creative benefits of improv. And as his work with and grasp on the medium matures, he hopes to expand it to benefit a wider audience.

“There’s something about improv that really helps with beginner’s mindset,” Veneziale says. “And I would like to see as many people in the world using improvisational techniques to help them with creative endeavors, to help them be better versions of themselves, to be more mindful, and have the mental fitness to age gracefully and continue to learn. And that’s something that’s a lifelong pursuit. That’s something that you work on every single day.”

Freestyle Love Supreme ended its run on Broadway on January 12, 2020, but you can view performances on YouTube and in the original documentary We Are Freestyle Love Supreme, which premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival.