Citizen Artist: Creating Socially Engaged Theater as Civic Practice

Using experimental forms and immersive experiences, Assistant Professor of Theater Katie Pearl reimagines the relationship between actor and audience, creating socially engaged art and theater as civic practice.

The world is going topsy-turvy behind Katie Pearl’s head. Books and furniture whiz by in chaotic dips and turns. For a split second, it’s hard to tell what’s up and what’s down. We’re conducting a Zoom interview about her groundbreaking production of The Method Gun—itself performed entirely on Zoom—and Pearl is demonstrating how she and her student actors learned to translate the 3D live theater experience through a flat 2D medium.

“Part of what I needed to do was to be the instigator and cheerleader to get them out of this relationship of ‘Oh, now we’re sitting in our chairs acting in front of our cameras’—Unh unh! We have to like . . . [picks up the computer and moves it around wildly, creating a dizzying rush of movement onscreen]. We have to get up and go crazy!”

Finding inventive ways to reimagine the boundaries of live theater and the audience experience is nothing new to Pearl. A self-described director, playwright, and social practice artist, her aesthetic thrives at the intersection between dance, theater, the visual arts, and civic and social responsibility. Pearl acknowledges that this makes it difficult for some to categorize her art, and she offers “interdisciplinary theater” as an umbrella term for the various experimental, immersive, site-specific, and community-responsive work that she has done alongside traditional theater. At its root, however, she simply views it as “starting with a question and not limiting the form of the answer by traditional definitions of what theater is supposed to look like.”

Inviting the Audience into the Performance

In 2011, Pearl and her creative partner Lisa D’Amour (together as PearlDamour) collaborated with visual artist Shawn Hall to explore a basic technical question: What if we make a piece where what the audience is seeing is the process of making the piece?

Inspired by the devastation of Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill of 2010, the piece developed into How to Build a Forest, a contemplation on humanity’s intimate connection to the natural world: “How [we] live in it, rely on it, use it, and use it up.”

Over the course of the eight-hour performance, company members transformed an empty stage into a spectacular forest/deep sea landscape made primarily of fabric, wire, small-gauge steel, and repurposed found objects. For the first six hours, the stage is a quiet haven of focused activity with audience members welcome to interact with the forest throughout, either watching the build from their seats or taking a self-guided tour through it, even hanging out and observing the action from inside the forest itself. Once the “builders” have completed their work, the fully formed forest stays intact for exactly 30 minutes. During the final 90 minutes, the entire work is completely taken apart until nothing remains left onstage.

“It presents the question in terms of an environmental frame, but also a civic frame, reflecting how long it takes something to come into being—whether that’s a forest or a civic social system—and how quickly that can be undone and eradicated, whether it’s a work crew leveling a mountain top to get at the minerals within it or a government that undoes decades of social progress in a matter of months,” Pearl explains. “It gave the audience a quite profound experience of that kind of cycle.”

The experimental format of the piece—part visual art installation, part live theater—and inviting the audience to inhabit the performance helped set up what Pearl argues may be the most important part of the process: what happens after the show is over.

“How does it play out? How does it make change?” she asks. “Is it enough that when people leave the show they realize that they want to stop using plastic bags? Is that what we’re after? How do people take the intimate experience they had personally and move it into a larger sphere?”

Tough questions. And Pearl doesn’t necessarily have the answers. But while part of the goal is increasing awareness and providing an open artistic framework through which audience members can “see and experience for themselves in a way that’s unusual to day-to-day living,” Pearl and D’Amour weren’t content to just leave it at that. Their next project after How to Build a Forest would be among their most ambitious and far-reaching.

Bringing Artistry into Our Citizenry

Milton (2012–2017) took the civic-minded, audience-as-collaborators approach to a new level, tackling such fraught issues as race relations and what it means to be an American in five towns across America that share the same name: Milton, North Carolina; Milton, Massachusetts; Milton, Wisconsin; Milton, Louisiana; and Milton-Freewater, Oregon.

Pearl and D’Amour visited each town multiple times over the years. They got to know the different communities and connected with residents on a personal level, learned about their everyday routines, their personalities and points of pride, their community goals and aspirations, and the heavy weight of their communal histories and biases.

The intent wasn’t just to make a show for the community, but with the community, each one adapted to the town’s unique concerns. And to pair it with a collaborative project in an effort to promote civic engagement through art and set the stage for ongoing conversation and community togetherness. As they say in their book Milton: A Performance & Community Engagement Experiment, “Were the community projects context for the performance, or was the performance context for the projects? Yes and Yes.”

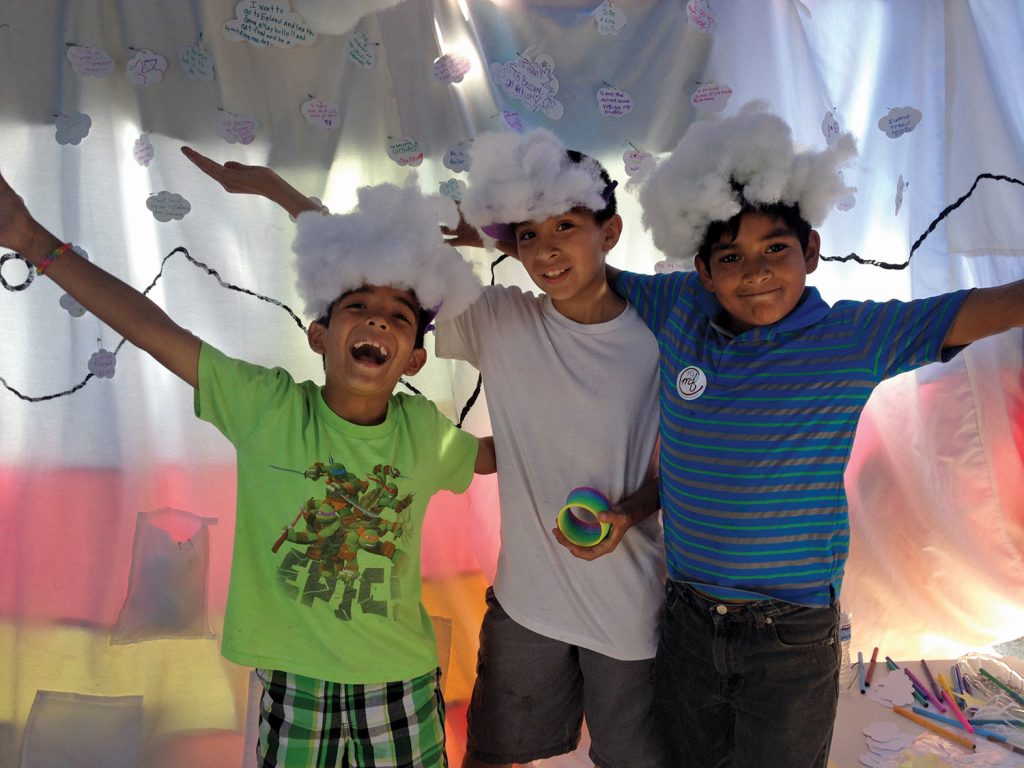

The resulting shows took place in common meeting sites such as churches, high school auditoriums, and the local library, and brought aspects of all five Miltons into one room: recognizable set pieces of each town’s landscape, artifacts from local businesses and residents, and recorded voices and anecdotes collected from their many visits. The larger-scale community collaborations took various shapes as well: an inaugural street fair in Milton, North Carolina, to help make the drive-through business district more of a destination and raise the profile and morale of the town; the Talk Play Dream – Hablar Jugar Soñar event series in Milton-Freewater, Oregon, to energize and promote the rich cultural offerings of the community and bring the almost 50/50 split between white, English speakers and Latinx Spanish speakers together; a “Milton Reflecting” program of yearlong activities to foster more consistent, creative opportunities to have nuanced, ongoing conversations about race in the wealthy Boston suburb of Milton, Massachusetts.

In this way, Pearl began to realize the power of creativity in social engagement, an ideal that she wrote about in an essay for HowlRound: “Our storytelling offers a different kind of narrative, driven by a different kind of energy—one that deepens thinking, expands empathy, introduces new worlds, explores imaginative possibilities, and rebuts current conditions. As theatre artists, our power doesn’t merely exist in the plays we create and the stories we tell. It also exists in our creativity itself. . . . How can we bring our artistry into our citizenry, rather than the other way around? How can our creative minds, our ability to make imaginative leaps, envision futures, and empathize and connect with others serve the communities that live outside of our theatremaking?”

It was a question that she had long been working toward, that was put into practice with Milton, and that echoed back to her again this past spring, when Pearl faced yet another weighty global concern and a new creative challenge emerged.

An Important Cultural Turning Point

In 2019, Pearl joined Wesleyan University as a new Assistant Professor of Theater. The artist who had made community such a central part of her work was now looking to join a more permanent community, both as a theater maker and as an educator.

Aside from teaching courses in acting, directing, and ensemble performance-making, Pearl was tasked with producing the department’s spring performance. She chose The Method Gun, a devised play by her longtime colleagues the Rude Mechs theater company in Austin, Texas. “Devised” plays are collectively created by a theater company as a whole (rather than one person writing a script and handing it off to the company to perform) and are usually so personalized that they rarely have a life outside of the originating company. But Pearl’s students had expressed a strong interest in devising and Pearl “wanted to bring something into the department that would let students take ownership in the making of the play the way that devising does.” She asked the Rude Mechs and received permission to redevise the play. In fact, the signed contract contains the line, “Katie Pearl can do whatever she wants with this production.”

With their blessing and the show cast, rehearsals began. But midway through the spring semester, just when Pearl and her students were “in that rich moment of ‘Wow, we’ve come together, we’re making this thing, we feel it . . .’” the University was shut down in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic and students were told to go home. It was a turning point for Pearl and the company: Should they abandon the live production now that there was no place to perform and social distancing mandates prevented the actors from being on campus together, much less in the same room?

In the end, the company decided (albeit begrudgingly) to pivot to the uncharted territory of Zoom. In reworking the play to fit the new format, the piece took on new meaning and became an exploration of a new line of creative questioning: What does it mean to make theater when you can no longer gather together in process or performance? How can one facilitate the intimacy of connection and interaction with the audience when every action and expression is filtered through the one-sided lens of a computer camera?

After grueling weeks of trial-and-error and daily challenges to rethink and reimagine the norms of live theater, the company performed two successful live Zoom performances to an audience of hundreds across the country and internationally. The response was overwhelming, as viewers (including members of the Rude Mechs themselves, professional artists, family members, and peers from other institutions) lauded the company for their innovative use of a software that was most commonly used for online meetings. Somehow, Pearl and her company of student actors and designers had overcome the limitations of the medium and created an intimate, interactive communal theater experience—complete with props that were “passed” between frames, a room-trashing brawl between two characters, and names that were gathered in real time from the audience and incorporated into a moving final sequence. All of this despite the fact that the actors were actually performing in isolation from their homes, separated from each other by thousands of miles and across four time zones.

What Is Theater Now?

Although she’s not eager to revisit Zoom any time soon, Pearl does see a shift coming in the way the arts community approaches theater, especially in light of the far-reaching impacts of COVID-19 and the current civic-social climate.

“I feel like the definitions of actor and audience need to change towards being part of a community that is using the creative moment to come together, to address a question, to investigate a shared experience, to dream, and to challenge situation,” Pearl says. “As we move into a post-COVID world, this is the direction that we have to go. Not only because sitting together in a packed theater with people is not going to be as viable, but also because the institutional models that support that kind of work are also really starting to be dismantled in terms of looking at the systemic racism that has been endemic to those institutions.”

As to how she sees herself continuing to move the conversation forward and evolving her art, on the professional side, PearlDamour is currently working on Ocean Filibuster, a musical performance that explores the “intimate, critical relationship between humans and the ocean.” On campus, Pearl is already looking ahead to the Theater Department’s upcoming Fall Production (which she will also direct).

“One thing I’ve been thinking about are large-scale community-engagement models like Public Works at the Public Theater—using a play as the technology to bring many different community groups into one performance, without homogenizing them. In a cool way, it can continue trying to answer the question posed by The Method Gun cast: What is theater now? I am really interested in how this model can translate to Wesleyan, and to see whether it can help shake up some of the systems that have traditionally made it difficult for certain individuals or groups to participate in department shows.”

Her plans are characteristically ambitious in scope, but with an eye firmly focused on a human scale and the power of connection, and fueled by a dash of optimism and a vision for a better world.

“A mentor of mine talks about how ‘our rehearsal rooms are where we can create our utopias,’” she says. “This is what I want community to look like. This is the world I want.”

For a behind-the-scenes look at the making of The Method Gun, see “The Method Gun: Producing Live Theater Online.”