Nietzsch Factor: Wesleyan’s First Ultimate Team

At Long Lane fields in spring 2022, Nietzsch Factor, Wesleyan’s open division ultimate team, began practice. Gaelin “Gaelo” Kingston ’22 curved a disc around Chase Yahn-Krafft ’25. Jack “Barnes” Noble ’25 whipped one behind his back to Noah Frato-Sweeney ’24. Some discs were left in the pizza bag bought off Amazon to be picked up by latecomers like Alexander “Zambo” Rubenstein ’25.

On the sidelines, Jonah “Six” “Peter” Yas ’25 poured one-third of a mason jar of almonds into his mouth. He spent a few minutes chewing, pacing. Before he had swallowed the first mouthful, he poured again. “Since I stopped eating meat I’ve had to eat so many nuts,” he explained.

The team was training for conference championships which had yet to be scheduled. They could be that upcoming weekend, or not. It’s a sport that abides by gravity but not bureaucracy, mostly.

Points are scored by catching the disc in the end zone, like football. Unlike football, there is more playing time than stoppage time. The player with the disc has limited time to throw and can’t run with it. So their teammates have to run around, thwarting the anticipations of the defense, and creating passing channels for themselves or their teammates.

Passing channels are like rivers. They are the lifeblood of ultimate and can be dredged anywhere throughout the field. And it’s not just the one river, it’s also the rivers that come after the first river. The more rivers ahead you are, the more your teammates are thinking of the same rivers, the more likely you are to win.

The World Flying Disc Federation (WFDF) records the first game of ultimate in 1968 at a high school in Maplewood, N.J. The original flying discs were tins from Frisbie Pies, a bakery in Bridgeport, Conn. Somewhere in the 20th century the packaging became entertainment for beachgoers and undergrads, as tins flew over Long Island Sound and college quads.

“Frisbee,” as a name for the toy and sport, was a copyright-wary derivative that WHAM-O adopted in the late 1950s. Eventually Frisbee was dropped from ultimate organizational names due to copyright concerns with WHAM-O, so—legally and colloquially—it is just “ultimate,” according to WFDF.

It’s a sport that abides by gravity but not bureaucracy, mostly.

Nietzsch Factor began as Wes-U-Bee. According to a website “created in HTML1 by hand,” as Scott “Scooter Mazhude” Michaud ’86 remembered his effort, the name changed in the early ’80s.

Dan Haar ’81—now a columnist and associate editor at Hearst Connecticut Media Group—wrote there: “The Nietzsch Factor was the speed of a guy named Nietzsch.… David Garfield ’80 looked less like an athlete than anyone . . . but he had NCAA Division I football speed, brilliant instincts, and great hands. . . . He hung around in the fall of 1980 before heading to Ghana in the Peace Corps.”

It wasn’t a reference to the German philosopher, but to the name of Garfield’s childhood dog, “Nietzsch.” In third grade Garfield had inherited the name himself.

The team name only changed after Garfield left for Ghana to finish his undergrad studies in African history—not for Peace Corps service. Garfield suggested that the change was prematurely in memoriam, his former teammates assuming he “was dying of malaria.”

As for the “factor” part, Steve “Moons” Mooney ’80 explained: “The ‘Nietzsch Factor’ was the [winning] difference.” About 15 yards of difference.

During games, Chris “World b” Heye ’81, P’14, Nick “Triggerman” Donohue ’81, and Mooney would throw long to Garfield who would go deep, fast. “All three of us were gluttons for glory,” said Mooney.

Donohue had been a high-school three-sport captain and spent much of his time growing up “throwing on the lamplit sidewalks of New York,” he said. “Hundreds of hours throwing at home meant some of us had ‘all the throws’—backhand, forehand, and overhead. This was a huge advantage at the time.” Haar said Garfield’s “non-athletic” look was part of the ploy because he would attract lesser defenders.

By Garfield’s own account, though, he wasn’t actually a remarkable player. He had begun only in college, without knowing how to properly throw. “I wouldn’t make the team now,” he said.

But back then, “ultimate was in its infancy. There was a concept of growing our skills together, communally, with no sense that we needed recognition. We just loved the sport.”

Wesleyan lists three ultimate teams now. While some women did play on Nietzsch Factor, in 1988 Lisa Brush ’89 founded Vicious Circles as a women’s team. The new team went on to compete at Nationals in 1990. “We had a super-cool team and the philosophy was: ‘Play everybody, value everybody, everybody who comes out is on the team,’” recalled Brush. “We didn’t have captains . . . We had WILPs—women in leadership positions.”

Vicious Circles now describes itself as open to “everyone who is not a cis-man.” The all-gender team, Throw Culture, begun in the fall of 1993, “strive[s] to keep things as inclusive and low-pressure as possible.”

Contemporary pros play under the American Ultimate Disc League (AUDL). AUDL has, since being established, vigorously created new rules. “They want big throws and a more interesting game to people who don’t know Frisbee, and that is very contentious,” Sam “Sephron” Ephron ’22 explained. Ephron is second-generation Nietzsch Factor: his father John ’86 was Michaud’s first-year roommate and then teammate. The younger Ephron understands the push for “sellability,” network exposure, and bigger audiences. He also said, “A lot of the really interesting parts of playing ultimate are the less interesting things to watch if you’re coming from a completely unaffiliated view.”

Donohue remembered earlier changes to the sport, to the disc itself. “The original disc was aerodynamically designed to turn over,” Donohue said. “When you would throw it, it would quickly reverse its arc and trail off. You would have to really put a lot of torque into it to keep it flying straight.” Donohue’s trick was throwing long, a strength he inherited from playing lacrosse. But when the new disc allowed everyone to throw long, he was disconcerted.

Mooney likened the issue to the change in surfing, from long boards to short boards: “There would always be people who were looking for the endless wave, even though there were short board competitions,” he said. Surfing survived that change; ultimate would survive too. The rules and the play were mutually informative. Sometimes the rules were ahead, sometimes behind, like how there was no real requirement on what it meant to be a college ultimate player before the mid-’80s, Michaud said.

UMass, Cornell, and other schools with graduate programs would have “what they euphemistically called ‘grad students,’ which were ultimate players who had graduated and were taking one course so they could continue to play college ultimate,” Michaud said.

That euphemism sometimes covered up to four years of “post-grad” play.

The categorical ban on referees has never changed. Players are expected to self-regulate, to not explicitly attack or foul their opponents. When they do, they might calmly return possession and restart. It is mostly successful. Donohue said that essence suggests a “humanistic approach,” as opposed to a “survivalist approach,” which he says is “known sport wide as ‘The Spirit of the Game.’” He adds, “This collaborative foundation is what makes ultimate what it is today: the ultimate sport.”

Nietzsch Factor currently abides by an ad-hoc rulebook which stopped being numbered after the 11th edition, Sam Harris ’23 said. Importantly, the document states “players are morally bound to abide by the rules.” In higher-stakes tournaments, there might be “observers,” but they only call boundary violations and points. For other violations, they have to be invited by the players to deliberate.

USAU has also been known to regulate uniforms. Harris said that at Nationals in 2013, officials made Nietzsch Factor change out of their “God is dead” uniforms. Three years later, they modified the design and permissibly returned with “God is dad.” They played at the National tournament in Norco, California, this past fall. Before games, in response to a player hollering “where am I,” Matt “Doug” Beetham ’22 said they would chant: “I am in a box/I am being rained on/I hate life/I was born to die.”

Alumni often continued to play. In Boston, Mooney, Donohue and Heye joined a Williams College crew to form The Rude Boys in a schism from Aerodisc, an established Beantown club. “The Rudies” won world championships in Sweden in 1983.

Michaud has been less active in the ultimate world. Instead, he’s been circulating in the international intelligence community.

One time, when traveling to Iraq, he got stuck in Kuwait because of paperwork backups.

“I was hanging out on a beach and there was this woman throwing a Frisbee with her friend. I asked to throw with them,” he recalled.

As military bureaucracy churned, he waited on a beach in Kuwait playing mini games of ultimate.

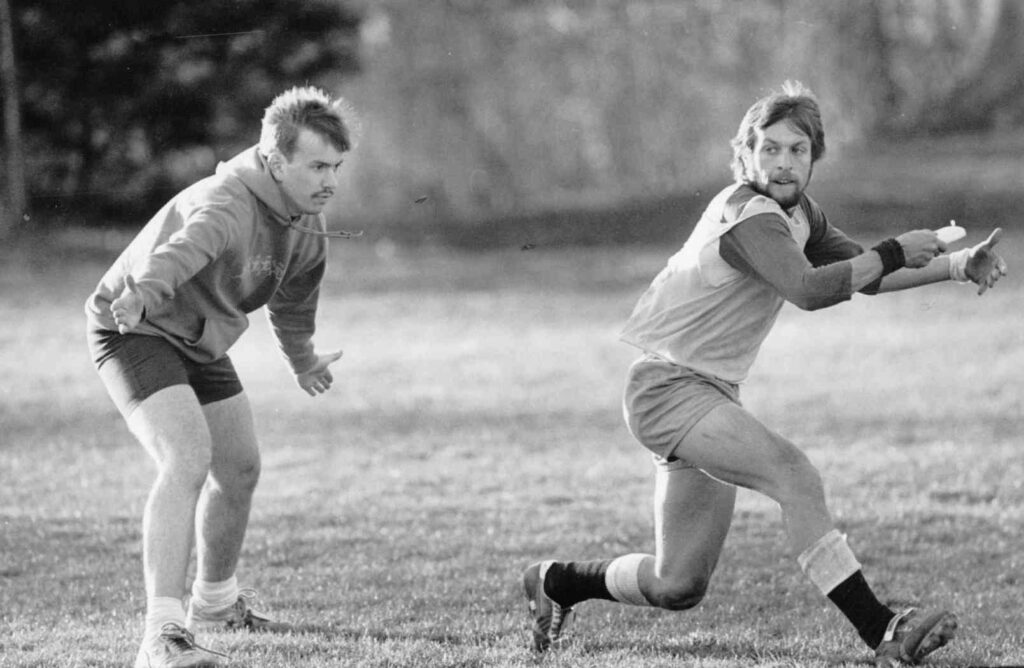

Top photo: Scott Michaud ’86 (front) and Jeff Staples ’84 (rear) also join the ultimate disc in a moment of flight.

By Maia Bronfman ’24