Freeing the Life of the Mind

Building on its legacy of leadership in prison education, Wesleyan’s Center for Prison Education opens doors to incarcerated learners through the liberal arts

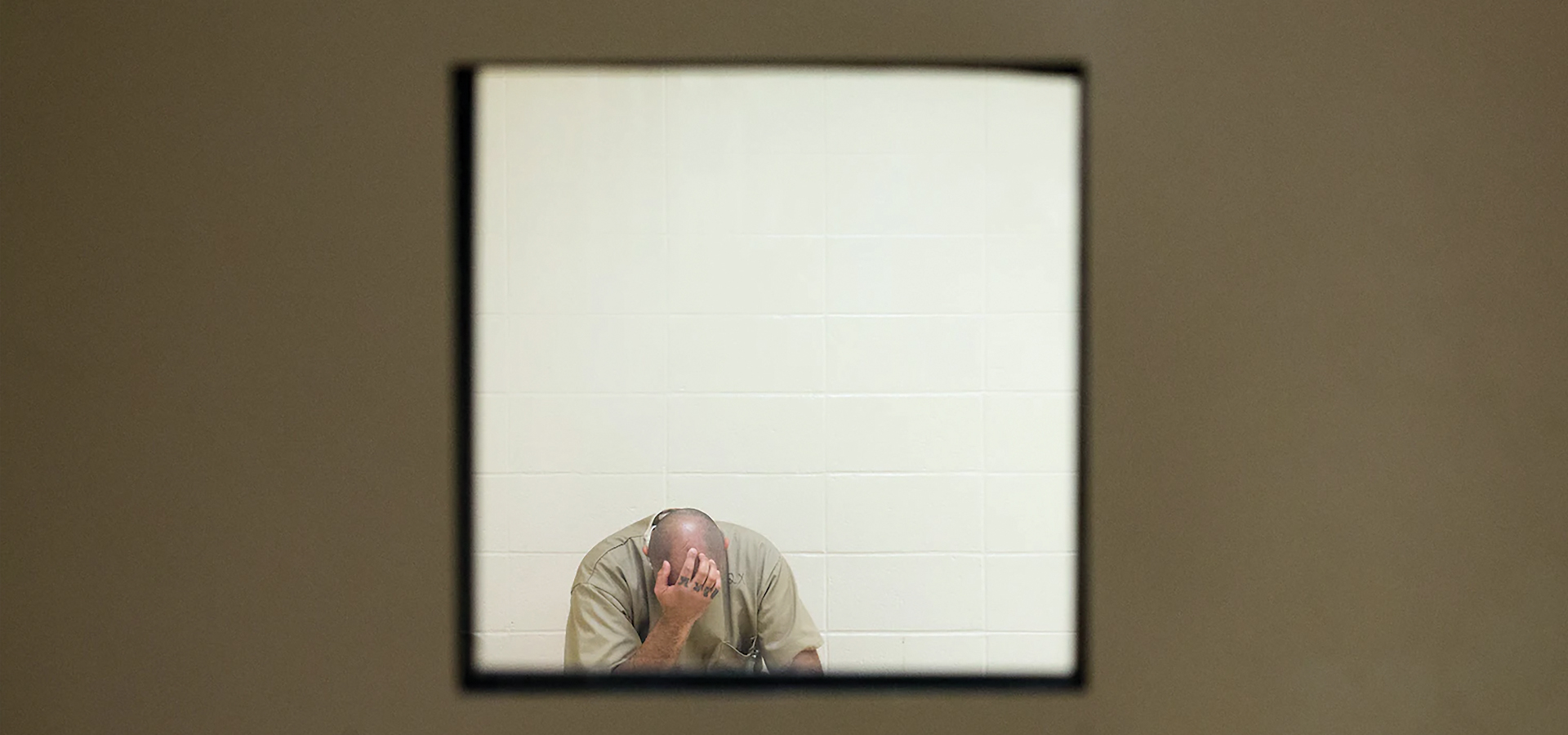

Prison is not an environment that’s meant for growth. It’s stagnant, airless for both mind and body. For people who have been incarcerated, it can be difficult to find opportunities for change.

Since its founding by students in 2009, Wesleyan’s Center for Prison Education (CPE) has been an agent of intellectual growth for hundreds of men and women in the Cheshire and York Correctional Institutions by providing access to a liberal arts education.

“I knew that education was key for me to be able to move forward. Without a college education or a degree in my hand, people would always just look at me as a felon. As an inmate. That is all that I would ever be,” said Marisol Garcia, a former student in CPE who returned home in 2019 and is in law school, where she is pursuing her interest in social justice issues.

Photographs by Christopher Capozziello. All rights reserved.

The degree Garcia earned was a General Studies associate’s in science degree, offered through CPE’s partnership with Connecticut State Community College (formerly Middlesex Community College). In 2019, the CPE took Wesleyan’s leadership in prison education one step further, creating a pathway to a Wesleyan bachelor’s degree for students inside. “We think that the [Bachelor of Liberal Studies Degree Program] will further the University’s commitment to enhancing inclusivity,” wrote then-Provost Joyce Jacobsen, in the proposal that the Education Policy Committee approved.

Then the pandemic struck, interrupting the forward momentum following that landmark development. A self-study and subsequent external evaluation conducted last year indicated work to do to build back enrollment and reestablish the program’s footing.

Enter Tess Wheelwright, the CPE’s first director, who joined the center in August 2023 from Freedom Reads, an initiative opening libraries in prisons and connecting incarcerated readers with literary communities.

“I have been welcomed with great energy from faculty, from the administration, from advisors, from students, from library colleagues, from the team. It’s a moment for CPE to build on its history and draw on its great superpower in terms of resources—its standout faculty—and move into leadership in the field as a center for bold and rigorous liberal learning in prison,” Wheelwright said.

Wheelwright first started in prison education while a graduate student at Cornell, but despite previous classroom experience, she had not taught adult learners. She found she loved the work, particularly seeing how students brought their own life experiences to the literature they were discussing.

“Expanding access to transformative learning has become the throughline of my professional life,” she said. “But maybe even more primary than that: the belief that people change, provided opportunity, and so the world can change.”

Wesleyan’s Center for Prison Education by the Numbers

- 2 locations, Cheshire and York

- 51 associate’s degrees conferred

- 15 Bachelor of Liberal Studies degrees conferred

- 66 Wesleyan professors have taught classes in the program

Cheshire Correctional Institution

- Established in 2009

- 102 courses offered

- 122 students taught

York Correctional Institution

- Established in 2013

- 35 courses offered

- 53 students taught

Among those aiding Wheelwright’s period of discovery is Shirley Sullivan ’21, CPE’s program coordinator. Sullivan’s commitment, staying on even after graduation to help create a Wesleyan experience at these locations, is a powerful continuation of the initial impetus that led students to begin the program. “It is our job to replicate the Wesleyan campus learning experience as best we can, imagining our way around the challenges of the context,” Sullivan said on a panel during Homecoming Family Weekend.

Other contributors to Wheelwright’s initial planning process include Jennifer Mayo Curran, director of Continuing Studies and Graduate Liberal Studies; Clifton Watson, director of the Jewett Center for Community Partnerships; and three CPE alumni, including Garcia. Strategic goals for the years ahead include the development of an alumni engagement program to support students in the translation of CPE learning into their post-prison educational and working lives.

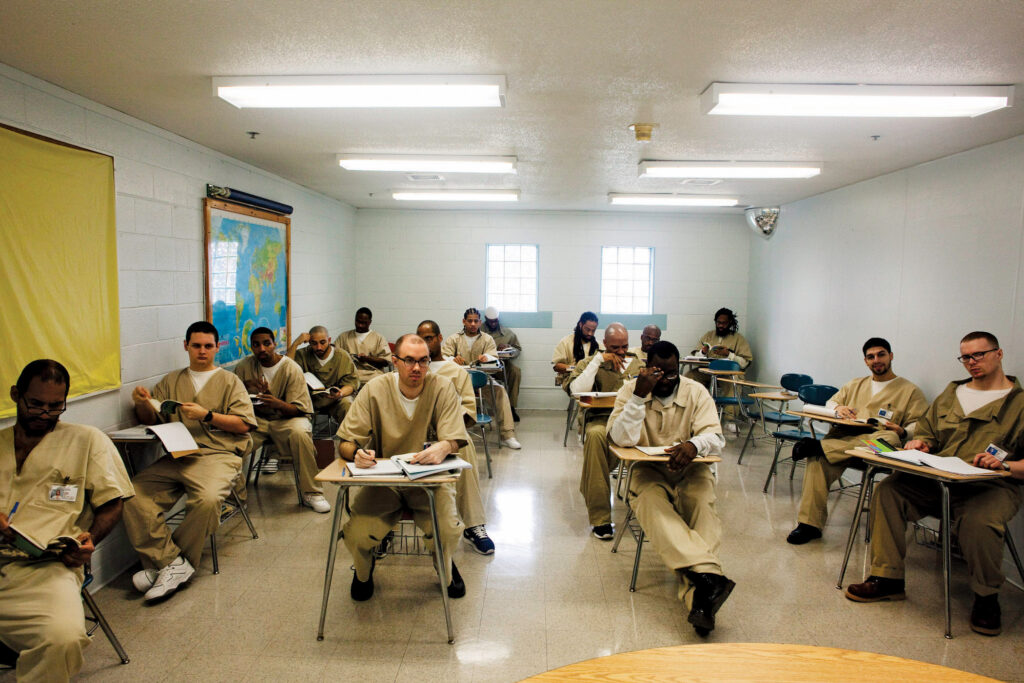

The central goal will always be for students at Cheshire and York to receive the same education a student on Wesleyan’s campus would receive. CPE students possess the same appetite for bold inquiry and the same commitment to challenging themselves and taking intellectual risks, their professors say. Of course, there will be differences—the classroom experience isn’t, and can’t be, precisely the same.

The door to the classroom is guarded. Students only have access to computers on a limited schedule, and their laptops are entirely non-networked. Typed assignments are carried out by CPE staff on USB drives for third-party delivery to professors back on campus. There are delays to doing research; scholarly articles searched in offline indexes must be tracked down and printed by campus volunteers, then delivered back to incarcerated researchers days later.

They must transition from the coldness of their governed circumstance to the warmth of the classroom—which can be a jarring back-and-forth. “I want to acknowledge the pain I put in while writing this paper. Inside prison, we use the phrase ‘putting in pain’ when we see the extreme concentration, dedication, sacrifice and mental and emotional anguish someone is suffering through because they are striving on a project as if their life depends on it. I’ve put in more pain than I can believe,” wrote CPE student David Heywood in his prize-winning philosophy thesis.

“The students are prepared. . . . You’d better read everything you assigned inside and out to prepare for class because they’ve read it all. They come in with deep questions. They have a hunger for learning that demands the best of us.”

Professor Tony Hatch

When the system works and the ideas are flowing, the CPE classroom is alive.

“The students are prepared. . . . You’d better read everything you assigned inside and out to prepare for class because they’ve read it all. They’ve discussed it. They’ve connected it to other stuff they’ve read. They come in with deep questions. They have a hunger for learning that demands the best of us,” said Professor of Science in Society Anthony Ryan Hatch, who has both taught in the program and been part of the Faculty Advisory Committee.

“My very deep belief is that nobody is defined in terms of the worst thing they did. Nobody is defined by their upbringing or their circumstances. We are always changing and one really exciting way that change can happen is through education,” said Lori Gruen, professor of philosophy and one of the founding faculty members of CPE.

Garcia’s adjustment from prison to the outside was, in her word, accelerated. She holds a couple of jobs on top of her legal studies, while also balancing internships, fellowships, and policy work.

Studying with CPE was Garcia’s entry to a life of the mind. It was her chance to feel, for a short period of time, “normal.” She felt the classroom was the only place she was able to voice her opinions, to be able to share who she was before prison. “You know, there comes a point in your life when you are dealing with the cycle of incarceration when you get tired of people telling you who you are and what you are,” Garcia said.

There were moments when she wasn’t sure the classes would work for her—she didn’t understand how the reproductive health class connected with the economics class. “I didn’t think a liberal education was going to prepare me for what I needed. However, it did because I have the ability to think outside the box and to apply certain things [I learned],” Garcia said.

Garcia’s research delves into mental health and the stigma of mass incarceration—ideas she started exploring with Wesleyan professors while at York. It acts as the groundwork she hopes to build on in a PhD dissertation after law school, she said.

For J. (name withheld for privacy), it was an introductory course in environmental science that helped push him in a new direction. “I started thinking about how I can live my life in a way that’s friendly to the environment, healthy for me, and healthy for others,” J. said.

His mother had a small garden when he was growing up, so when he left and with the lessons of the course ringing in his ears, J. started a small garden, which led to a job at a plant nursery and more work with a local farmer. He now sells the vegetables he grows as part of a local collective, taking the theoretical concerns presented in a CPE classroom to the tangible world.

“(CPE) gave me a reason to wake up in the morning. It gave me a group of people with whom to associate myself, people who were on point and focused about what they were doing. We were serious about trying to better ourselves, so that when we got out of prison we would have a life,” J. said.

In addition to improving operations and raising the increased budget CPE needs to grow, part of Wheelwright’s charge is to help CPE students feel like a bigger part of the Wesleyan community after they leave prison.

Professor Hatch recalled a moment when he reunited on campus with a student from his CPE Sociology of Knowledge course who had just returned home from prison. “I gave him a little embrace,” Hatch said. “We exchanged numbers. ‘Hey, hit me up if you need it.’ I was able to offer some support down the line where it was needed, just a little nudge along the way. That exchange, among the thousands of students I’ve taught over the years, was special because here he was free.”

“I am grateful to be part of this project to empower people . . . through opportunities for intellectual exchange and college community-building, to imagine and claim new possibilities for their lives.”

CPE DIRECTOR TESS WHEELWRIGHT

A new cohort of 14 students at York were admitted in January for the Spring 2024 semester, selected by a faculty committee for their promise and enthusiasm about the liberal arts opportunity. In the summer of 2024 at Cheshire, 22 students who completed their degrees during COVID will walk in an overdue graduation ceremony.

Said Wheelwright, “I am grateful to be part of this project to empower people through wide-ranging and rigorous course offerings, through opportunities for intellectual exchange and college-community building, to imagine and claim new possibilities for their lives.”

SAMPLING OF COURSES OFFERED

- Intro to the Nervous System

- Politics, Morality, Emotion

- The Art of the Personal Essay

- International Organization

- Biology of Women

- History of Political Philosophy

- Vectors and Matrices

- Sociology of Knowledge

- Performing Shakespeare

- Discrete Mathematics

- Gender/Nation/Subjectivity