A Hard Life, Well Lived

Professor Christina Crosby’s life as a cyclist, faculty chair, and able-bodied person was brought to a devastating halt following a harrowing 2003 crash. In rebuilding her life and momentum, she produced some of her finest scholarship and helped found an entirely new field of study. But she would have been the first to admit that hers is not a traditional redemption story.

By Christine Foster

As Christina Crosby lay severely injured in a hospital bed after a catastrophic bicycling injury, one of the first things the Wesleyan professor requested was for her partner, Janet Jakobsen, to read aloud from a favorite book, George Eliot’s Middlemarch. Crosby was not one to run from the tough stuff—she wrote unabashedly about both sexual pleasure and about managing bowel movements. In her memoir, A Body, Undone: Living On After Great Pain, Crosby explained that what she needed in that moment in 2003 was “no heavy handed forecasting, or ‘if only’ regrets.”

Crosby’s story, which seems almost cut short following her unexpected death of pancreatic cancer on January 5, was a remarkable one, both before and after the accident that left her paralyzed. Yet her friends and colleagues say she would have balked at the simplistic narrative that so often is pasted onto stories like hers—where the heroine suffers a tragedy, then rises, making headway that wouldn’t have been possible without the tragedy.

“I think progress is a fraught concept and one that Christina would have pushed back on a lot, and in solidarity and agreement I will also push back on it,” says Sally Bachner, an associate professor of English, a longtime friend whose office was across the hall from Crosby’s. “She was a Victorianist, and was deeply critical of [Victorian] structures of thought. I think she would have talked about her own progress in terms of the resources that were at her disposal. She was aware of the outpouring of support that she received from [the Wesleyan community], and even more so of her tireless partner, who worked on her behalf. That meant that she had access to resources that supported her in being able to make progress. She worked hard, but always with an awareness that she did so within a particular structure of access to health care, to caregivers, to material support, to communal support.”

Before the Crash

From early in her life, Christina Crosby’s story defied traditional narratives. Raised in a conservative small town in Pennsylvania, she made headway as an undergraduate at Swarthmore College in the 1970s, where she helped found Swarthmore Gay Liberation. At Brown University, where she earned a PhD in 1982, Crosby served as a leader in a feminist caucus that took on domestic violence, helping found a women’s shelter called Sojourner House. (One of the first in the United States, it has served more than 50,000 since 1976.)

In 1982 Crosby headed to Wesleyan, where she eventually become a professor of English and feminist, gender, and sexuality studies (FGSS), and spent the rest of her career. When she first arrived, women’s studies, as it was then known, was a nascent collection of course offerings, not yet recognized as a major program. For the next four decades, Crosby was an anchor for the program, serving as coordinator and chair of the program in its early years, and as an advocate for the transition to the name FGSS. Crosby helped the program to secure its first autonomous faculty line. In the late 1980s through 1999, Crosby routinely taught half of the program’s core classes. Over the last 21 years—including the two years she was away from teaching after her accident—she taught about a third of the core courses. The department now cross-lists classes across all three divisions and offers a full-fledged interdisciplinary major. “Christina’s dedication to FGSS carved out a space for critical thinking about sex and gender at Wesleyan—for faculty, students, and staff,” says Jennifer Tucker, the chair of the program.

It was at Wesleyan in 1997 that Crosby met another brilliant feminist, Janet Jakobsen, a professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Barnard, who was a visiting scholar at the Center for the Humanities. The women became partners (Crosby would always write “lovers”), and for the first six years they enjoyed a beautiful life split between New York and Middletown, including a favorite memory Crosby shared in her book of a joyous night out in bootcut red leather pants. Jakobsen would remain steadfastly at Crosby’s side throughout the rest of her life—for better or worse, in health and in sickness.

Pivotal Moment

On October 1, 2003, Crosby was at a high point in her life—just past her 50th birthday, she had been elected by her colleagues to serve as chair of the faculty, and was preparing for meetings with Wesleyan trustees the next day. Her personal life was also at a climax. “In the years just before I broke my neck, I was deeply happy,” Crosby wrote. “I was joyfully engaged with my lover, delighting in her body and in my own.” Additional passions included “riding my gorgeous Triumph motorcycle,” “making a peach pie in August,” reveling in her “well-defined muscles.”

As she crested a hill on her bicycle, three miles into her usual 17-mile route in the crisp, mid-fall air, her life changed in an instant. A branch lodged itself between her spokes, throwing Crosby headlong over her handlebars and slamming chin first into the pavement. The impact was so strong, the pavement so hard, it broke two vertebrae and left her unable to use her arms or legs. In time, Crosby regained limited mobility in her hands and arms, allowing her to continue her trademark enthusiastic gesturing when she spoke and taught. But the damage was done. In a single moment, she became trapped in a body that no longer did her bidding.

The road back to even part-time teaching, two years after her accident, was long and excruciatingly painful. Her perspective, always thoughtful and nuanced, had expanded, taken on a new lens. Given her own unique background, as well as her investment in scholarship that often sought to question the status quo and expected narratives, Crosby was in a unique position to assess her disability from all angles. This included pushing back against reclamation or redemption narratives, as well as against cultural structures and norms that favor those with able bodies. Three years after her accident, Crosby introduced a new FGSS course called “Ethics of Embodiment,” applying feminist and queer theory to perspectives on how bodies matter.

In 2016, Crosby’s work in this arena expanded beyond Wesleyan when A Body, Undone was published. Raw and honest, it weaves together Crosby’s profound gift for understanding and using language with her insistence on authenticity. It has become a new classic in the young field of disability studies. In 2018 the book was unanimously selected as Wesleyan University’s First Year Matters Program common reading choice. A review in The New Yorker describes her contribution to the field this way: “Crosby resists both self-pity and the too-easy narrative of hardship overcome. Instead, she asks readers to recognize how messy, precarious, and queer, in every sense of the word, life in a body can be.”

“I think Christina was more interested in who is left out of those narratives of progress and how do we understand their successes or achievements,” says Natasha Korda, the director of the Center for the Humanities, a professor of English, and a member of the FGSS faculty. “One thing that our culture might tell us is you just have to have a backup plan or something, or ‘man up.’ . . . After giving a reading of an early draft of the book, somebody in the audience (who I believe was also in a wheelchair) was basically suggesting to her that she just needed to man up. I think that the courage manifested by her book is not that of simply enacting or performing a kind of inspirational theater: ‘This happened to me, but I overcame it.’ It maybe has more to do with talking about the experience in a very frank and straightforward and courageous way that would make a life that is not ordinarily visible to other people, visible to them.”

One way Crosby embodied this visibility was by simply living. In returning to teach again after the accident, her presence itself forced changes, both physical and philosophical. In the Center for the Humanities, the University expanded doorways and created an accessible bathroom so Crosby and others who use wheelchairs could have basic access to the space. She also became an advocate for those, like her friend Bachner, whose disabilities (chronic migraines, an inflammatory autoimmune disease, and advanced spinal degeneration) are less outwardly visible.

A Teacher First

While Crosby’s book contributed to the new field of disability studies, perhaps the biggest impact of her work is to be found in the generations of students she taught. Abigail Boggs ’02 and Laura Grappo ’01, for example, went on to teach alongside her at Wesleyan. Another, Maggie Nelson ’94, is a renowned author who has written often about Crosby (and Crosby about her).

“I think that A Body, Undone is in part beloved and important as a book because it very actively doesn’t treat disability as something to be overcome and to come out the other side of a stronger, better, more spiritually enlightened person per se,” says Nelson. “One of Christina’s many, many great virtues, and why she was such a good friend and why we will all miss her so much, is she was more able to stay present in an ambivalent moment than anybody I’ve ever met, and more able to bear witness to the many complexities moving through any given moment. There would be no simple idea of progress for her. She was intensely alive to pleasure and positivity and rigor and change and optimism and political radicalism in all kinds of things, as well as justice and empathy. She just was committed to the complex.”

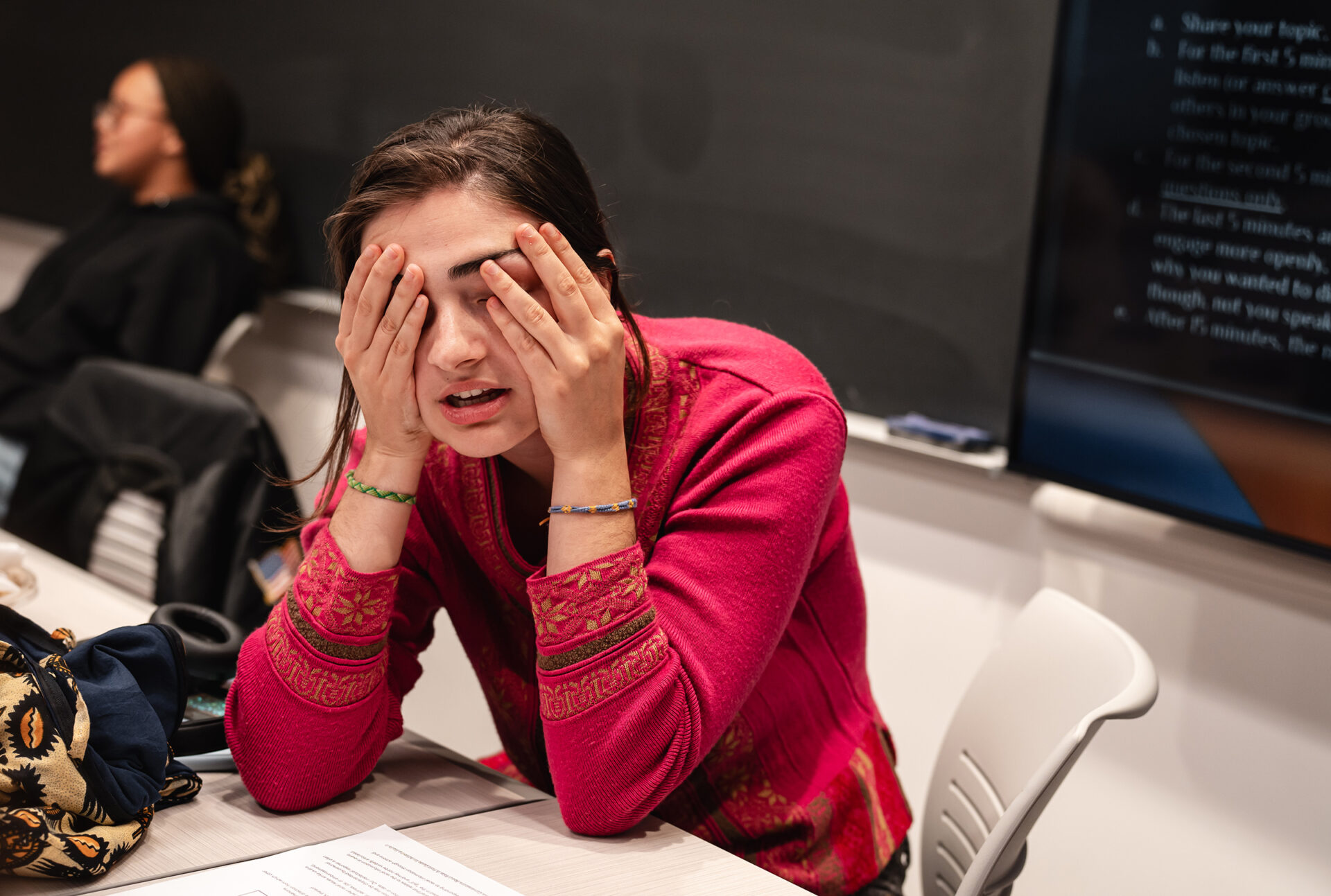

One of Crosby’s last students, Zuzu Tadeushuk ’21, came to Wesleyan specifically seeking Crosby’s mentorship. Tadeushuk, a former model, was drawn by Crosby’s work on the idea of embodiment.

“She always came to meetings with so much to say and having deep thoughts about what I was working on, which felt surprising and really generous to me,” Tadeushuk said. “My thesis is a memoir of my years working in the fashion industry. Sometimes when Christina would summarize my experience back to me, I would see new things in it that I hadn’t seen for myself. That was the main gift that she gave to me—just her attention and her attentiveness helped me learn for myself, helped me to learn from her.”

A Life Undone

This spring was to have been Crosby’s final semester teaching before retiring. But even then, she wasn’t content to maintain the status quo. Jakobsen recalls Crosby entirely rewriting the syllabus for her feminist theory class over the summer to bring the Black Lives Matter movement to the fore.

“It was about addressing the most pressing issues,” Jakobsen said. “She rewrote it, made it very fresh. It actually felt like a class that was very of-the-moment and that was pushing the field forward, pushing Christina’s teaching forward, and hopefully pushing the students forward, too.”

That rewritten course would be her coda. In late December 2020, heading into that final semester of teaching, Crosby went to the hospital with a bladder infection and was diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer. She would only live days more. Some in Crosby’s position would have focused on those “if only” regrets. If only she missed that branch. If only she lived to see Tadeushuk’s thesis finished. If only she had the chance to maneuver her wheelchair through a widened doorway into the Center for the Humanities just one more time to hear those final tributes at the end of her last semester of teaching.

Yet, in the midst of her deepest pain earlier in life, Crosby chose Middlemarch. She embraced complexity and nuance. She never lost her unbridled enthusiasm for a party and good conversation and still remembered what it was like to revel in those sexy tight red leather pants. She listened intently and pushed students and colleagues into a deeper understanding. May Wesleyan go forth to do likewise.

Photos courtesy Janet Jakobsen unless otherwise noted

* * *

Sidebar: Professor Christina Crosby’s Lasting Legacy

“Instead of treating me as someone who was less disabled than she was, she was super aware of so called ‘invisible disabilities’ that nobody can see, in part because she experienced so much invisible pain. She used to say, ‘you have pain, like I do.’”

—Sally Bachner, Associate Professor of English

“Christina was serious about scholarship and serious about fun. She had a great sense of humor and was so much fun to work with on student events. I remember a year when FGSS students came to the annual senior presentations dressed as their senior thesis projects and other students had to guess what they worked on. She was witty, and she made us laugh. Whether it was organizing events or discussing a student’s research project, I feel so grateful to have worked alongside her.”

—Jennifer Tucker, Associate Professor of History and Feminist, Gender and Sexuality Studies Program Chair

“I find myself most trying to emulate Christina in how I deal with my own students—just try to treat people with decency, with kindness. When you’re a grad student and you’re a younger professor, I think a lot of folks think that to be taken seriously, especially as a woman, you have to be so strict and cold and that sort of thing, but I think what I really learned from Christina is that that’s not necessary. If you walk the walk, then you can be open and kind and helpful and not have to do that. For me, that was a good thing to see. I’m really trying as I go forward, and especially right now when people’s lives are just so chaotic and crazy, to rely on my better nature.”

—Laura Grappo ’01, Assistant Professor of American Studies