THREAT ASSESSMENTS

BY GABRIEL POPKIN ’03

White House Situation Room, May 1, 2011, 4:00 P.M. EDT: Presiden Barack Obama and his inner circle anxiously watch aerial footage of one of the highest-stakes and riskiest operations ever carried out—a team of elite Navy SEALs raiding a fortified compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. The leaders back in Washington don’t know for certain whether their target—terrorist leader Osama bin Laden—is actually in the bunker that President Obama has just sent the SEALs into. They also don’t know if the troops will make it out alive. It’s a moment that will forever after define a presidency.

White House Situation Room, May 1, 2011, 4:00 P.M. EDT: Presiden Barack Obama and his inner circle anxiously watch aerial footage of one of the highest-stakes and riskiest operations ever carried out—a team of elite Navy SEALs raiding a fortified compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. The leaders back in Washington don’t know for certain whether their target—terrorist leader Osama bin Laden—is actually in the bunker that President Obama has just sent the SEALs into. They also don’t know if the troops will make it out alive. It’s a moment that will forever after define a presidency.

You probably didn’t notice Nick Rasmussen’s right shoulder peeking out from behind John Brennan, President Obama’s assistant for homeland security and counterterrorism, in the famous photo from that tense evening. But in another photo, now framed on Rasmussen’s wall in the director’s office at the National Counterterrorism Center in McLean, Va., he is shown briefing President Barack Obama while the nation’s top political and national security figures—Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, and CIA director Leon Panetta, among others—listen intently.

Rasmussen has staked out an increasingly influential position at the center of the nation’s counterterrorism conversation since the 9/11 attacks thrust the issue into the forefront of American consciousness. His assessments of the intelligence on bin Laden’s whereabouts contributed to one of President Obama’s biggest foreign policy successes. He has helped break down barriers between intelligence agencies that obscured a full picture of Al Qaeda’s operations and points out that no such mass-casualty attack by a foreign terrorist organization has occurred in the United States in the more-than-15 years since. He is now helping to modernize the country’s counterterrorism arsenal yet again, to counter emerging threats from nimble, Web-savvy organizations such as ISIS.

Most remarkably, friends and colleagues say, he has done this high-level work with an almost unparalleled degree of self-effacement, competence, and nonpartisanship. Rasmussen’s reputation for providing superb analysis and advice and remaining calm under pressure has led to his serving under three presidents, through two political-party transitions, and has elevated him to the nation’s top counterterrorism post, from which he seems to command universal respect.

“He’s not a person of any pretension or bravado or anything like that,” says Martha Crenshaw, a terrorism expert at Stanford University who taught at Wesleyan from 1974 to 2007. “He’s someone who wants to get the job done and done well, and who’s concerned about the mission.”

“I can’t imagine anyone I would trust more, given the issues he has to address,” says Jonathan Schwartz ’87, cofounder and CEO of CareZone, a tech company that helps people manage their families’ health care, who has known Rasmussen since they roomed together at Wesleyan. “He has a fantastic mind with an unparalleled capacity to really understand all the nuances and be able to come to a conclusion that likely saves lives and prevents things from happening that no one will ever know about.”

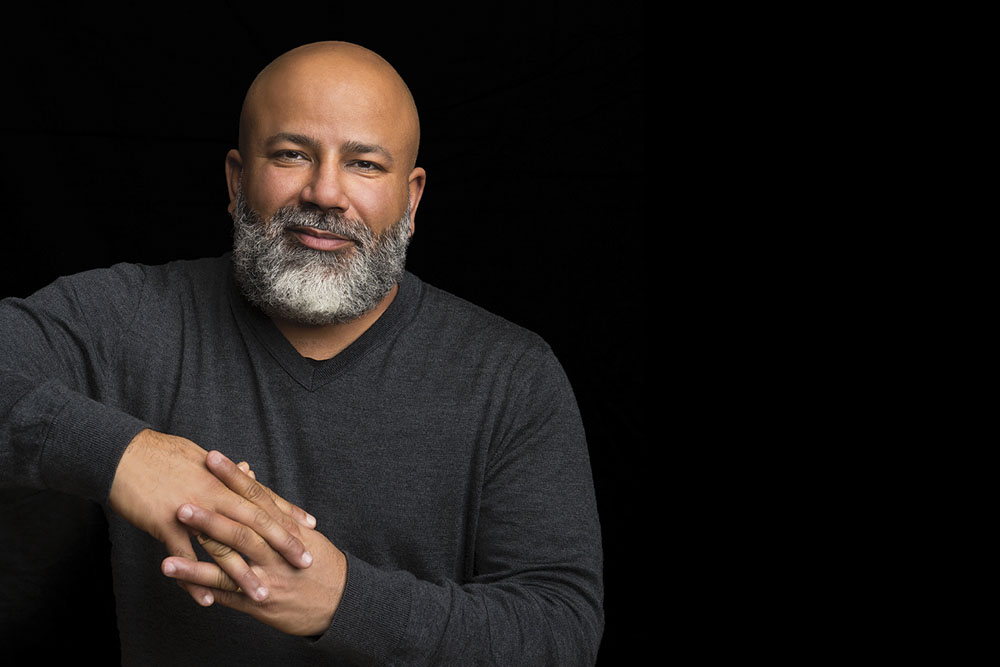

Nick Rasmussen sports a neatly trimmed, greying goatee and an intense, penetrating stare. Despite this imposing exterior, friends and co-workers describe him as a congenial colleague, a passionate fan of D.C.-area sports teams, and a gifted mentor dedicated to keeping his fellow Americans safe.

Rasmussen had his sights set on government from an early age. He was born in 1965 and grew up in the D.C. suburb of Fairfax, Va. His father worked in the Department of Education, eventually becoming its senior-most civil servant; his mother was a teacher in the Fairfax County school system. One of his brothers joined the military and has served multiple tours in Afghanistan.

At Wesleyan he gravitated to the College of Social Studies (CSS), famous for its intense interdisciplinary curriculum merging history, government, economics, and social theory. There, he says he learned to synthesize vast amounts of material quickly, build persuasive arguments, and express himself clearly and persuasively—and grammatically. “I still can’t split an infinitive,” he says. More seriously, he adds, “I draw on the training I got from that core curriculum literally every day.”

Friends recall his smarts, his studiousness, and his efficiency at digesting large quantities of assigned readings and producing weekly papers that propelled him to the top of his class. While Thursday nights found many students banging out essays on dorm-room electric typewriters well into the wee hours of Friday morning, Rasmussen typically had his assignments wrapped up by mid-afternoon Thursday, before many had even started, recalls fellow CSS-er Tilden Katz ’87, who now works at the firm FTI Consulting in Chicago. “Nick was the cleanest, clearest writer.”

Professors agreed. “His essays showed an ability to think insightfully and organize the ideas clearly, gracefully, and at times dramatically,” CSS professor Nancy Schwartz wrote in an evaluation. “He can think analytically and strategically, and enjoys doing so.” Schwartz recalls that “he cared about world politics and had good judgment about how nation-states deal with each other and emerging situations.”

Though set on a career in government, Rasmussen arrived at Wesleyan without knowing how he would pursue his goal. He was turned on to foreign policy during a course taught by former U.S. ambassador to Tanzania John Shirley, who was a diplomat in residence at Wesleyan at the time. During his junior year, Rasmussen interned for a semester in the Department of Defense Asian Affairs Office, and he was hooked for life. “It was very seductive,” he says. “It was important stuff—it was exactly what I wanted to be doing.”

After picking up a master’s degree in public and international affairs at Princeton, Rasmussen interned and then worked as a foreign affairs analyst in the State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs. His first job included negotiating for U.S. forces’ access and basing in Middle Eastern countries following the first Gulf War, which ended in 1991. From 1994 to 1996 he supported the U.S.–North Korea Agreed Framework, which slowed down North Korea’s nuclear program for almost a decade. He then spent five years working on the Arab–Israeli peace process.

In late summer of 2001, Rasmussen accepted a job as director for Regional Affairs in the Office of Combating Terrorism in President George W. Bush’s National Security Council (NSC). Six days before he was due to start, terrorists linked to the Al Qaeda network carried out the deadliest attacks on U.S. soil since Pearl Harbor, killing nearly 3,000 people. To many U.S. security officials, the 9/11 attacks provided a powerful dose of humility: They had let down a country that had counted on its government to detect and thwart such threats.

The attacks also injected an additional urgency to their work: Many in the government believed that other major attacks were being planned. During the months after 9/11, Rasmussen’s office staff tripled in size to around 15 people, and its workload expanded proportionately. He facilitated nearly 100 meetings, which collectively formed what he calls “almost a continual conversation” about Al Qaeda and the region of the world it was operating from.

FROM POST-9/11 DISCUSSIONS EMERGED A CONSENSUS TO CREATE AN INFORMATION HUB WITH ACCESS TO ALL INTELLIGENCE, WHETHER THAT INTELLIGENCE IS COLLECTED OVERSEAS OR HERE AT HOME.

“No matter the pressure, Nick was always composed and focused on the task at hand,” recalls Michele Malvesti, who worked with Rasmussen at the NSC and is now a professor of practice in international security studies at Tufts University. Even when others might let emotions overtake reason, she says, “Nick was able to be deliberative; he was always able to calmly evaluate both sides of any argument.”

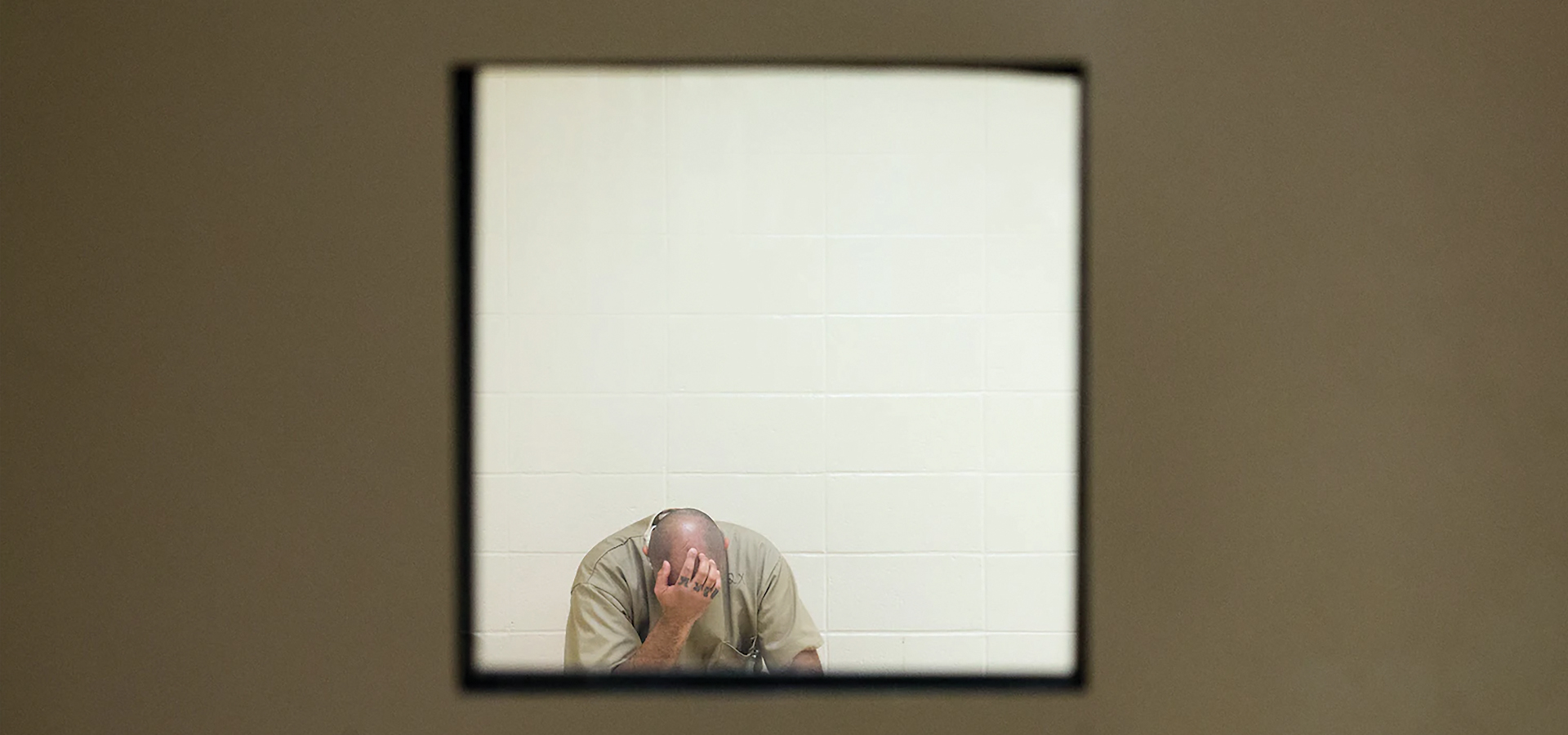

From post-9/11 discussions emerged a consensus to create an information hub with access to all intelligence, whether that intelligence is collected overseas or here at home. The National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) was born, and Rasmussen took a job there in 2004, producing assessments of U.S. counterterrorism policy and strategy for President Bush and the NSC. Rasmussen describes the agency as an “honest broker,” with the goal of helping others make decisions. He and his colleagues take in and fuse information and intelligence from the CIA, FBI, the Pentagon, and other agencies, and brief top officials, often including the president. The heart of the center is a high-tech “operations room” where analysts watch banks of computer and TV monitors through which information from around the world pours in.

QUIET AMERICAN HERO

Rasumussen speaks to CNN’s Jim Scuitto in the NCTC Ops Center, but he generally keeps a low media profile.

The intelligence community has been criticized at times for not sufficiently synthesizing this information. But by reducing what Rasmussen calls “stove-piping”—a tendency for information at one agency to not mix with that held by another agency—he says the NCTC has given intelligence professionals the access they need to help thwart sophisticated planning operations before they reach action stage. “We’ve made tremendous progress in our ability to detect and prevent a multi-actor, catastrophic attack like 9/11.”

In October 2007, Rasmussen rejoined the NSC. When President Obama took office in 2009, he chose to keep Rasmussen on—a testament, colleagues say, to Rasmussen’s professionalism and ability to work with and gain the trust of colleagues. “Rasmussen’s ability to remain in close proximity to two Presidents [now three, as the current administration has kept him on as NCTC director] … is a tribute to his deep substantive knowledge, cool temperament, and the fact that he is not a politico but a reliable professional,” wrote former Princeton classmate John Sivolella, now a political science professor at Columbia University, who called Rasmussen “a quiet American hero.”

The NSC role put Rasmussen at the center of the discussion leading up to the bin Laden operation. He and others spent months trying to determine how likely it was that bin Laden was in the compound and the risk to the lives of U.S. forces sent in to take him out. As the picture became clearer, Rasmussen repeatedly briefed President Obama and senior staff, while keeping anyone who didn’t need to be in on the conversation out of it— which, he wrote in a recent reflection, led to some “very uncomfortable moments” with colleagues. He also recalled 38 anxiety-filled minutes as around 20 of the country’s top officials waited in the Situation Room to learn whether the operation was successful. They saw one of the raid’s helicopters crash, but once the SEALs entered the compound, they had no information on the operation’s success until it was over. “It’s a scene you never forget,” Rasmussen wrote.

The scene also reflects another key to Rasmussen’s approach to counterterrorism: the importance of teams. “He’s somebody who is entirely built around teamwork,” says Audrey Tomason, an officer at the National Intelligence Council who worked under Rasmussen at the NSC (and who is indirectly responsible for Rasmussen not appearing in the famous photo— he says he had positioned himself so that she could get a better view). “Nick is someone who really builds teams around him and empowers those teams to do their best work.”

Tomason also notes the importance Rasmussen places on managing the stress of working in such a high-pressure field, breaking up long workdays with group lunches and keeping televised sports games on in the background when immediate threats force staffers to work over weekends. He and his wife, Maria, travel when they can, including to the Philippines, her home country. But he admits that in his job, “you never totally check out.”

The year after the bin Laden operation, Rasmussen left the White House and took the deputy director job at NCTC. When the agency’s director left in 2014, President Obama nominated Rasmussen to replace him. As director, Rasmussen spends less time directly analyzing intelligence, focusing more on synthesizing and communicating the work of hundreds or even thousands of analysts at his agency and others. “Often I end up being the spokesperson for a very large intelligence community, presenting our integrated view of the terrorism threat environment.”

The threat environment he has found himself facing differs starkly from the one he encountered during his first stint at NCTC. While Al Qaeda remains a primary counterterrorism concern, the group calling itself the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, commonly known as ISIL or ISIS, has taken center stage and operates from a completely different playbook. Rather than have a centralized leadership plan sophisticated attacks, ISIS recruits potential terrorists via the Internet and encourages radicalized people in Western countries to carry out “lone wolf ” shootings and bombings of the kind that have become all too common: San Bernardino, Paris, Manchester. ISIS strategy has dramatically shortened what Rasmussen calls the “time from flash to bang”—the time from when a person is radicalized to when that person carries out an attack. This compressed timeline has presented steep challenges to the counterterrorism community, Rasmussen says. A 2016 NPR profile of Rasmussen described the situation: “Counterterrorism Chief Sees Gains on the Battlefield, Stubborn Threats at Home.”

But Rasmussen and his team have also adapted to the new reality. They consider traditional sources of intelligence as well as the vast expanse of publicly available information, including social media. To supplement human analysis, they are experimenting with advanced computational techniques known as machine learning to comb vast quantities of data for meaningful patterns. They work with social media companies to identify how terrorists are using their platforms and what new methods they are using for dissemination. They also work with communities to help them identify the signs of radicalization. Still, he says, determining what information is relevant is a perpetual challenge. “It’s not just a haystack; it’s a mountain of haystacks,” he says. “We can’t hire enough analysts; technology also has to be part of the equation.”

Rasmussen and his colleagues continue to look for ways to share and aggregate more information—always moving “toward a more perfect union,” he says— and have built collaborations with partners around the globe facing similar threats.

Nevertheless, Rasmussen admits that he and his colleagues don’t have all the answers. After Omar Mateen killed 49 people and wounded 53 at an Orlando nightclub in 2016, Rasmussen and others pored over intelligence they had received but could not identify what they could have done differently to identify the threat. In another recent interview, he named two worries that keep him awake at night: the possibility of a shadow terrorist network escaping detection inside the U.S. and the continued challenge of keeping weapons off the thousands of airplanes that fly every day.

“I come at the job with a lot of humility,” he says. “My humility has grown over time. There are no easy fixes.”

As he accepted a Distinguished Alumnus award at Wesleyan’s 2017 Reunion and Commencement Weekend, however, Rasmussen sounded a more hopeful note. “There is no doubt that the world today is more challenging and more dangerous,” he told fellow alumni. “But I would also argue that we have more capacity to defend ourselves—more capacity to keep ourselves safe—than we have ever had before.”