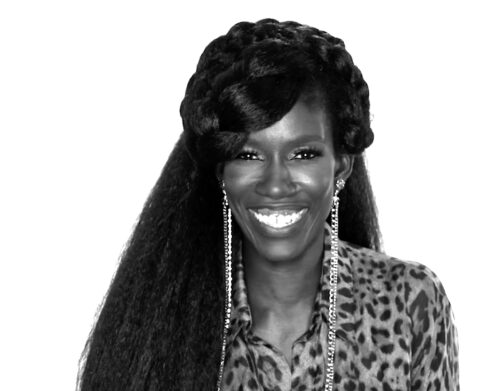

Men in the Machine: Playwright Haymon ’16 Explores Kafka in Contemporary America

(Photo of Miranda Haymon ’16 by Jejomar Ysit ’19.)

This September 5–17, at The Tank in New York City, Miranda Haymon ’16 directed In the Penal Colony, her theatrical adaptation of Franz Kafka’s short story. Broadway World described the work as “investigat[ing] the performance of power, patriarchy, and punishment.” Critic Darryl Reilly of Theater Scene wrote, “Brilliantly realized … a symbolic exploration of race in the United States. It’s a jolting blend of dance, movement, and physical theater dynamically performed by an African-American cast.” He called Haymon’s staging “electric,” and her adaptation “pared down yet faithful.”

Haymon, a German studies and theater double major when she was at Wesleyan, notes that both brought to bear in this production. Working with set designer Tekla Monson ’18, lighting designer Zack Lobel ’19, sound designer Anthony Dean ’17, associate producer Rose Beth Johnson-Brown ’18 and stage managers Veronica Harrington ’17 and Lex Spirtes ’17, she is quick to call the production “very Wesleyan” and gratefully notes the many alumni who attended performances. One of her goals, she says, is for white, cis-gendered straight males to no longer be the default body on stage.

Taking time, post-production, to chat with Wesleyan, she explored the depth and breadth of alma mater’s influence on her art and endeavors.

Q: What brought you to Wesleyan?

A: I wanted to go a school with a really strong student theater program like my high school had—that was very obviously Wesleyan, with Second Stage. The organization not only supports new plays, but also classics, and I knew it offered great opportunities to grow as a producer and a director.

Q: Where did the German studies major develop?

A: I took this incredible Kafka class, a First Year Initiative course with Uli Plass, and fell in love with the department. I wanted to expand my knowledge of German language, theater and culture, so as a second-semester sophomore, I went abroad to Berlin. I declared the German Studies major while I was there.

Q: How did the two majors fit together?

A: All my professors encouraged crossover. Leslie Weinberg, my costume design professor said, “Oh, you’re a German major. How about you design a play that Brecht wrote?” I saw so much theater in Berlin that much of my aesthetic and understanding of how to create theater comes from there. Through those performances, which frequently combined theater with music, dance and film, I realized, I shouldn’t limit myself just to spoken text. I can include all forms of art and media in a theater piece.” When I came back to Wesleyan, I felt inspired to take classes across all forms of art—I took Ebony Singers, West African Dance, started a radio show with WESU FM and even started choreographing with Terp.

Q: What are your non-theater influences?

A: There was such diversity of thought in my classes—math majors in my German class, sociology majors in my theater class—and that contributed to the larger landscape of what I consider theater and performance.

I’m obsessed with the chef Grant Achatz. He questions the conventions of cooking, asking, “Why do you have to eat with a fork or a spoon? And why does it have to be served on a plate or in a bowl? Why can’t we come up with something new? Every element of the restaurant we try to break down and go, ‘Is this the best way it could exist, or is there a better version?’” I ask, “What, for the theater, are our tablecloths, forks, spoons, plates and bowls that maybe aren’t actually serving us anymore? Is how we are making theater and performance the best way it could exist, or is there a better version?”

Q: And how does this apply to your creation of In the Penal Colony?

A: The piece actually started out as my Directing II project.

Since it’s not originally a theatrical text, I use music, and dance, and sound to help tell the story. In Kafka’s story, there’s a machine that tortures the condemned over the course of several hours. I want to use the world of Harry Potter as an example. I love Harry Potter and read the books as they came out growing up. Before the movies, we each had our own idea of what that world looked like. It is more visceral for the audience to imagine their own torture machine than for me to recreate a physical one on stage.

So, we created that “machine” as a combination of the physical, visual and sonic codes the black male body has historically performed on TV, in our history books, and in the media. I choreographed a movement piece, and through that piece we teach the audience that this is the machine. We allow for the audience to autonomously interpret our string of code, developing a language, together, that represents and becomes the “machine.”

Q: And how do these ideas form to become what it is on stage?

A. I love research. I do a ton of research, which means everything from watching the latest episode of Insecure, to analyzing racist commercials from the early 20th century. I also put some of that work into the hands of my collaborators. I’ll ask the actors, “Can you do research on basketball moves? And can you do research on chain gangs? And then can you do research on apes?” I’m deeply interested in how my collaborators synthesize material. I want everybody to problem-solve and have ownership over the work; it makes us an ensemble.

Q: As a director, how do you handle all the pain that is palpable in the piece?

A: The most important thing is making sure that the emotional and physical needs of my team are met, understanding how outside influences affect the work we do and the weight we carry into the room. So, I plan for the first 30 minutes of rehearsal space is made for us to talk about what we saw on the news that day or how good that last episode of Atlanta was. The scariest part about In the Penal Colony is that even though we’re referencing a story that is almost a century old, the work remains relevant.

I also want to be clear that there’s deep intersectionality that seeps into the content of my work as well as my practice in the rehearsal room. Yes, specifically, in this play, we’re talking about the black male body. But that doesn’t mean we aren’t discussing the intersection of all identities. I want to make sure we’re respectful and reflective of all the identities in the room. Since I focus on work with and for marginalized communities who, in this climate, are constantly triggered, I prioritize we make space for each other, allowing for everyone to live in their full, unapologetic authentic bodies on and off the stage—before, during and after every performance.

Q: What do you love about directing?

A: Members of the cast, this group of brilliant black men—Jamar Brathwaite, David Glover and Dhari Noel—have said to me, “I’ve never been in a show with all black people. I’ve never been in a room where I can just be myself. I never thought a story that Kafka wrote would relate to my experience.” I am honored that as a director I get to create this space, do this work and tell these stories. It’s extremely important to me.

To see a video clip by Erica Snyder from the show, go to 7:05:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1ibDLAfgSV_YXExJjg8cy5KqY0pQZ3khr