The Troll Under the Bridge

The Fremont Troll is 28 years old, 18 feet tall, and lurks beneath the Aurora Bridge in Seattle. It was Steve Badanes ’65 who put it there. Now the Howard S. Wright Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington, Badanes had designed the troll with a few of his students as part of an art competition aimed at rehabilitating an area that had fallen into disuse. While his 40-plus-year career has included many award-winning projects, it is the concrete and rebar colossus clutching an abandoned Volkswagen Beetle that Badanes says is his best-known project and the one that has made the most people happy. “Trolls’ worst enemies are development and pollution,” Badanes said during a visit to Wesleyan to discuss his work this fall. “They’re very peaceful unless aroused, and that’s the statement we’re supposedly making with this piece.” Today, Badanes directs the Howard S. Wright Neighborhood Design/Build Studio, where students tackle community projects for Seattle-area nonprofit groups. Wesleyan named him a distinguished alumnus in 1990.

(Photo courtesy of Steve Badanes ’65)

Online extra: 2018 Silipo ’85 Lecture: Badanes ’65 on Design-Build Architecture

This October, Associate Professor of Art Elijah Huge invited Steve Badanes ’65 to speak at the Samuel Silipo ’85 Lecture. Introducing Badanes, Huge noted that he and his architectural design students were already in preparation for “our seventh small-scale design-build project this upcoming spring, something that was very much inspired by Steve’s work.”

Badanes is the Howard S. Wright Professor of Architecture, director of the Neighborhood Design Build Studio at the University of Washington, and a partner in Jersey Devil Design Build, an architectural firm perpetuating the tradition of medieval craftsmen.

“I first met Steve at a party in Berkeley,” said Huge, “and had long admired his work, which I first discovered—or at least, with the hubris of a young graduate student, imagined I had discovered—in a strange book called Devil’s Workshop: 25 Years of Jersey Devil Architecture that had all these weird buildings in it that looked like animals or snails or sandwiches or footballs. The work seemed to come from an entirely different planet and was not just designed by architects, but built by architects, on site. It was an alternative form of practice focused on craft, not only as a matter of how things were put together, but also as an opportunity to be playful and imaginative. It seemed only fitting to invite Steve Badanes back to Wesleyan to talk about his work, which includes some of the formative years of the design-build movement.”

To see photographs of the buildings that Associate Professor Huge references—as well as several more images of the Fremont Troll (including a couple of the builders and the construction process)—please see Jersey Devil Design Build.

Below are highlights from his talk:

“I went to both Wesleyan and architecture school in the ’60s,” began Badanes, “and in the ’60s, 50 years ago, the architectural profession was even more conservative than it is now.” He and his friends, however, found a way around that. “We joined together with a couple of classmates to start a company called Jersey Devil. It was a group of architects, artists, and inventors committed to the interdependence of design and construction.”

Their “office” was actually a post office box in rural New Jersey. “We were pretty itinerant, working out of wherever our commissions took us. We did all the construction ourselves, typically living on-site, either in trailers or in group-built structures.”

With a slideshow to illustrate his favorite creations, Badanes provided commentary on the architecture and the work that spans his career.

Back in the ’60s, he recalls, his cohort thought that constructions of the future would be inflatable: “Lightweight, air-supported buildings, easy on the pocketbook, easy on the landscape, incredibly high in fantasy content, either the thinnest of skins between you and the outside, or kind of hermetically sealed in these alien envelopes,” he recalls.

“It was a fabulous fantasy but a fantasy based on cheap energy: enormous amounts of air would be blown in to keep these things from falling down, and of course enormous amounts of energy to heat them and cool them. So what we tried to do when we graduated from school was to retain the spirit of these buildings in a more energy-efficient package.

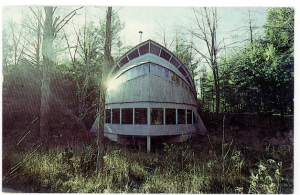

The Jersey Devils built their first home in 1972 for a steamfitter and his family. “We never did an apprenticeship,” he told the Wesleyan audience. “I think if we’d ever worked in an office, we wouldn’t have thought it was such a fabulous idea to build a column by stacking these 2,000-pound manhole sections, framing it with curved barn rafters, sheathing it with cedar, and then spraying it with urethane foam. When you first get out of school, you want to use every single idea you ever had in the first project you get. The results are not always timeless.”

Following that structure, but in New Hampshire, the Jersey Devils built what has been dubbed the “Helmet House” for the remarkable likeness the façade bears to a warrior’s protective gear.

“This is the first building we got some national, and actually international, publicity for. Japanese magazines picked it up because of the Samurai look. The National Enquirer gave it the Weird Home Award in 1978.”

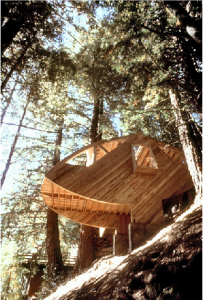

After his move to the West Coast, they created the Football House, so called for its rounded shape that extends into a point out beyond the side of the hill into which it is built, high above the valley below. “They tell you in architectural school that if you can draw it, you can build it. But they don’t explain about how you have to get way out in the air like that to build this structure.”

Even as he narrates with cheerful, wry humor poking fun at his earlier self, he has purpose. “I like to start with these old buildings that Elijah referenced in his introduction, so you can observe how far we had to go, how little experience we had, and how much courage we had to go out in the woods and try and build these things.

“And you can see how much fun the ’60s were, and how much those ’60s values are responsible for where we ended up.” And “weird house” award or not, the Jersey Devils build with some practical lessons in mind.

“Our work illustrates some ideas:

- The idea that the structure can generate the form.

- The idea that a building can collect and store solar energy.

- The idea of simple geometry and local materials that form the basis for all the work we’ve done since then.”

The ecology movement was an important influence in the 1960s also, and the homes that Jersey Devil began creating and building when they moved to California incorporated this consciousness. Badanes and his team also adopted some of these technologies in their daily life at the design/build site. A solar oven made from a window, mirrors, and an insulated box cooked their food (“even burnt a roast,” he adds); they used solar energy to make sea water potable and a windmill to pump water at some sites.

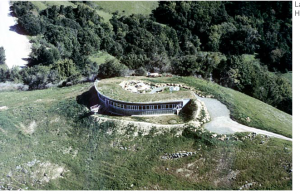

Badanes describes Hill House as “the first Jersey Devil project that put together all the environmental discoveries that were emerging in the ’60s.” The site, he says, is about 50 miles south of San Francisco, 2,000 miles from the Pacific Ocean, and a couple thousand feet above sea level. The result: “There’s nothing between it and these huge storms that come off the ocean. We had 125-mile-an-hour winds during the construction of this building.”

The design was a product of the site: “We scooped out the top of the hill, set the house in there, where the wind would go over it but the sun would come in where we could use it for heating and for day lighting. Then, by following the contours of the hill, we pushed the wind around it, creating a wind-free courtyard on the north side of the building. And by bringing the earth and grass up on the top, we give it some ballast and integrate it with the amazing site. It’s a pretty simple plan.” The resulting home, built by architects who were living on-site and understood how to intimately integrate the house into its environment has, literally, stood the test of time, remaining a safe haven on that windswept hill for decades.

“We did 25 years on the road, living on sites, building houses, working in a lot of different climates,” recalls Badanes, enumerating a few: a passive solar house for an airline pilot on the high planes of Colorado, “hunkered in to protect it from tornadoes,” and offering “a strong, dark silhouette against the white winter landscape.” Another one, in the Everglades, offered a writer a studio in which to work and watch the sunset, while providing an outdoor—but covered—site where her partner, a woodworker, could pursue his art. “It’s also cooled without air conditioning in one of the hottest, most humid parts of the country,” Badanes notes. “Screened porches on the east and west serve as thermal buffers. Foil radiant barriers in the roofs and walls make it just like a space suit, and with air constantly moving through, it cools itself.”

When he was nearing 50, he says, he was ready to leave the itinerant lifestyle he’d enjoyed. He accepted a position with the University of Washington during the year, and in the summers he joined with other Devils for Yestermorrow Design Build School in Vermont. “Spending time with young people who are still optimistic enough to believe that their ideas can change the world and make it a better place has definitely kept me from becoming too cynical,” he said and encouraged the students listening to attend the Yestermorrow School, where his class designs and builds a project for the local Vermont community during the first two weeks in August.

His work during the University of Washington’s academic year, as the Howard S. Wright Professor of Architecture, director of the Neighborhood Design Build Studio, also supports the community. Projects there included a project at the Danny Woo International District Community Garden in Seattle. Most of the gardeners are Asian refugees and over the age of 62. Communicating with these gardeners, Badanes and the students developed a master plan. “Over the years, we’ve built a number of simple structures, which are in an architectural style that’s familiar to most of the gardeners, including a tool shed, a vegetable washing and drying area, and raised beds for the elderly, so they don’t have to bend down so much to garden.” Additionally, the class built a pit for the Pig Roast—which has been a community event for 35 years, yet the gardeners had never had a dedicated space in which to gather for this highlight.

The lessons he’s teaching are not all about architectural structures, he notes. “If you do community work for the people who really need your help, life will turn out fine. That’s the message I’m trying to impart,” he says. “Everybody wins in this scenario. The students get to work for some real clients and learn something about building. The clients, the gardeners in this case, get the fruit of all that labor.

“What we’re trying to say is that hand craftsmanship and the ethnic traditions in growing food are an important use of land in the city—which is a lot of things for a tiny project by a handful of architecture students to say.”

While this may be the core of his practice, Badanes notes that one of his projects “definitely stands out; it’s definitely made the most people happy.” Of course, it’s the Fremont Troll, “the only piece of public art that was the result of a public vote competition,” he recalls.

In 1970, Fremont Arts Council received a Neighborhood Matching Funds Grant for $20,000 to create something to go under the bridge. “I entered with two of my students, I was just starting at UW and we proposed—obviously to go under a bridge—a troll. We didn’t know much about what a troll looked like, so we went to the library and looked wherever. Wherever we weren’t sure, we just figured we’d go with a little more hair.”

A car, they decided, would be an element that would give it some scale. “Some people said it should have a California license plate,” he notes, which they added.

The jury of local artists and artisans selected three other ones for the public to vote on and those were awarded $500; Badanes and his students received nothing, but were allowed the opportunity to enter the contest nevertheless. In a six-to-one landslide, the public chose the team’s troll as the sculpture they wanted beneath their bridge.

“Everybody came out to help us build it, but it was a challenge. We made the model out of drywall compound. We sliced it with a band saw and developed cross sections. We bent up number-three rebar, put in a lot of mesh, and we figured that the only real detail work was the fingers and the nose. That nose looks quite a bit like mine. We needed one to use as a model—and out of the whole crew, mine got chosen. The Volkswagen was donated without a motor; it had been in a rear-end crash. Kids came from all over Seattle to put stuff in there for a time capsule. We had only been given $20,000 to build it, but after we paid the insurance and everything else, it was more like $15,000. So we raised a little extra money on-site by selling Fremont Troll t-shirts and shower caps, the ultimate fashion statement in a city like Seattle, where there’s always a chance of showers.

“Troll Plaza was basically done. The retaining wall is made out of ‘urbanite,’ which is broken-up city streets, which of course they give those to anybody. There are these leaking expansion joints over his head, so all winter long, gruel and moss come sliming down over him, which I think works—for this sculpture anyway. The eye is a VW hubcap covered in a prismatic defraction grid, so when a car comes up over the hill and headlights hit this eye, the driver sees a blast of light.

“At the dedication ceremony, he was totally covered in kids, which he is all day long every day now. He celebrates all the holidays, especially Halloween, which is called Trolloween in that neighborhood. People get married here too.

“It’s really transcended public art, and it made the political statement that Seattle—and the Fremont neighborhood, in particular—needed to make about 1990, and it helped start a community tradition in Trolloween, which will hopefully be around long after I’m gone.”