FROM THE VAULT

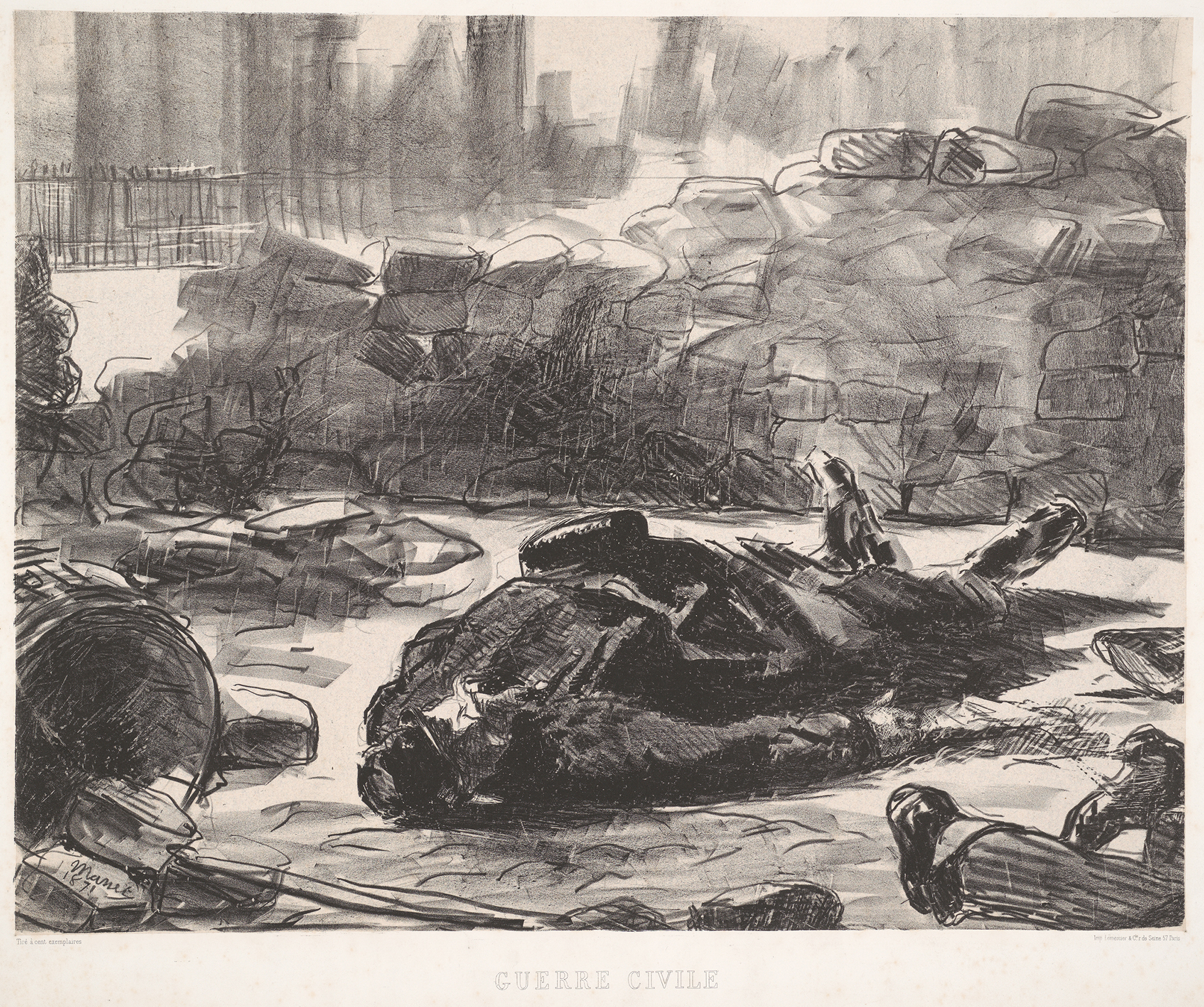

One of the most moving protests against civil war is the lithograph, Guerre Civile (Civil War) drawn by Impressionist artist Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883), and published in 1874. Signed and dated within the image, “Manet 1871,” the dramatic print bears witness to the massacre of the Parisian Communards in 1871 by French government forces. In creating this image, Manet echoed some of the most famous, and most revolutionary works of art by his predecessors, and produced a work that is evocative and calm, immediate and incendiary.

Civil War represents the end of the tumultuous events of the Franco-German War and the Siege of Paris, in 1870-–1871. Manet sent his wife and family to the Pyrenees, but stayed in Paris, where he and many of his fellow artists joined the National Guard to defend the city. The German siege of Paris lasted from September 19, 1870, to January 28, 1871, when the French republic agreed to an armistice. Following the armistice, the newly elected French National Assembly met in Versailles, while the predominantly working-class National Guard continued to hold Paris. After the municipal elections on March 26, a group of socialists and revolutionaries declared a rival government known as the Paris Commune.

On May 21, the Versailles government troops entered Paris and ruthlessly destroyed the Communard defences at barricades throughout the city, in what became known as the “bloody week.” More than 20,000 Communards were killed, and a further 38,000 arrested.

After enduring the German siege of Paris, Manet left in February 1871 and returned in late May or early June, either during the “bloody week,” or very shortly thereafter, while the government repression still continued. His biographer, Théodore Duret, reported that Manet based the lithograph, Civil War, on a sketch he made from life at the intersection of Rue de l’Arcade, and the Boulevard Malesherbes. At the top left of the lithograph, Manet drew the iron railings of the Church of the Madeleine, and indicated the distinctive colonnade of the church façade with broad vertical strokes.

In Civil War, Manet confronts the viewer with the corpse of an unidentified Communard dressed in the uniform of the National Guard, killed at one of the barricades. In the right corner lie the legs of another corpse, a civilian dressed in striped pants, perhaps a passerby unlucky enough to be caught in the recent crossfire. The dramatic foreshortening brings the viewer into the scene and quotes the composition of Manet’s earlier painting, The Dead Toreador, ca. 1863–1864. It also recalls the foreshortened corpse in Honoré Daumier’s most famous political print, Rue Transnonain, 1834, as well as the bodies strewn at the feet of the figure of Liberty in Eugene Delacroix’s oil painting, Liberty Leading the People, 1830.

The sense of witnessing the event is emphasized by Manet’s choice of the printmaking technique of lithography. One can imagine him standing in front of the lithographic stone, as he held the crayon sideways to create broad flat strokes, then wielded the sharpened end of the crayon for emphatic, rough details. After building up the crayon marks, Manet then scratched highlights in rough lines. The dramatic cropping of the image at right and left suggests that the scene continues beyond the borders of this sheet. The background is constructed of loose blocks, evoking both the atmosphere of Impressionist paintings, as well as the smoke of the many buildings that burned during the “bloody week.”

Although Manet wrote the date of “1871” on one of the cobblestones in the foreground, he probably created it in 1872-73. The print was not published until 1874, when it was printed in an edition of 100 by Lemercier & Cie. In comparison, Manet’s other depiction of the massacre of the Communards, The Barricade, 1871, was considered too incendiary and not published until after his death in 1884.

Recent scholars have argued that Manet was a radical in terms of aesthetics, but a moderate in his politics, a republican who criticized the monarchy and the Commune. Nevertheless, he was appalled by the indiscriminate violence of the government forces. Berthe Morisot’s mother wrote her a letter on June 5, 1871, referring to Manet and Edgar Degas as “Communards” because they condemned the violence of the Versailles army. The stillness of the scene of Civil War appears at first glance to be a neutral condemnation of both sides. Yet, the dead man holds a white cloth or handkerchief in his hand, suggesting that he had waved a white flag of surrender, before he was shot. —Clare Rogan, Curator, Davison Art Center