A CENTURY UNDER CONNECTICUT SKIES

For two years, beginning in the summer of 1914, a rather strange looking structure took shape atop the crest of Foss Hill, highest point on the Wesleyan campus. Silhouetted against sunset skies that smoldered over the rolling farmland west of the university’s campus, it was a squat brownstone building whose large, dome-capped “silo,” appended to its eastern face, might have suggested a barn.

It was, in fact, the university’s first dedicated astronomical observatory. Designed by the renowned architect Henry Bacon—best known today for the Lincoln Memorial – it was a key feature of the master plan that Bacon proposed for development of the Wesleyan campus.

The building was named for Professor John Monroe Van Vleck, who taught mathematics and astronomy at Wesleyan from 1853 until his death in 1912. Funding for its construction began with a $25,000 donation from Van Vleck’s brother, Joseph.

Overseeing construction of the new building was a tall, lean, immaculately attired man whose long, serious face was accented by a pair of decidedly professorial wire-rim glasses. He was Frederick Slocum and he had just been named Wesleyan’s first full-time professor hired solely to teach astronomy. He brought considerable experience to the post.

An 1895 graduate of Brown, Slocum earned his PhD in 1898. For a decade he remained at Brown, first as an instructor in math, then as assistant professor of astronomy. Then, in 1908, he turned away from teaching and focused on research. After a year at the Royal Astrophysical Observatory in Potsdam, Germany, the world’s first observatory to emphasize astrophysics research, he joined the Yerkes Observatory at the University of Chicago as an assistant. There he dedicated the next five years of his career to the study of solar prominences, immense bulges of gas that loop out from the surface of the sun, and the use of photography to measure stellar distances.

Slocum was just 41 when he arrived in Middletown in 1914. He became director of the observatory in the fall of 1915, and from then until 1923, when the first additional faculty member was hired, he was the department. He would oversee the department until 1944, when failing health forced his retirement.

The Van Vleck Observatory was completed in 1915 and opened for classes that autumn. It was formally dedicated in June 1916.

The principal tool used for astronomical exploration at that time was a remarkably beautiful telescope called the Van Vleck Refractor. More than 27 feet long, it would ultimately be equipped with a powerful 20-inch refracting lens, although delivery from Germany of the glass for the lens was held up several years because of World War I. The iconic dome of the observatory was built to house this device and it does so to this day. It served generations of Wesleyan astronomy students and professional astronomers, alike, until it ceased to have utility for astronomical research in the early 1990s.

The old telescope remained popular with visitors, however. About 1,000 people have visited the campus every year to peer through its eyepiece and marvel at objects as near as the moon and as far away as millions of light years. It is one of Wesleyan’s great points of distinction.

“Refracting telescopes give you the most beautiful views, because they have the cleanest optics,” says Bill Herbst, John Monroe Van Vleck Professor of Astronomy and former director of the observatory. “They are very good for looking at planetary surfaces.”

A century of use caught up with the telescope, and in 2014—with the observatory’s centennial just over the horizon—the department decided to give the device a much-needed renovation. A number of modifications made to provide the device with electronic controls in the 1960s had deteriorated, and the entire telescope badly needed cleaning. So, over a span of 15 months, it was completely dismantled, cleaned, and reassembled, returning it to near original condition, with the exception that it is now computer-controlled. This will increase its utility for both students and the public, making it possible for the telescope to be used on many more nights each year.

When the Astronomy Department began planning the telescope’s restoration, Research Associate Professor of Astronomy Roy Kilgard reached out to Associate Professor of History Paul Erickson and inquired if Erickson and others in the History Department would be interested in exploring the observatory’s history in connection with the centennial. Erickson, who has taught history of science classes in which students have visited the observatory, leapt at the opportunity.

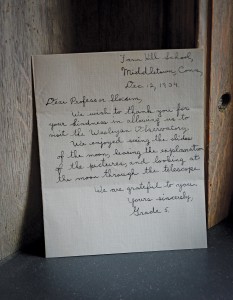

At that point there were no formal plans for the centennial celebration, but “as we looked into it and discovered exciting artifacts, we became more excited and the project grew,” Erickson recalls.

For starters, the physical layout of the century-old building was of historic interest, reflecting a very different era of astronomy. “The observatory makes sense only in a context where moving data around is very, very difficult,” Erickson explains. In a time before astronomical calculations were made using compact computers, “data weighed something. It was massive and very difficult to move from place to place.”

The building had two rooms for computational work in support of astronomical research, some of which was carried out by female staff; and its layout aimed to accommodate the work of astronomy as what Erickson calls a “place-bound enterprise.” Astronomy today is about observation done remotely, using telescopes on mountaintops and in space, and radio telescopes. Astronomers all over the world request time on these far away devices and monitor results with their computers.

Consequently, the Van Vleck Observatory, no longer the research facility for which it was built, is something of a time capsule. But what a time capsule it turned out to be. Erickson and Visiting Assistant Professor of History Amrys Williams soon found that its dark corners, closets, and crannies were packed with a treasure trove of antique instruments and records chronicling the observatory’s history and, by extension, the history of 20th century astronomy.

Supported by a team of six students, Williams, Erickson, and Kilgard began to inventory those dusty assets last summer. It was no simple task. A collection of thousands of glass-plate photo negatives of astronomical observations—both extremely heavy and fragile—confirms Erickson’s point about the weight of old astronomical data. Each slide is preserved in a sleeve marked with astronomers’ notations. Many are in Slocum’s elegant cursive script.

The summer research turned up additional pieces of a nearly 200-year-old mechanical model of the solar system known as “Russell’s Stupendous and Magnificent Planetarium or Columbian Orrery,” long thought to have been lost, which was exhibited to the public by the university in the 19th century. And it shed new light on a fully operational turn-of-the-century mechanical calculator called the “Millionaire,” purchased by the university in 1915, and used to quickly make the parallax calculations required to measure stellar distances; and a guestbook in which the signatures of visitors to the observatory, including many prominent scientists, were recorded from 1916 until 1944.

In the fall, with much of the initial inventory complete, Williams taught a course called Public History, which afforded her an opportunity to use the centennial as a unique teaching opportunity. “My students surveyed visitors, conducted oral histories with alumni, faculty, and amateur astronomers, honed the key narratives we wanted to communicate, selected objects and artifacts to tell those stories, and drafted detailed plans for the exhibition and associated public programs,” she explains. “Seldom can professors offer their students such an opportunity to do hands-on work in historical research and public interpretation.

As a result of their work, the value of the observatory for teaching and research on the history of science will be greatly enhanced.”

“Working on the observatory project was a great learning opportunity,” says Michaela Fisher ’17, a history major from San Diego, one of the six interns who assisted with initial research last summer. “We really started pretty much from scratch, finding objects throughout the observatory, creating an inventory, and using the university’s archives to understand the significance of the objects. It was a wonderful, hands-on experience.”

The exhibition will open to the public on May 6. A symposium and rededication of the observatory will occur on the 100th anniversary of its dedication, June 16. For more information about the observatory and centennial plans, visit the project’s website: underctskies.wesleyan.edu.

Learning in the Dark

Max Lee ’16, one of the six students who assisted Paul Erickson and Amrys Williams with the inventory of historic artifacts at the Van Vleck Observatory during the summer of 2015, has spent most of the 2015–16 school year studying and interpreting the observatory’s 100-year-old guestbook. Following is a short passage from a draft of Lee’s extensive manuscript about the guestbook, describing a solar eclipse that drew visitors from all over the world to Wesleyan.

On January 24, 1925, astronomers from around the world met at the Van Vleck Observatory in Middletown, Connecticut. The occasion: a total solar eclipse passing directly over the Observatory.

A group from the University of Virginia attached a tent to the side of the Observatory. Two European astronomers—Charles Lassovsky of the Hungarian National Observatory in Budapest, Hungary, and George Lassovsky of the University of Louvain in Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium—sailed to the United States. A group of astronomers traveled from the Mount Wilson Observatory in Mount Wilson, California.

The location of the eclipse offered astronomers a chance to observe a solar eclipse with large, unmovable equipment. Normally, astronomers’ resources were much more limited. On an ordinary eclipse expedition, such as one that Wesleyan professors Frederick Slocum and B. W. Sitterly went on in 1932 in New Hampshire, astronomers would bring makeshift tents and smaller telescopes that could easily be transported across large distances. The practice comes out of necessity. A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon casts a shadow over the Earth. Because the Moon is small relative to the size of the Earth, this shadow covers only a small fraction of the Earth’s surface—typically, in rural regions of the world. Without any permanent telescopes, astronomers brought their own.

Especially in the early 20th century, solar eclipses offered valuable scientific opportunities for astronomers. Just 10 years before the 1925 eclipse, Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity, which holds that gravity bends light. Solar eclipses offered a way for astronomers to test the theory. Because the sky was dark, astronomers could see stars whose light traveled in the direction of the sun and, according to Einstein’s theory, should have been shaped by the Sun’s gravity. In a solar eclipse expedition in 1919, Sir Arthur Eddington confirmed Einstein’s results. In 1913, Niels Bohr proposed a new model for the atom, which stated that elements are absorbed at specific wavelengths. Astronomers were able to use that finding to determine the elements inside stars. But, according to Slocum, the only way to find the elements inside our Sun was to observe it during a solar eclipse.

During the 1925 eclipse, astronomers set out to verify scientific theories and learn more about solar eclipses. In the tent erected against one wall of the Observatory by the University of Virginia team, astronomers took flash spectra of the solar eclipse, the technique for finding gases in the Sun. According to the New York Times, some scientists, likely the University of Virginia astronomers, discovered a new gas in the Sun using observations from the solar eclipse. Elsewhere, physicists tried to learn how eclipses affect radio waves.

After 1925, astronomers continued to observe during eclipses. But, once again, they returned to conducting observations using makeshift, mobile observatories, and the groups were much smaller than the one that appeared at Wesleyan University in 1925. Frederick Slocum and B. W. Sitterly both took part in those observations, joining small teams. In 1927 they observed in Norway; in 1932 they went to New Hampshire, only to have their observations obscured because of clouds. There were just six people in the New Hampshire eclipse group, compared to over 20 who observed at Van Vleck Observatory seven years earlier.