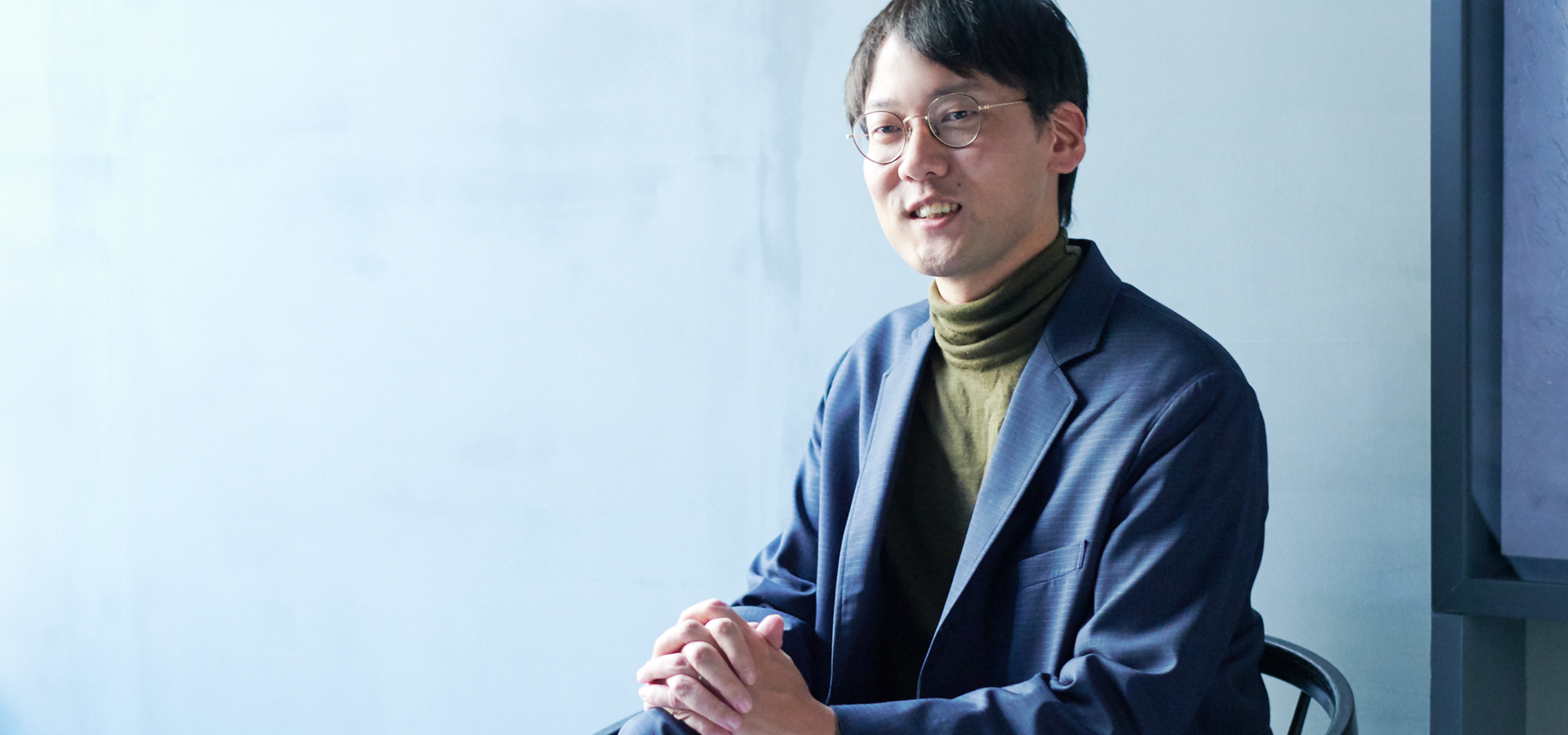

SYLVIA RYERSON ’09: RADIO FOR THE INCARCERATED

Restorative Radio offers longform audio pieces that broadcast the sounds and voices of home to those behind prison walls.

“By design, prisons are the most censored institutions in the country. Letters are screened, phone calls possibly tapped, visitation time is restricted, but radio can penetrate prison walls,” says Sylvia Ryerson ’09, who spoke at this year’s Shasha Seminar. The founder of Restorative Radio, she produces “audio postcards” to send the sounds of home to those in prison.

A double major at Wesleyan—music and American studies—she traces her work to a seminar taught by Professor Demetrius Eudell on the prison system, followed by a summer internship at a rural Kentucky radio station, WMMT-FM. A.liated with Appalshop, Inc., a not-for-profit arts center, its mission is: “to be a 24-hour voice of mountain people’s music, culture, and social issues … and to be an active participant in discussion of public policy that will benefit coalfield communities … .”

The summer of her internship, the community was discussing the impending construction of yet another prison in the region. There were already seven new prisons within 100 miles of WMMT.

Most of the country’s recent prison expansion has occurred in economically depressed rural areas—regions without public transportation and far from the cities that are home to the majority of prisoners, stressing crucial family bonds, Ryerson notes.

Returning to WMMT after graduation, Ryerson became a host of Calls From Home, a weekly radio show that o.ers a toll free number for prisoners’ families to record messages for broadcast.

For four years, Ryerson and her co-hosts listened as lives unfolded—reports of weddings, new jobs, babies born. “It was heartbreaking—and it was uplifting: We were witnessing amazing perseverance. People were staying connected; grandmothers called in to sing songs or read poems.”

Ryerson wanted one more thing from the show: “How could we touch a larger audience with the message that incarceration affects a whole family, a whole community?”

She began to plan longform pieces that would capture the voices of home in an immersive soundscape that would reach those in prison and appeal to a general audience. With some grant money behind her, Ryerson traveled the state of Virginia, connecting with people she’d known only by name and voice from the radio show.

In the nine postcards produced so far, she’s recorded families hosting Sunday dinners, parents and siblings sharing favorite memories, and nieces and nephews offering greetings to an uncle they’ve never met. She’s recorded a grandmother attending church, and she’s helped a fiancée capture the sounds of daily life—a walk around her neighborhood, cooking pancakes for breakfast.

While Ryerson says that the ultimate measure of the project’s success is what it means to families, her goal is to stimulate discussion and be a catalyst for change.

“In our society, people in prison are reduced to a number, stripped of humanity. So it is powerful to broadcast these voices to show that those incarcerated have entire communities that love and miss them and are waiting for them to come home. My hope is for these postcards to remind the world, and even prisoners themselves: There is a place where they belong—and it’s not in prison.”