From Glass Ceilings to Glowing Screens

Jane Eisner ’77, P’06,’12 and daughter Miriam Berger ’12 discuss the profession that is their shared passion.

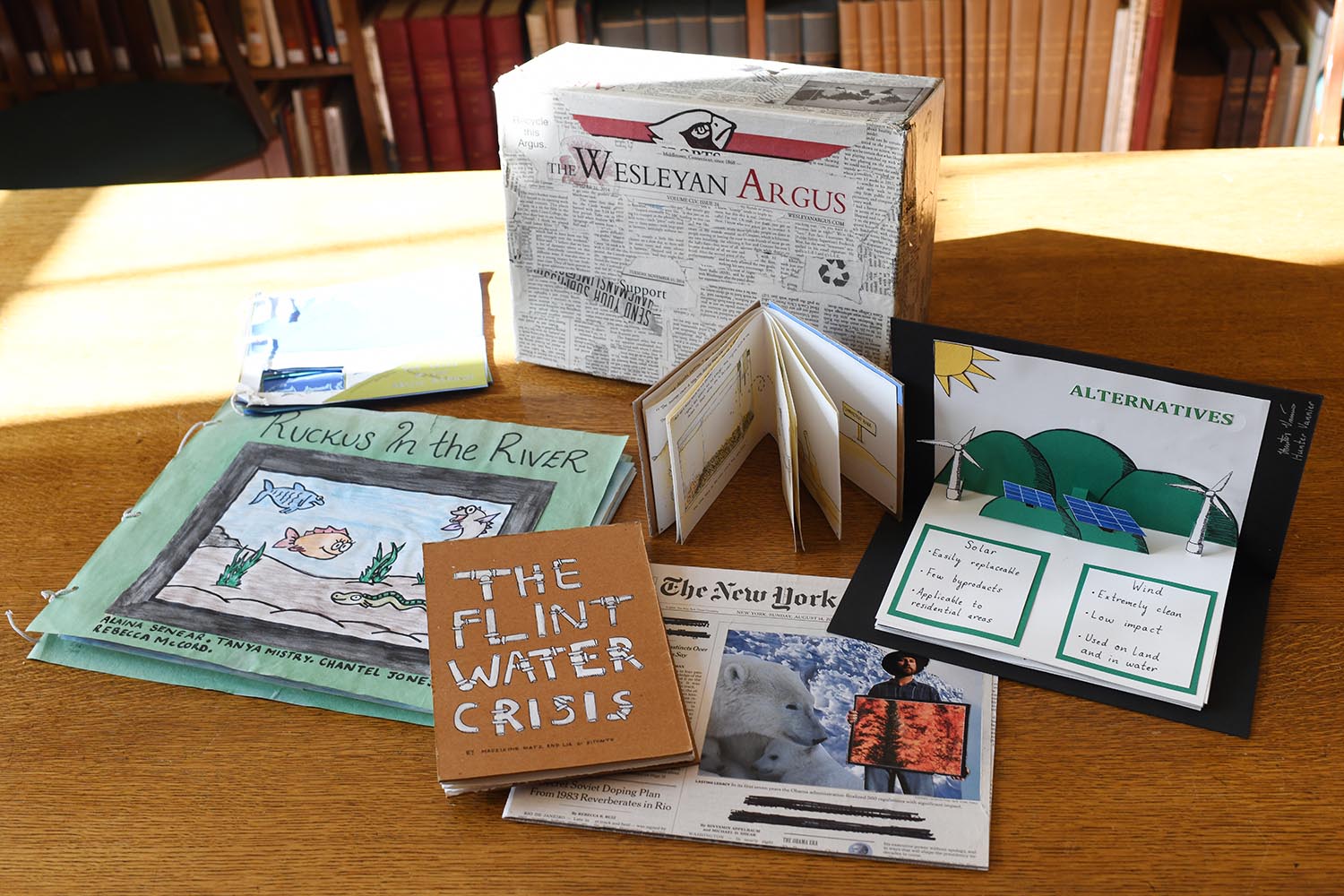

Jane Eisner ’77 is editor-in-chief of The Forward, the national Jewish news organization. Together with Mark Berger ’76, she is the proud parent of Miriam ’12 and her two older sisters, Rachel ’06 and Amalia (Tufts ’10). Miriam Berger is a freelance journalist currently based in Jerusalem and reporting on people and politics in the Middle East. She majored in the College of Social Studies at Wesleyan and (surprise) wrote for The Argus. We asked Jane and Miriam to reflect on their careers in journalism.

Q: Jane, why did you decide to become a journalist?

Jane: This will sound corny, but it’s true: I’ve been enchanted with journalism ever since I was in the seventh grade and watched old reruns of Edward R. Murrow, the legendary CBS radio and television broadcaster. I was in awe of the way he assembled facts to tell a compelling story, and to challenge authority, and to bring into American homes the sounds and horrors of war. When I later taught journalism at Wesleyan, I subjected my students to watching hours of Murrow! The style of storytelling has changed since then, of course, but the elements remain.

Plus, I was nosy. And I liked to write. And, as the first woman in my immediate family to go to college, I saw journalism as a meritocracy I could conquer.

Q: You must have faced challenges, right?

Jane: Early on, I confronted the limitations of being a woman in a profession that still was dominated by men. I only worked for a year on my high school newspaper because the advisor was a horrible misogynist, and I saw no other recourse but to quit.

Even at Wesleyan, where there was more opportunity for me as a woman, I often felt like an anomaly. I was the first woman to become editor of The Argus—and the only woman on the editorial staff. Since then, I have been the first woman, and certainly the first mother, in so many positions that I’ve honestly lost count. I feel blessed to have entered journalism at the moment doors began to open for me—largely because of the fearless work of my older sisters, who had to bang on those doors hard and loud to create a path for the rest of us.

What propelled me from the start was the need to tell the stories of the people around me, especially those who did not have access to power. I subscribed to the notion that journalism ’afflicts the comfortable and comforts the afflicted.’ My first job out of graduate school was in southern Virginia, where I covered education only two decades after “Massive Resistance,” when white schools in the state shut down for a year rather than integrate. I witnessed injustice up close and it was my job to write about it.

Q: Miriam, why did you decide to become a journalist?

Miriam: I honestly don’t know if I would still be in journalism if it wasn’t for my mother’s support. In the last six years I’ve reported from around the Middle East (and parts of Africa and Central Asia) often as a freelancer, or a one-woman-show: finding, fixing, and translating my own interviews, pitching the stories to editors and hustling to get them out. It’s an exhilarating privilege. And it’s also emotionally exhausting. That’s why I’m so grateful to have my mother as a mentor who I can complain to (you’re doing the right thing is often just the encouragement I need to hear) and seek out advice. And seeing her fulfilling path as a female journalist, though quite different from my own, helps to give me the confidence to strive for more.

Q: How do you compare your path to your mother’s?

Miriam: There are so many glass ceilings my mother’s generation of journalists (and women in general) faced and smashed and faced again so that I wouldn’t have to. Sometimes, though, I am nostalgic for the journalism model that I grew up with: where you worked your way up in a paper, which the family poured over each morning at breakfast. Now I often have to remind my family that I’m actually working while pouring over my phone at the table. In college, when I first started seriously considering a news career, I never expected that I would be a freelance journalist, or freelance anything for that matter. But what’s kept me going is the space it gives me to find ways to keep those same shared values at the core of what I do.

I decided to work as a journalist because it’s who I felt I was and because I could. I wanted to write about what people and institutions with power do and how that impacts and shapes the world around us. And about the individual lived experiences and the big global trends that define the choices at hand, and the shared human experiences and connections and empathy—and better policies—we can forge by really engaging with one another. I’ve been able to make my own way in part because of the independence and support my family’s given me. And what makes me most nervous is not simply earning enough money each month, but that to make it in much of journalism these days it’s expected that you have all these resources and more from the start, thereby often excluding different classes and communities from the profession at everyone’s expense.

Q: Jane, what have you written about that speaks to your goals and has been energizing?

Jane: Writing about people without power: I am proud of an essay I wrote earlier this year about Palestinian nonviolent resistance. In the context of running a news organization that serves the American Jewish community, this deep dive into a controversial subject was both difficult and exhilarating. I was mindful that I was writing for an audience that would be skeptical, at best, and I needed to tell this story in a way that acknowledged my readers’ sensitivities and fears so that they would see this for what it was—journalism, not propaganda. At the same time, I really had to get it right.

I reported the story while on an organized trip that was officially off the record. The agreement was that I would get permission afterwards to quote anyone by name. So, there was a lot of back and forth on email and phone to ensure that I was not violating anyone’s trust, given that some Palestinian sources were taking risks to talk to us and some American Jews were taking risks talking to these Palestinians in the first place. All the trouble was worth it, in the end, and I am grateful that I work for an organization that values this kind of journalism.

I am also proud of the work we’ve done at The Forward to highlight gender inequity in the Jewish world. When I took this job ten years ago, I was stunned by how few women were in leadership roles in Jewish nonprofits. So we created an annual survey, listing who is in charge and how much they earn, in the top 70 or so national nonprofits. Although this is all public information, it is difficult to find and analyze, and no one had done this before, so it created quite a stir. While huge gaps remain in leadership and salaries, we have been able to highlight the inequities—and now, in this #MeToo moment, people are finally starting to pay attention.

Q: Miriam, same question to you.

Miriam: One of my favorite stories I’ve written this year was for Wired about the politics behind the limited driving apps for the Palestinian Territories and the larger significance of mapping these parts. If you want to make the short drive from Jerusalem to Jericho, for example, Google maps will tell you that it can’t find a way. Other apps will tell you that you are entering a high-risk area or that access is prohibited by Israeli law. The story idea came about from me just driving all around Israel and Palestine … and asking questions to myself as I switched between different apps trying not to get lost or be too late. I think it’s important to document what big companies and institutions say they do and the daily reality people experience on the ground. I also love to write about “niche” topics like transportation (or food and labor) because it’s something that readers can really relate to even if they’ve never been to the place. (The newish New Yorker in me can talk about subways forever.)

Another favorite I wrote was about a special kind of kunafa (a Middle Eastern sweet) found only in besieged Gaza, and the politics behind the dessert’s isolation, for the BBC. What happily surprised me was the positive responses I received from readers in Gaza and elsewhere who were interested to see the war-ridden strip represented through a different lens.

Q: Jane, what do journalists need to know that’s different than when you were getting into the profession?

Jane: Almost everything!

The digital space has transformed journalism. A reporter today must be faster, smarter, more attuned to audience, skillful across multiple platforms, and more willing to engage readers than I ever had to be when I was starting out. It’s a much more demanding and ruthless profession, and I feel badly sometimes that Miriam has chosen to do this at such a moment.

That said, it is also far more open than ever before. Even though I recognize that young women still face obstacles that male colleagues don’t, there is much more opportunity to be as ambitious and creative as you want to be. In my early years, women like myself were afraid of ambition, and didn’t know what to do with our grand aspirations. How do we succeed in what was still a man’s world? How do we manage work and family life? What would it look like and sound like if we really were the boss? Those questions haven’t been fully answered, true, but we are in a different place now.

And, in the end, even with the digital transformation and lingering gender disparities and all the other challenges, it’s still about the journalism. Uncovering uncomfortable truths. Telling great stories. Having an impact. The verities remain. Which is why I know that it’s the right profession for Miriam!

Q: Miriam, what would you say to someone thinking about a career in journalism?

Miriam: I’d say do it! Work hard (and ethically) and hustle. And also do it in your own way: My career path hasn’t been linear—I detoured for a master’s degree in modern Middle Eastern studies and have spent a lot of time studying languages along the way.

But to editors, I’d also say: the current model from my vantage point is unsustainable. You need to pay freelancers more. Period. You need to cover more reporting expenses (especially in repressive places). You really need to respond to pitches and emails (it’s kind of the bane of our existence). The media needs to always be working towards including a greater diversity of voices and sources, including among its own reporters and editors. So, I’d say less free snacks in offices on the coasts and more money for livable salaries and reporting from the ground. (Obviously, if both are possible, then I’m all for the free snacks.)

Oh, and when in doubt, as my best mentor once told me, remember that you’re hot shit.