Who Could Ask for Anything More?

Jeanine Basinger had never taught a film class in her life when she first arrived at Wesleyan on May 31, 1960. As the new marketing director of the University’s American Education Publications, she was focused on doing her job. But living in Middletown posed a serious problem: The only movie theaters in town were barn-like wrecks.

“Six months and I’m gone,” she promised herself.

Basinger hailed from Brookings, South Dakota, which boasted The College Theater, a cozy art deco jewel not far from the house where she grew up. “I was a hard-nosed filmgoer by the age of three,” she said. “My earliest memories are walking into dark movie theaters and looking up at the sparkling silver nitrate Technicolor movies that were being shown on the big screen when I was a little girl during World War II.” She loved everything she saw. She loved being there. “It was literally like going to a personal heaven,” she said, “entering a magical world that was all my own.”

At age 11, Basinger convinced her mother to let her work as an usher. It was then that she began to organize her attention, to understand what she was seeing. “When you stand on your feet at the back of a movie house,” she said, “and watch the same movie over and over, you begin to understand process. You see the way films tell stories, you see the effect they have on the audience, you see where they work and where they don’t. It’s the best way to learn—on the firing line. But in my day, it was literally the only way to learn.”

There were virtually no serious books on film; the few that attempted were pretentious. So, Basinger would have to seek out the information herself, firsthand. By the time she was a teenager, she was visiting film archives around the country, like Eastman House in Rochester, the Motion Picture Academy in Beverly Hills, and, in pursuit of firsthand knowledge, writing letters to stars and filmmakers, editors and grips, asking for interviews and, incredibly, getting them.

Building the College of Film and the Moving Image

So it was that Basinger arrived in Middletown deeply and uniquely versed in films and filmmakers. John Frazer, an experienced teacher in the art department but a comparative novice in film, suggested Basinger help him create a serious film course—what that meant, no one was certain. All that was certain, however, was that Basinger was the place to start.

At Frazer’s request, she sat in on a cinema studies experiment—an ad hoc seminar led by Frazer and English professor Joe Reed. The film they had chosen to screen for their small group of students was For Whom the Bell Tolls. “They were thinking it had to be good because it was ‘literary,’” Basinger said. But they were showing it in black and white.

“I’m surprised you’re showing it in a black-and-white print,” she remarked to Frazer, “considering Ray Rennahan shot it in color. And he was nominated for an Oscar for Best Color Cinematography.”

After that, Fraser invited Basinger to teach a course of her own. She would pick three iconic directors with three distinct levels of critical prestige and compare their films by genre. The class—Ford, Hawks, and Walsh—was one of Basinger’s first.

She had no professional teaching experience and had not prepared to become an academic; nobody could have predicted what happened next. Over the next half-century, Basinger would create a full-fledged film major, eventually growing it into a program, a department, and finally the College of Film and the Moving Image, which many regard as the strongest of its kind in the country: “a cinematic powerhouse,” in the words of New York Times film critic A.O. Scott, and “one of the wonders of the academic world: a department where students can learn film production, history, and theory while being held to the highest artistic and academic standards.”

But in 1969, no liberal arts college in America was offering a film major, not really. There were no PhDs in film; a couple of colleges gave feeble film “appreciation” classes and the few universities that did offer serious instruction in film were teaching only film production classes. Those like Martin Scorsese’s professor Haig Manoogian at NYU and Francis Ford Coppola’s professor Dorothy Arzner at UCLA were helping their students actually make films. But how productive would that be, Basinger wondered, if students hadn’t first been taught how to think about films?

“When I first started teaching at Wesleyan,” Basinger said, “I realized the students were fabulous. They had so much imagination, intelligence, originality. I kept thinking to myself, ‘Why don’t these people work in the film business?’ I told them, ‘Somebody gets those jobs in Hollywood. Why not you?’”

Frazer agreed to teach a production class in which, together, students made one short film, and Basinger became the professor of film studies, overseeing history and theory (Frazer later withdrew from teaching film production in 1990 to devote his time to the art department; Basinger assumed the responsibility).

“What you have to have is an understanding of how the medium of film works,” she explained, “and the ability to know how the filmmaker uses the medium to reach and speak to an audience. You have to have an awareness of how technique unites with ideas and content to make an effective film effective.”

As English students would close-read Shakespeare’s use of language and meter, Basinger’s film students would study Orson Welles’s use of camera placement and editing. They would learn to esteem films cinematically—that is, not in terms of their literary, theatrical, cultural, or political properties, but as works of film art. They would analyze style, not content. This approach, “Film as Film,” was, in those days, “a joke,” Basinger said. If pressed, professors of the late ’60s would concede to an Ingmar Bergman or Jean Renoir (or any foreign language film for that matter), but Basinger was showing her students films in English, without subtitles, films that, in many cases, could be comfortably classified as “movies.” She was showing her students Pickup on South Street, Kiss Me Deadly, and Day of the Outlaw. She was teaching Hollywood.

“What I’m teaching people is how to think,” she said. “I’m giving them a set of tools.” In the words of her former student, Benh Zeitlin ’04, Oscar-nominated director of Beasts of the Southern Wild, these are “the inner workings of visual language . . . the architecture of everything good you’ve ever seen. You come out of [Basinger’s classes] with pieces you need to build anything you can imagine.”

“Every great filmmaker defines the medium on his or her own terms,” she tells her students. The future filmmakers among them are quick to understand she may also be talking about them. “What she teaches you is about you,” says Joss Whedon ’87, Hon. ’13. “That everything you see is an expression of yourself, and therefore, eventually, everything you film is going to be the same thing.”

“In her classes,” says Bruce Eric Kaplan ’86, writer and co-executive producer of Girls, “she shows films that came out of the Hollywood studio system and shows again and again that it is possible to create high art in a commercial form.”

“One of her most extraordinary accomplishments,” says Larry Mark ’71, producer of Dreamgirls, Jerry Maguire, and As Good As It Gets, “has been not only to hang on to the popcorn for all of us but to add wisdom and perspective and insight to every kernel.”

Key to Basinger’s acclimation were the English department’s Joe Reed, a “major campus political influence,” she said, and the intellectual companionship of Professor Richard Slotkin of American studies.

“Richie was a great teacher, a great scholar, and a generous and supportive colleague. He became a dear friend and his help over the years can never be overestimated.”

Slotkin echoes the sentiment—and then some: “To say that her knowledge of American movies and the film industry is encyclopedic is to understate the matter.” The early endorsement of such well-established professors conferred some academic respectability on the fledgling discipline of film studies.

Stars Aligning

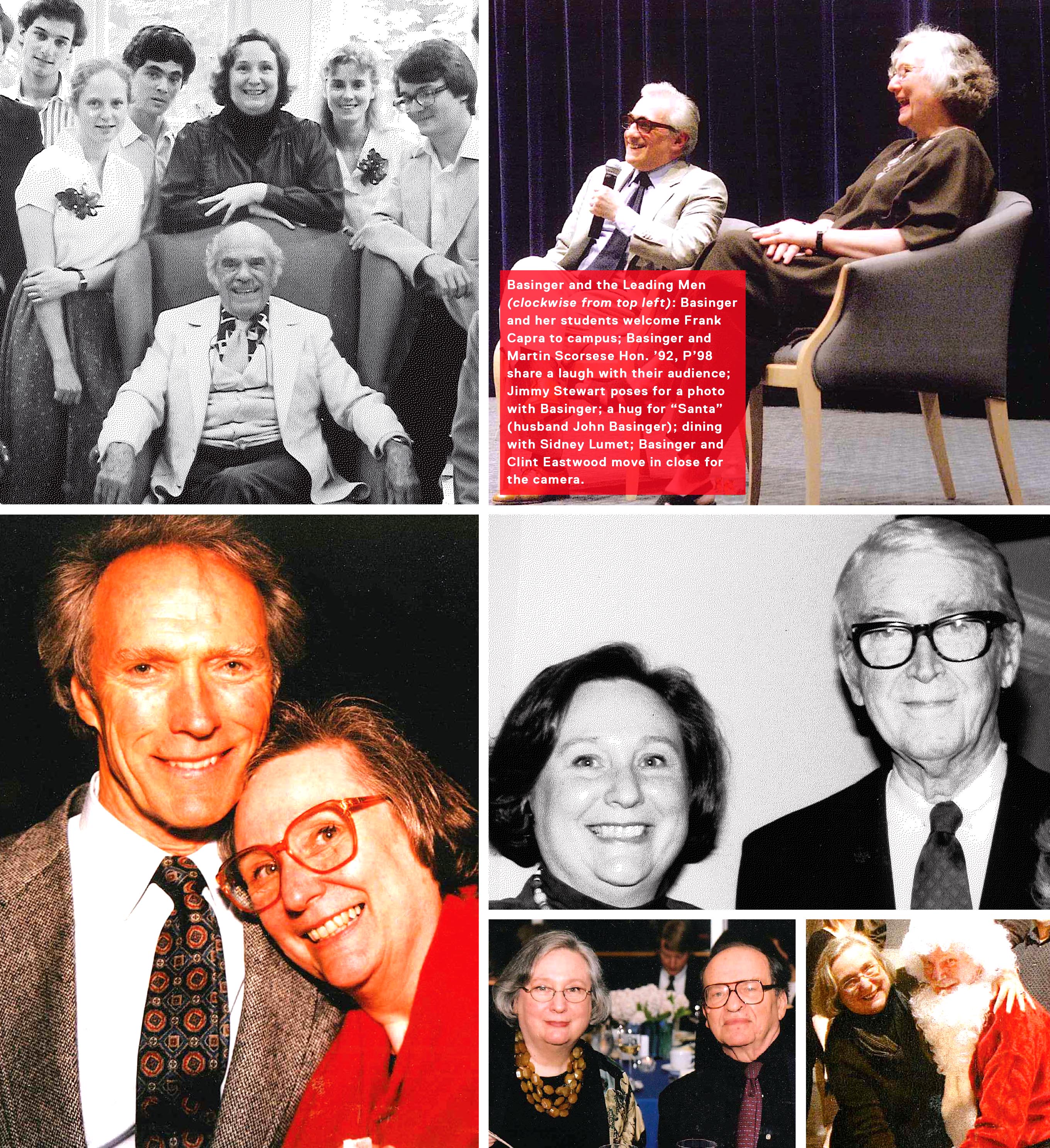

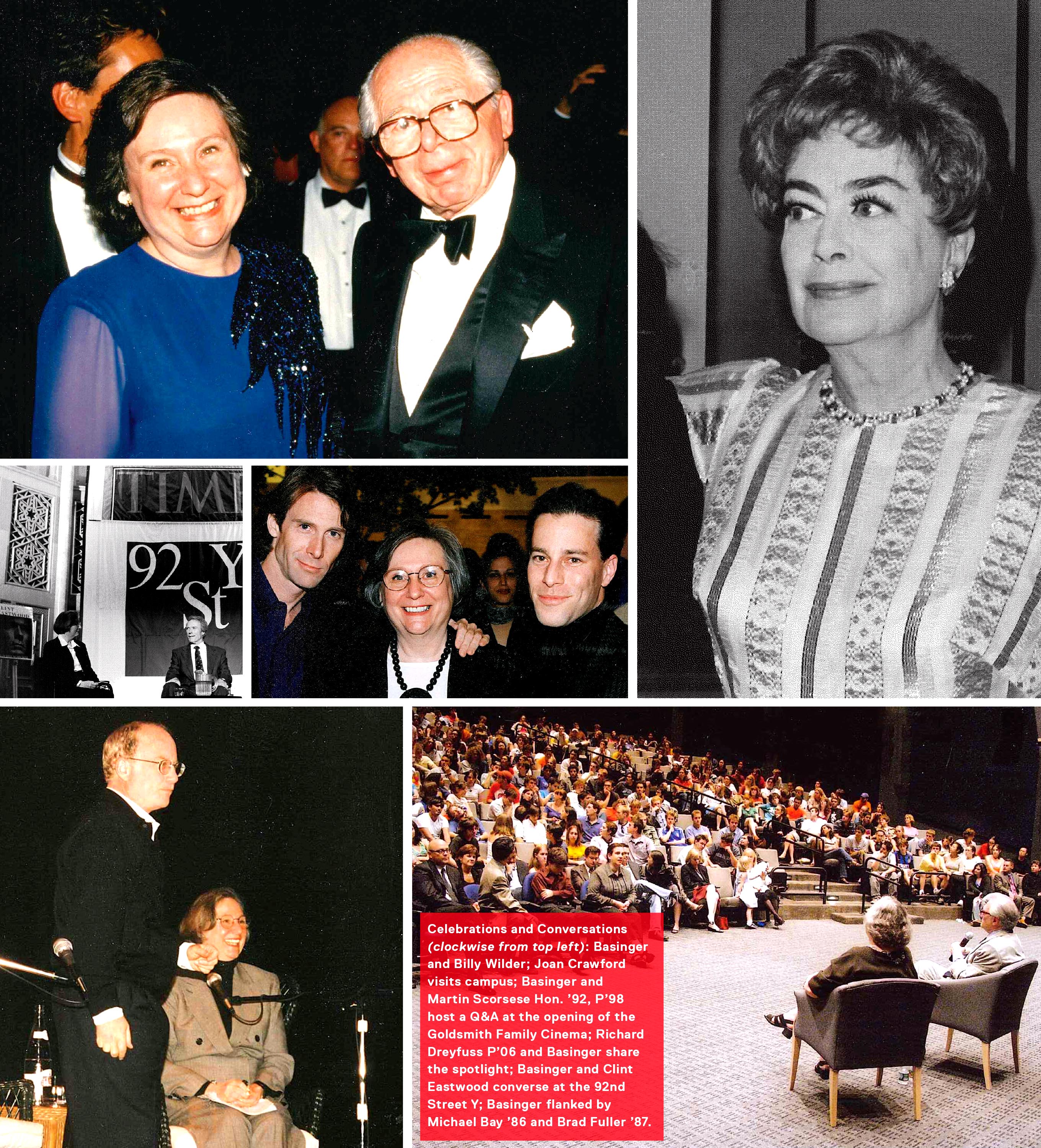

In 1970, Basinger and her student (future Oscar-nominated producer) Larry Mark created what would become the oldest continuously operational student-run film series in America. As co-programmer of important and hard-to-see films, Basinger was not only a crucial cultural influence in the Wesleyan community, she was an active ambassador of international cinema, inviting to Wesleyan the world’s greatest and most challenging filmmakers, beginning with France’s Alain Resnais, who brought to campus Hiroshima, Mon Amour in 1971. And where few in those years recognized the significance of Barbara Loden, Basinger invited the filmmaker to Wesleyan to screen her film, Wanda. Other giants, all friends and admirers of Basinger’s, followed: Raoul Walsh, Andrew Sarris, Sydney Pollack, Pauline Kael, Frank Capra, Nicholas Ray, Robert Wise, Sidney Lumet, Elia Kazan (who had already donated his personal papers to Wesleyan). “These people came at their own expense,” Basinger said, “because they were happy to be a part of educating young people about the business they had worked in all their lives.” (Basinger has since continued the practice, recently bringing to campus contemporary luminaries like Alejandro Iñárritu, Peter Farrelly, and Alexander Payne).

Impressed by Clint Eastwood’s directorial debut, Play Misty for Me, Basinger started teaching his work in 1971, long before the critical establishment recognized him as a director, let alone a director of major importance. More than gratified, Mr. Eastwood responded in kind.

“Jeanine Basinger has been a dear friend for many years,” he said. “And she is truly one of my favorite people. Her knowledge of cinema history and passion for film preservation is unparalleled and her books should be required reading for any aspiring filmmaker . . . or anyone who simply loves film. Speaking to her film classes is always a joy and a privilege. She’s just the greatest.” Eastwood would pay two visits to Wesleyan to speak with Basinger’s students.

As film studies grew in popularity, both at Wesleyan and in the academy at large, Basinger stayed ahead of the curve, creating the Women’s Film Festival to raise awareness of the image of women in film both behind and in front of the camera, and offering—the very year women were first admitted as full-time students at Wesleyan—an entire class on actress Joan Crawford. “I wanted to show how as she aged the roles had to be adjusted to the issues women faced.”

When The New York Times ran an unflattering interview with Crawford, Basinger wrote in. Arts and Leisure section editor Sy Peck was so impressed with her rebuttal—“Crawford has an image,” Basinger would explain, “and this person interviewed that image”—he asked Basinger to develop the letter into a longer piece. She did. At 7:20 in the morning the day the paper came out, Basinger was making breakfast for her daughter, Savannah, when the phone rang.

“Hello?”

“Jeanine? This is Joan.” The voice was unmistakable; she recognized it instantly. “You, my dear, are a very great lady,” Crawford continued. “And I am grateful to you beyond more than I can express for your kindness in presenting me as you see me, as a real person.”

Basinger invited her to speak with the students, and to her amazement Crawford accepted. It was the only campus appearance she would ever make.

“We became good friends, talked on the phone a lot,” Basinger recalled. “I would go in and visit her in New York. I still have the recipe she gave me for Jerusalem artichokes. Not that I ever cook.”

A Home for Film and Archives

As film classes grew into a major within the art department, and then into its own program, Film Studies, Basinger fought, explicitly and covertly, to keep extending its purview. Despite the popularity of her classes and the notable professional achievements of her former students in and out of Hollywood, Basinger regularly faced opposition from those at Wesleyan averse to the notion of film studies. Without the support and understanding of President Colin Campbell, she might have given up. Campbell was “one of Wesleyan’s greatest presidents,” Basinger said, and was “always open to innovation, always open to excellence.” But by and large, “it was a challenge.”

However, those qualified to recognize her ability were legion. In 1981, Frank Capra, director of It’s a Wonderful Life, It Happened One Night, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, donated his voluminous collection of personal materials (scripts, letters, photographs, sketches amassed over his six storied decades in film) to Basinger for safekeeping. Initially, Basinger housed the collection in the basement of the Center for the Arts, but soon saw that the location was inconvenient to visiting scholars eager to access the material. Where to put it? “There were very few archives dedicated to preserving primary documents,” Basinger said. “People just threw stuff away. You could find better primary documents if you were an Italian Renaissance scholar than a 20th-century film scholar! So, people began to address this and we were one of the first to put together serious collections from major filmmakers for archival study.”

Film was such a new discipline that Wesleyan had no funds allocated to Basinger’s classes. Nor were film materials like prints, projectors, projectionists, lights, cameras, and editing machines easy to afford. “It was the students,” she said, “that came to the rescue.” Basinger had the help of early supporters like John Goldsmith ’84 (after whom one of the film studies viewing spaces is named) and artist Toni Ross ’79, and, in short order, she inaugurated a fundraising campaign to establish an entirely new scholarly enterprise on campus: the Wesleyan Cinema Archives. Like the department itself, she would build it from scratch. “Make it like a home,” Frank Capra requested.

In 1983, her efforts secured the film department exclusive use of the wood frame Victorian house at 301 Washington Terrace. After extensive renovation and installation of archive-safe temperature and humidity controls and state-of-the-art fire and security systems, the building was formally dedicated on September 28, 1985. The archive was, as Basinger would say, “a way to attract prestige to the major,” but it was also, as Capra had requested, an actual home—with living room, fireplace, kitchen, dining room—a home for students, scholars, faculty; a home for film; a haven for study and enjoyment.

“The Archives is for you,” Basinger said to a gala-gathering of nearly 300 students, past and present. “It’s dedicated to you. You’re out there in a cold, cruel world and I wanted you to know that, no matter what, back here at Wesleyan you’ll always have a roof over your heads. . . . I’ll always keep a light in the window for you. But if you make lousy movies, I’ll turn it out. So keep that in mind.”

Joining Kazan and Capra, many of the world’s greatest filmmakers followed suit, donating their collections to the Wesleyan Cinema Archives: Clint Eastwood (“You can’t say no to Jeanine Basinger,” he said), Martin Scorsese (“Jeanine Basinger’s love of cinema and the people who make it is joyful and infectious; it’s overflowing”), John Waters (“Just look at the Wesleyan Archive [Basinger] created. Who would have thought that Dirty Harry’s badge and Divine’s fake vagina would be side by side in the same collection?”), Federico Fellini, Gene Tierney, Jonathan Demme, Ingrid Bergman, and countless extraordinary others.

“My mother, Ingrid Bergman, kept all her letters, diary, posters, scripts,” explained Isabella Rossellini. “When I asked her why she did it, she answered: ‘Film is the most popular art form of the last century. I know I worked with the biggest talents in the industry, yet unlike paintings, sculptures, literature, there are no structures to collect the history of this new art form. Maybe one day someone will come up with a solution.’ Jeanine came up with the solution.”

Basinger and Film’s Lasting Legacy

That Basinger’s students have consistently risen to the highest levels of every aspect of film and TV production in and out of Hollywood, that they have succeeded outside academia in the “real world” as actors, directors, editors, producers, and writers, is a feat they attribute to embracing the simplicity of Basinger’s approach. As American film critic and historian Leonard Maltin put it, “Jeanine’s ability to communicate on both levels—as a fan and as an academic—is what makes her so special.”

“Jeanine is a legend in inspiring people,” says Michael Bay ’86. “She may look like your great aunt who bakes the best apple pies, but she is the badass of film knowledge and the biggest inspiration of my film career. Coming in second, tied, are Steven Spielberg and Jerry Bruckheimer.”

By 1990, into Basinger’s third decade at Wesleyan, Film left the art department to become a separate program and a standalone major, cross-listing with other departments to offer a wide range of courses not just in Hollywood film, but the international cinemas of Japan and France and (taught by Professor Ákös Öster) the films of Africa, India, and Australia. In 2000, Film became officially a fully recognized department and began hiring its own faculty. Today, even President Michael S. Roth, continuing the tradition of interdisciplinary film at Wesleyan, teaches his own class: Philosophy and Film.

“By the time you leave her program,” says filmmaker Miguel Arteta ’89, “you’re certain that your own personal and twisted observations about how people behave will become your greatest weapons for success.”

Outside of Wesleyan, where Basinger is Corwin-Fuller Professor of Film Studies, a two-time Binswanger Teaching Award recipient, and the only chair the department had ever had until Scott Higgins took over the role in 2016, she is the face of American film history. She serves as advisor to Martin Scorsese’s film foundation project, The Story of Movies; she consults on countless documentaries; and she has averaged, to date, 88 major media interviews a year for the last 20 years. She has produced an American Masters special on Clint Eastwood and was head consultant and producer of PBS’s American Cinema: 100 Years of Filmmaking, for which she also wrote a companion volume. Basinger was made a trustee of the National Board of Review, a trustee of the American Film Institute, and a member of Warner Brothers Theatre Advisory Committee at the Smithsonian Institution. Basinger’s credentials are impossible to list in a single place, but bear an attempt anyway. . . . Her book, Silent Stars, won the National Board of Review’s William K. Everson Prize, and The Star Machine won the Theatre Library Association Award. Voluminously cited and appearing as standard texts in film curricula across the country, these and her other books (to name but a few, A Woman’s View, The World War II Combat Film, Anthony Mann, and the forthcoming Musicals!) are simply unsurpassable works of film history; they radiate with Basinger’s native warmth, wit, staggering erudition, and common sense, and are indispensable to both the novice and connoisseur—and in the words of her editor, the legendary Robert Gottlieb, “smarter than all get-out and more fun than a barrel of monkeys—like Jeanine herself.”

Exactly 60 years after first arriving at Wesleyan, Basinger will retire in 2020. Her successor, Professor Scott Higgins, has already been chosen, and has already delivered on his promise. “He’s the right person to take my place,” Basinger said, “and everyone is happy with the choice.” In Basinger’s view, Higgins is the ideal leader to bring Wesleyan Film (now the College of Film and the Moving Image) into the next generation and beyond. “Scott will expand on what I built,” Basinger said. “He will go forward in the fields of game design, virtual reality, 3D, issues of internet distribution, and will continue the practice of teaching film across global perspectives, ensuring diversity and inclusion.” Higgins will be the beneficiary of the Mellon Endowed Center for Film Studies’ construction Phase Three, the culmination of Basinger’s 25-year-long labor and vision to build a state-of-the-art home for film studies. Phase Three—which will include a sound stage, an additional screening room, classrooms, offices, increased archival space, and designated spaces for the new Wesleyan Documentary Project—will be named for her.

“It took 20 years of studies, reports, and bureaucratic battles to begin to establish Film as an independent curricular entity,” Slotkin recalled. “And another 20-odd to develop Film Studies in its present curricular and institutional form. That Jeanine was able to accomplish all that, while maintaining an extraordinary quality of engagement with her students, and still produce a series of major scholarly works, is (to anyone who understands how universities really work) simply astounding.”

“Every day for 60 years,” Basinger reflects, “I have been surrounded by youth, energy, intelligence, talent, and commitment. As the Gershwins put it, who could ask for anything more?”

Sam Wasson ’03 was an English and film studies major at Wesleyan, and also attended the USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has since published five books, including the best-selling Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M. and the award-winning Fosse, in addition to numerous other publications in The Hollywood Reporter, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Yorker.