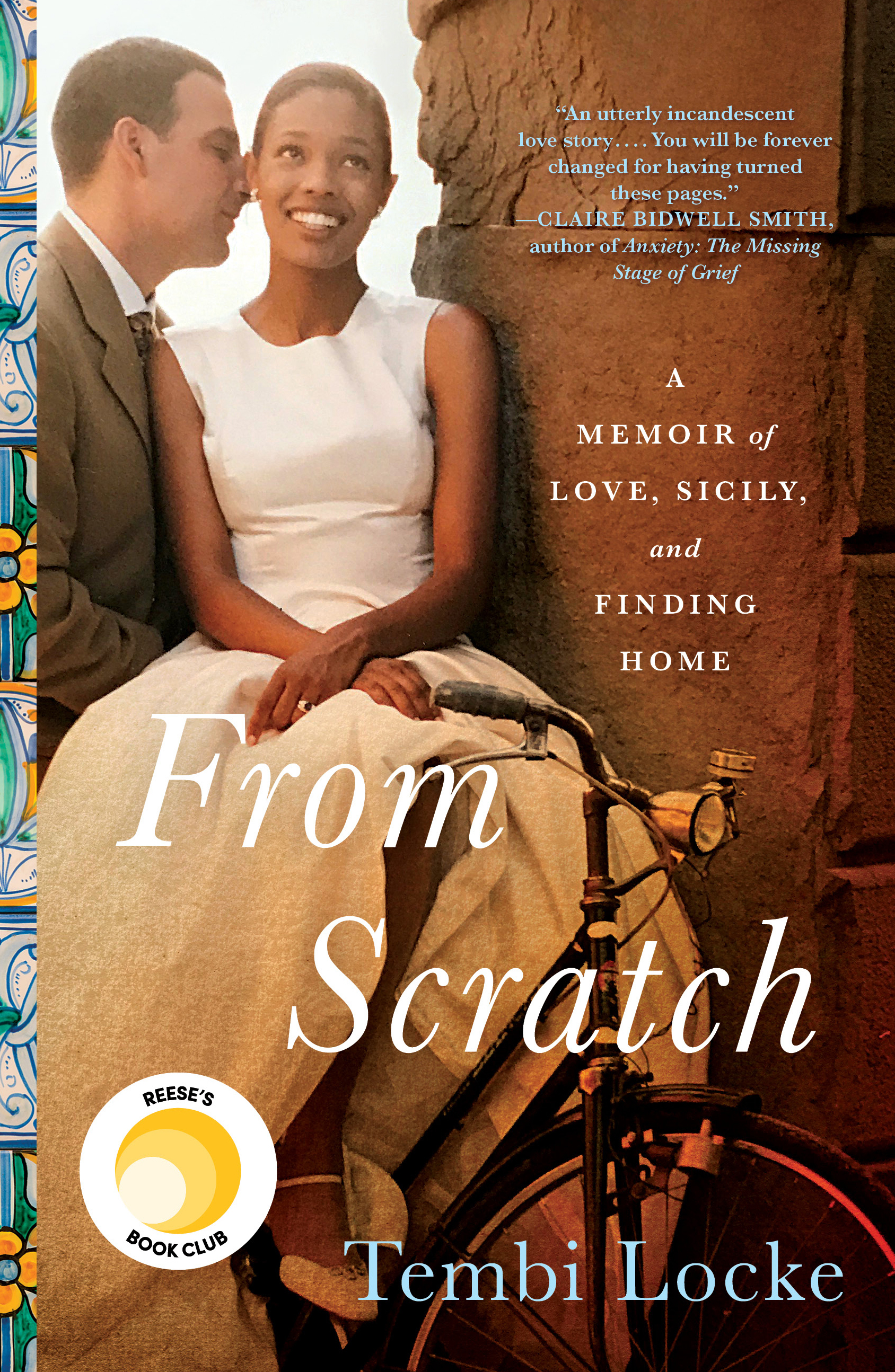

From Scratch: A Memoir of Love, Sicily, and Finding Home

In an excerpt from her new memoir, Tembi Locke ’92 details the moment when you realize that a formerly foreign place is now a treasured part of who you are.

Three summers after the death of my husband, the phone rang one sweltering July afternoon in Sicily. It was during siesta in my mother-in-law’s home, which is nestled in a small town in the island’s rural interior at the foothills of the Madonie mountains. She called to me in her native Sicilian and told me there had been an accident in town with an English tourist. As the only person who spoke English, in this hamlet of small-parcel farmers and a single church, I was being called upon to translate. And, as my mother-in-law hinted, de-escalate a growing situation.

Minutes later, I emerged from a narrow pass-through between two streets, surprising a middle-aged blonde man in a linen shirt with sweat stains, his nerves frayed. We quickly exchanged pleasantries and intros the way people of the same tongue in a foreign land can do. He was on holiday with his young family. He had come into town to get bread, only to find that everything was closed. The man whose car he had hit, I soon discovered, was Calogero, the affable farmer with a hearty laugh who gave me lentils each year from his field to take back to my home in Los Angeles.

As soon as Calogero saw me, he jumped to the quick “Parla con quello!—Speak with that one!” Then he threw his arms up in the classic Sicilian gesture signaling frustration, resignation, and rising indignation, a movement that told me everything I needed to know.

Before I could translate, the Englishman rushed to his own defense. He was adamant that Calogero had been at fault. One look at his rental car, and it was clear that he was probably right.

I asked him if we could speak away from the growing crowd.

“The man you are accusing of hitting the car is the mayor’s cousin,” I said. I was jumping to what seemed to me the most salient piece of information he needed to know.

He looked at me confused and irritated, as if to say, what does the mayor’s cousin have to do with anything?

After years of coming to Sicily, I was thinking like a Sicilian, which means considering the social hierarchy of a particular situation before the facts.

“Let’s go inside,” I said, pulling him toward Calogero’s front door.

Inside Calogero’s intimate, immaculate kitchen, three generations of a family gathered at a kitchen table to testify to the innocence of their relative. We all sat at a plastic-covered table for four. Each man reconstructed their version of the accident on the back of a napkin. A traditional Sicilian ceramic light fixture with a painted illustration of Moors and grapevines hung above us. A crate of tomatoes sat on a nearby chair, likely waiting to be boiled into submission.

I went back and forth between English and Italian, translating both language and culture for an Englishman who was suddenly realizing that the deck was stacked against him. Here people would never betray one of their own. Whatever had actually happened was, in fact, irrelevant.

“You are not in Tuscany, you are in Sicily,” I said, reminding him that Italy was not a monolith and Tuscany was not a stand-in for a whole nation, despite what cinema might suggest. Sicily, especially the rural interior, had scant tourist infrastructure. English was not prevalent, and locals were not casting their gaze outward, inviting the world in.

“I see that now.”

Then he turned to me, and, perhaps for the first time in the hour we had been together, he saw me—a black American woman seated at the table among the faces of people she neither resembled nor defended but whom she seemed to understand.

“How the hell did you get here?” he asked.

I gave him the only answer that would explain it all: “I was married to a Sicilian man. I’m now his widow.”

He lingered for a moment, as if trying to process the sequence of life events I had laid out. Then he offered his condolences. Ten minutes later I got him to agree not to pursue the insurance claim issue any farther.

“Tell them your car was hit while it was parked. No one’s fault. Pay the fine, and enjoy the rest of your vacation,” I said.

“It’s a beautiful place,” he said referring to the rolling fields that led to the valley below. “But I can’t say that I will be coming back. These people don’t make it easy.” I wanted to educate him about the fact that he was on an island that has been conquered and ruled by many outsiders throughout history. That the Sicilian instinct isn’t always to make it easier for an outsider.

Later, I watched him drive away, up the winding road past the blackberry brambles, taking the series of curves that would lead to the country house he was renting. I was ready to go back home too. Not to Los Angeles, but to the home I had found in a place where streets have no names, where I had scattered ashes, made cheese, and hung underwear on the line to dry. It had taken a marriage and then a death, but I had found home in an unexpected place.

Excerpt reprinted by permission of Simon and Schuster.