Leadership in 15 Languages: Helping Prep the Next Generation of Polyglots

Wesleyan has an unusual language requirement in that there isn’t one. But while students are not mandated to take a language in the open curriculum, nearly 70 percent of graduates over the last 10 years have done just that. The high enrollment reflects something of a well-kept secret: Wesleyan students are interested in language and Wesleyan faculty are adept at teaching it.

“Wesleyan is a place where opportunities are not forced on you,” said Stephen Angle, Mansfield Freeman Professor of East Asian Studies and director of the Fries Center for Global Studies. “You explore, you find something you’re excited about, and then you do it in a deep way. A big part of our mission at Fries is to promote opportunities for students both to learn and to use language, and provide a platform where those rich intercultural learnings can take place.”

The Center has started tracking and analyzing robust data about language and intercultural learning at Wesleyan, leading to some impressive findings and allowing the University to provide better and more unified acknowledgment of and support to its many language students.

While preparing the Fries Center’s annual report last spring, Director Steve Angle and Assistant Director Kia Lor made a surprising discovery: With formal classroom instruction in 15 languages, Wesleyan offers the most language courses of any coed liberal arts school in the country (by comparison, Wellesley College also boasts 15; Middlebury College, commonly recognized as a leader in language instruction, has 13).

“We’d known all along that we have a high number of language courses, but until we actually sat down and counted them, I don’t think anyone realized that we had the most,” Angle said. “It was like discovering a great jewel in your attic that you never knew about.”

The finding is particularly striking due to the fact that, unlike many peer institutions, Wesleyan has no language requirement. And that may be precisely why Wesleyan’s students are so linguistically minded.

“I think our open curriculum and the freedom to choose to study a language allows students a greater depth to their studies,” Lor said. “Some students are taking multiple languages, even though English may be their second or third language.”

The popularity of studying abroad is undeniably tied to this point. Any student planning to study in a country whose language is taught at Wesleyan must first complete coursework in that language.

Whatever the reason, there’s no denying that languages are a critical element of the Wesleyan academic experience for most students. Over the last 10 years, 60 to 70 percent of each graduating class has boasted language credits. Among 2019 graduates, 30 percent had studied a language at an advanced level.

“Students understand that language is a powerful entry point to culture,” Lor said. “If you understand a language, that allows you to understand a world view that you would not otherwise be able to access.”

New Additions

The landscape of language learning has changed dramatically over the past few decades. Gone are the tape recorders and headphones. In some cases, classrooms aren’t even necessary.

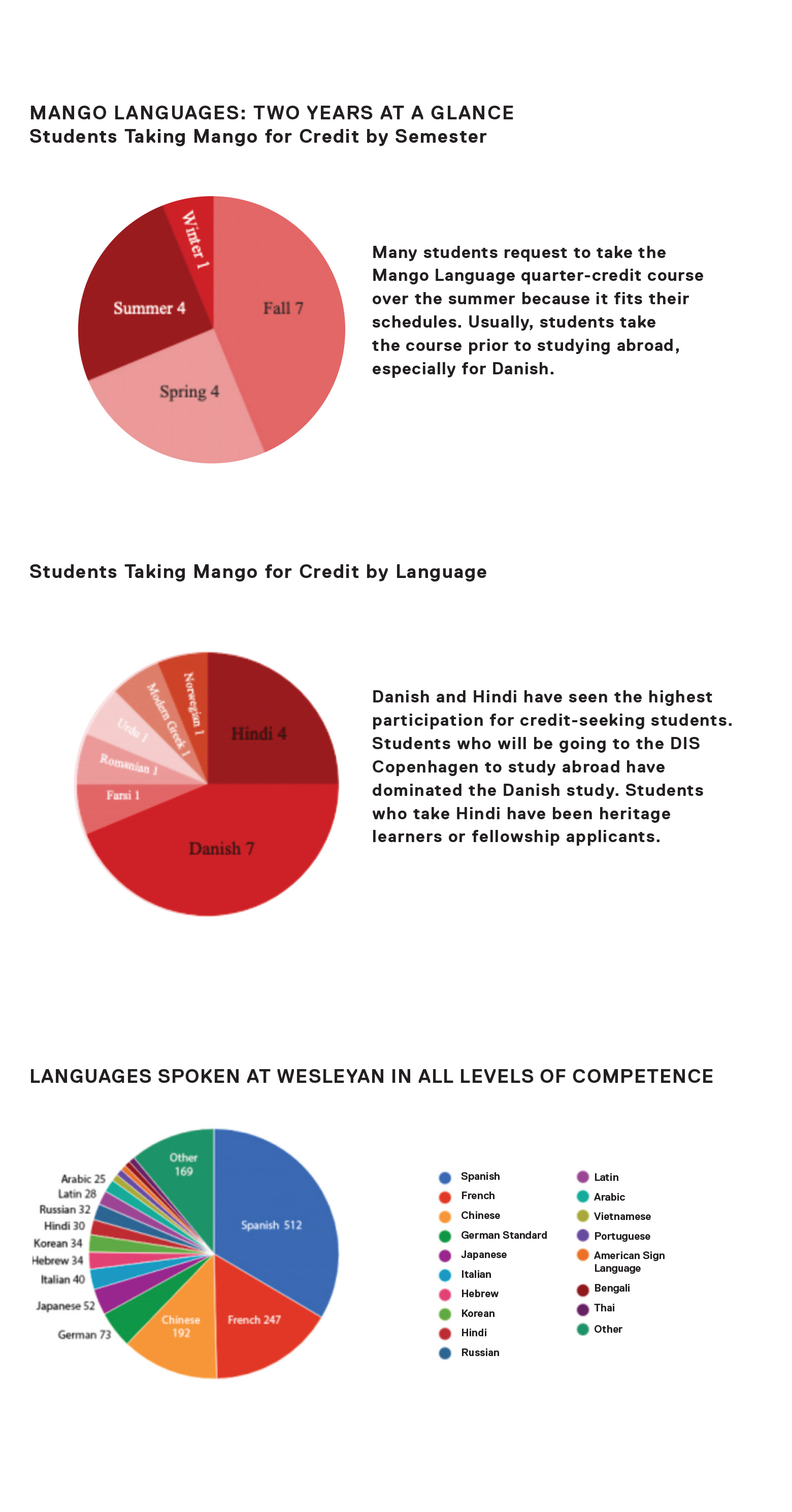

Take, for instance, Mango Languages, a digital language instruction program in more than 70 languages and dialects. Accessible online or through an app, Mango enables users to develop proficiency anywhere, at any time, with interactive reading, writing, and listening exercises. Wesleyan began offering students, staff, and alumni free access to Mango in 2016. Since then, 18 students have taken Mango courses for credit. (Nearly 500 Wesleyan users accessed Mango for non-credit learning as well.)

Often, Lor says, students log on to Mango to prepare for study in a country whose language is not taught at Wesleyan. Danish, for example, has been popular among students traveling to Copenhagen.

Mango’s programs also come in handy for students who are applying to the US Department of State’s Critical Language Scholarship Program, seeking professional development, or learning a heritage language. It’s just the latest addition to Wesleyan’s suite of “less commonly taught languages” offerings, which also include American Sign Language courses (taught on campus by visiting instructors) and Self-Instructional Language Program tutorials (directed by faculty members of other institutions and supplemented with in-person native-speaker sessions in languages such as Swahili, Farsi, and Modern Greek).

Regular course offerings have expanded, too: Wesleyan’s first Hindi-Urdu classes kicked off in September, with seven students enrolled. Taught by Assistant Professor Hafiz-Muhammad FazaleHaq, and funded through a grant from the US Department of Education’s Undergraduate International Studies and Foreign Language Program, the elementary and intermediate courses prepare students for real-world interactions with Hindi and Urdu speakers (a population of hundreds of millions).

Beyond the Classroom

The University helps students hone their skills in social settings, too. During the 2018-19 academic year, nearly 200 campus events occurred in languages other than English, including weekly conversation lunch tables, film series, festivals, and game nights. The Fries Center is a central hub for these activities; its creation helped spur the formation of the Lead with Languages Collective, a group of more than 30 faculty members who aim to cultivate a multicultural campus with a strong language learning presence.

The Power of Language Conference, organized by students and the collective, is a testament to these efforts. Entering its third year in 2020, the conference—open to the Wesleyan and Middletown communities as well as other local universities—celebrates the diversity of languages on campus (more than 80 are represented). Conference presenters have shared a range of projects, including senior theses and personal reflections on navigating life as a multilinguist.

Last year, alumni presenters discussed how they’ve used foreign language skills and the associated competencies gained through their study in the workforce. For many, learning languages represents acquiring “the cognitive ability to be a child again—to learn something completely new,” Lor said. “How does that translate into a new job, or medical school, where you have to learn new terminology?”

In fact, that open-minded approach is being applied by graduates across a broad swath of fields, including education, law, diplomacy, public service, business, communications, medicine, and finance. Alumni work as translators and interpreters, financial analysts and international consultants, artists and filmmakers.

As a next step in its research into language studies at Wesleyan, the Fries Center (with the help of the Gordon Career Center) is interested in further tracking the careers of language-learning alumni, Lor said. Like the project to compare Wesleyan’s formal language offerings with those of its peers, analyzing graduates’ outcomes could yield some surprises.

One thing’s for certain, though, Lor said: “Those who are committed to language learning care so passionately about it—even after they leave Wes.”

CAPTION (photo at top): FCGS staff include (clockwise from top left) Stephen Angle, Emily Gorlewski, Emmanuel Paris-Bouvret, Konstance Krueger, Kia Lor, Magdalena Zapedowska, Hannah Parten, Jennifer Collingwood, and (not pictured) Alice Hadler.