(Not So) Lost in Translation: Study Abroad Sets Students Up for Immersive Cultural Experiences

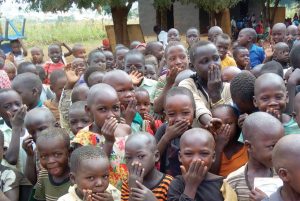

Photo of Cap Est, Madagascar, by Katie Toner ’20

It’s a common image on movie screens, in vacation videos, and in social media feeds the world over: the eager young student, set against the backdrop of a stunning foreign landscape, looking travel-weary yet energized with the light of new understanding.

The prevalence of these Instagram-friendly portraits makes it easy to dismiss the experiences behind them as self-indulgent or the purview of the privileged. But at Wesleyan, where 40 percent of undergraduates participate in some sort of study abroad, students are pushing back against the stereotype and embracing the benefits of changing your environment, challenging unconscious bias, listening to different perspectives, and yes, even “finding yourself.”

The Language Barrier

A key element of Wesleyan’s study abroad program is the mandatory language policy—an uncommon practice among universities offering global studies. Students must either take classes in the target language or meet language prerequisites for their specific programs.

“The language policy is strict, but it leads to incredible learning for the students,” says Associate Director of Study Abroad Emily Gorlewski. “Students who are really dedicated to speaking the language can have a much deeper, richer experience because of it. And having at least a basic grasp of the target language allows students to interact in a more respectful way with the host culture.”

Wesleyan’s open curriculum makes the requirement all the more noteworthy, since there is no core language requirement for the University itself. It’s a policy based on choice, the bedrock of liberal arts learning, and ensures that students who choose to study abroad do so purposefully, intent on getting the most out of their time in the program. Plus, a baseline level of fluency allows students to focus on more sophisticated and nuanced cultural interactions.

For earth and environmental sciences major Avery Kaplan ’20, studying in Valdivia, Chile, was initially meant to be her “semester to focus on Spanish.” But some of her most important realizations came in the moments when she wasn’t speaking.

“So much transcends language,” Avery said. “The things that don’t translate well are turns of phrase and jokes; small talk and bantering are more difficult. But one-on-one connecting with someone is much easier than you think. I found myself in the position of listening much more. And I realized that for us as English speakers, it’s important to have that time to think and reflect, and to have the experience that so many non-English speakers have in the US. It taught me not to take language or understanding for granted, and to empathize more.”

Even for those students who travel to countries where learning a new language is not necessary, the benefit of pursuing their studies in a context-specific location adds a new dimension to their critical analytical skills.

“As an English major, I loved being able to study literature from England in the place it was born,” wrote Zoe Kaplan ’20 of her King’s College program. “Shakespeare’s London literally grounded our studies of Shakespeare’s work in our physical place as we interacted with the streets and stages of his city. [Study abroad] allowed me to not only pursue the subjects I love, but also engage with them by placing them in new contexts relevant to the country I was studying in. As I continue with my education—and life—after King’s, I try to practice this critical skill, broadening my focus beyond the texts I study and situations I’m in by working to understand their contexts to enrich and develop my perspective.”

Study Abroad for All

With more than 350 students participating each year, study abroad is already ingrained in Wesleyan’s culture. Still, Gorlewski is on a mission to ensure all students are aware of the program’s accessibility. Sponsoring workshops and pre-orientation sessions; having abroad credits count toward their degree; instituting a home school tuition policy that allows students’ financial aid to be applied toward approved semester programs—all serve to encourage students to explore the global community and assure them that study abroad is not a perk reserved for the rich or overly ambitious.

The bottom line: If you can afford Wesleyan, you can afford study abroad. And inclusivity is especially important because, for so many students, doing research in other countries is an irreplaceable advantage in pursuit of their overall academic and career goals.

When Jericha Major ’20 signed up for the SIT Madagascar—Biodiversity and Natural Resource Management program, she was excited to experience fieldwork for the first time, and in a geographical area that was “uniquely diverse but also so vulnerable to climate change.” Through weekly trips around the northeast region of the republic, she learned about a range of environments, ecosystems, and inhabitants that were completely new to her. “At the end of my time in Madagascar, I also had the chance to create my own independent study project. Although it was challenging at times, designing and conducting my very own marine science research was unforgettable and extremely useful.”

Success stories with their start in study abroad include Max Perel-Slater ’11, who studied in Tanzania, returned there to do a College of the Environment capstone project, and returned again to start the Maji Safi Group, providing disease prevention and menstrual health management education in rural Tanzania; and Jessica Posner ’09, who studied abroad in Kenya, where she met Kennedy Odede ’12, and together they built the Kibera School for Girls and the Johanna Justin Jinich Clinic in Kibera as part of their SHOFCO program. Jessica is currently the CEO of Girl Effect, a nonprofit organization for girls’ empowerment based out of London.

Stripping Away Cultural Bias

Navigating complicated relationships between theory and practice, culture and geography, history and politics—all while in an unfamiliar environment and as a non-native speaker—yields an expanded perspective that many students can’t fully access from the safety and comfort of the Wesleyan campus. Reflecting the wide range of students’ intercultural awareness, some choose locations specifically to challenge themselves in this way, while others find it to be a secondary (but no less important) benefit alongside their more targeted academic pursuits.

“The most unexpected outcome from my study abroad experience was how drastically it challenged my beliefs,” Jericha said. “I came into the program keen to discuss the best forms of conservation for the prevention of species extinctions, such as the endemic lemurs. After working directly with Malagasy conservationists, farmers, ecologists, and more, I began to realize the complexities of conservation biology. Many class discussions with my study abroad peers highlighted the realities of residual colonization and the white-domination of conservation. The opportunity to witness environmentalism through a new perspective was transformative, and continues to shape my own conservation ethics today.”

Even for students who are used to navigating cultural difference, new environments provide new opportunities to check the expectations and unconscious privileges that may have seeped into their everyday lives.

Anushka Singh ’20 spent the first 10 years of her life in the United States and is an American citizen. But in middle school, her family moved to India and her parents now live in Mumbai. A government and economics major, Anushka petitioned to study in Havana, Cuba, during her junior year to learn more about the country beyond the history told from the American perspective. When she found herself unable to return to Havana after a weekend excursion, and arguing with the flight director that she had paid the equivalent of $40 for a ticket (whereas others had paid much less because they were citizens), she realized her own American-grown expectations had little currency in Cuba.

“He was like, ‘This is Cuba. It doesn’t matter how much you paid, you have to wait with everybody,’” Anushka said. “And I think that was interesting to hear because I realized my mind has been so wired to think: the more you pay, the better benefits you get. You should be able to get ahead. But it doesn’t always work like that.”

A Sense of Place and Reflection

The Office of Study Abroad sums it up best: “A meaningful cross-cultural experience sharpens our understanding of ourselves in relation to the world in which we live. It is the best means for achieving the intercultural expertise and multilingualism that our students will need for exercising leadership in an increasingly interconnected world.”

Part of that understanding and interconnectedness means making sure that students are active, productive participants in the countries they are visiting, not just tourists or observers. For some, this simply means developing authentic relationships with host families and friends and exchanging cultural learning. For others, it could mean joining fellow students in strikes aimed at effecting change in their host countries. For one lucky student, it was as simple as working the land.

“For two weeks before my formal study at University of Otago [New Zealand] began, I lived with the Wimmer Family in the Waitetuna Valley on the North Island,” said Miles Brooks ’20. “I found out about their farm through WWOOF, an organization that connects farmers to farmhands. In return for room, board, and food, I worked four-to-six hours a day. While there, I learned about permaculture, designing a sustainable lifestyle, and pottery-making, while spending the day in the garden or pottery studio. I helped out with cooking and taught them what I knew about beekeeping.”

While not all study abroad experiences can be quite as idyllic, Gorlewski hopes that students at least “think more about their place in the world. I want them to better understand who they are, understand global systems, and the place of the US or their particular home culture. To situate themselves in the world and realize how they can do things to benefit people a little bit more.”

And those wanderlust-inducing photos posted on social media? They’re part of the process too.

“It’s really the reflection part of the experiential learning cycle,” Gorlewski said. “Students can’t just put them in a box and be done. They have to process through it. And even if they did have what might on the surface look like a touristic experience, there’s something that they took away from it, and they might not realize it until they do this kind of reflection.”

“It’s a common reaction around Wesleyan to say, ‘Oh, study abroad changed you’ in a sort of patronizing way that diminishes the experience,” said Avery. “And I get it, because study abroad can be fraught with notions of privilege and there’s a tension between learning and being part of a community and also being an outsider tourist, which has voyeuristic connotations. But it really does change you. You can’t live in a foreign country for six months and not be changed by it.”