“Gandhi and Guerrilla”: Present-Day Echoes of the Mayday Protests

Debates over Black Lives Matter tactics and approaches to public dissent have parallels in historic civil disobedience in Washington, D.C.

By Lawrence Roberts P’11, Koeppel Fellow ’12

Every so often, when the republic seems to be racing headlong down the wrong track, a simmering social movement flares into a phenomenon. People set aside more temperate means of dissent and head out into the streets in huge numbers, demanding a radical shift in national direction.

It’s also the case that such mass actions spark a debate about tactics: What kind of demonstrations are appropriate for the times? How far should participants go in risking arrest or resisting law enforcers? That’s true in the present day, as the Black Lives Matter protests against police violence and structural racism spread around the country, and it was true a half-century ago during America’s largest act of civil disobedience, the Mayday protest of 1971 (also known as May Day).

It happened in Washington, D.C., during the administration of Richard Nixon, who continued to wage the Vietnam War even as public opinion turned against him. A group calling itself the Mayday Tribe planned an audacious action to demand that Nixon bring the troops home: a blockade of the city’s streets, bridges, and federal buildings. The Mayday slogan: “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.”

One architect of Mayday’s tactics was a radical pacifist named David Dellinger, a Massachusetts native and Yale graduate. Then 55, he saw himself as older brother to a movement dominated by people in their teens and twenties. Long before Vietnam, he drove an ambulance in the Spanish Civil War, was imprisoned for refusing to register for the draft, and picketed against nuclear weapons. He preached action in service of a cause, but only through nonviolence. His personal pacifism had to be absolute, even if it caused him serious injury. Which is exactly what it did one day in 1951.

At a rally against the Korean War, Dellinger stood in front of an enraged passerby, whose son had died in the conflict. Dellinger put his arms by his sides and said, “Go ahead and hit me if it will make you feel better.” The man did, knocking Dellinger to the ground and then kicking at his head, breaking his jaw and causing permanent damage to his right eye.

Dellinger was among antiwar leaders indicted for conspiracy to incite riots at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. The case made him a celebrity, and he gave speeches at colleges around the country, including Wesleyan. A couple of years later, he and Rennie Davis, another member of the Chicago Seven, decided it was time to escalate, as they put it, from mere protest to resistance. For six years the movement had mobilized millions of people to march against the war. It had launched student strikes that shut down hundreds of schools, sent peace candidates to Congress, and forced Nixon’s predecessor, Lyndon B. Johnson, to forgo re-election. And yet, not only was the war still grinding on, but Nixon had expanded it into Cambodia in 1970 and then into Laos in 1971.

So, Dellinger and Davis barnstormed campuses to promote Mayday. Some on the movement’s radical fringes scoffed, favoring violent confrontation with police, even bombings. Many in the mainstream also shied away, fearing a deadly backlash. They further argued that the appropriate use of civil disobedience was to violate a specific unjust law—such as segregated lunch counters—passively accept the consequential arrests, and go to jail to gain attention through a kind of martyrdom. In their judgment, the people who did this correctly in the antiwar movement burned their draft cards or refused to pay federal taxes that funded the military.

Dellinger had long held another view, a blend of “Gandhi and guerrilla.” He believed in confronting injustice through a symbolic violation, rather than only breaking the law you opposed. That could involve trespassing or blocking traffic. It offered dissenters an option beyond passive parades, but short of violence.

“It’s necessary to use force if you’re going to have an impact,” he said. “But there’s a difference between force and violence; they can and must be separated.” Black Lives Matter protesters have walked a similar line, blocking highways and bridges, in the face of similar criticism of their methods.

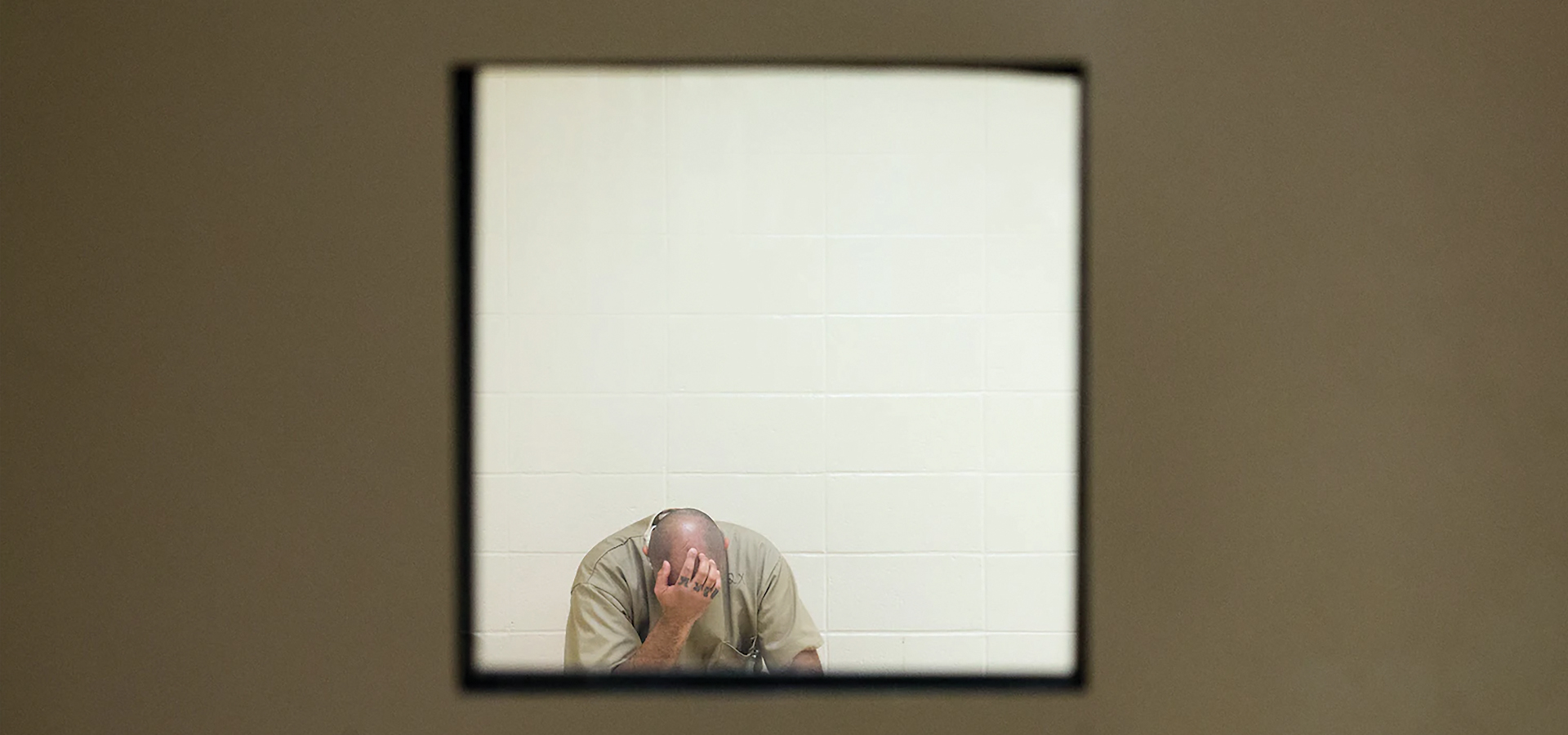

Tactics that history might judge as justified—even heroic, in the case of the 1960s civil rights movement—are rarely seen that way in the moment. Tens of thousands of people showed up in Washington for Mayday. They were greeted by a police dragnet that scooped up more than 12,000 people in three days, the largest mass arrest in U.S. history. Courts later declared the busts unconstitutional and ordered the government to pay millions of dollars to the detainees.

There had been scattered property damage on Mayday and many injuries from police batons and tear gas, but Dellinger’s pledge of nonviolence was kept. As for Dellinger himself, he missed the action. He was in a D.C. hospital room, being treated for severe eye pain stemming from his 1951 injury. His purity had cost him a chance to witness the events he dreamed into existence.

Dellinger never stopped protesting and writing about his causes. In 1997, his grandson, Seth, a junior at Wesleyan, invited him back to campus for a speech in the Science Center about nuclear disarmament. David Dellinger died in Vermont in 2004.

Lawrence Roberts P ’11 is the author of Mayday 1971: A White House at War, a Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020). In 2012, he was a Koeppel Fellow at Wesleyan. He has been an investigative editor with ProPublica, the Washington Post, Bloomberg News, and the Huffington Post Investigative Fund, and was a leader on teams honored with three Pulitzer Prizes.