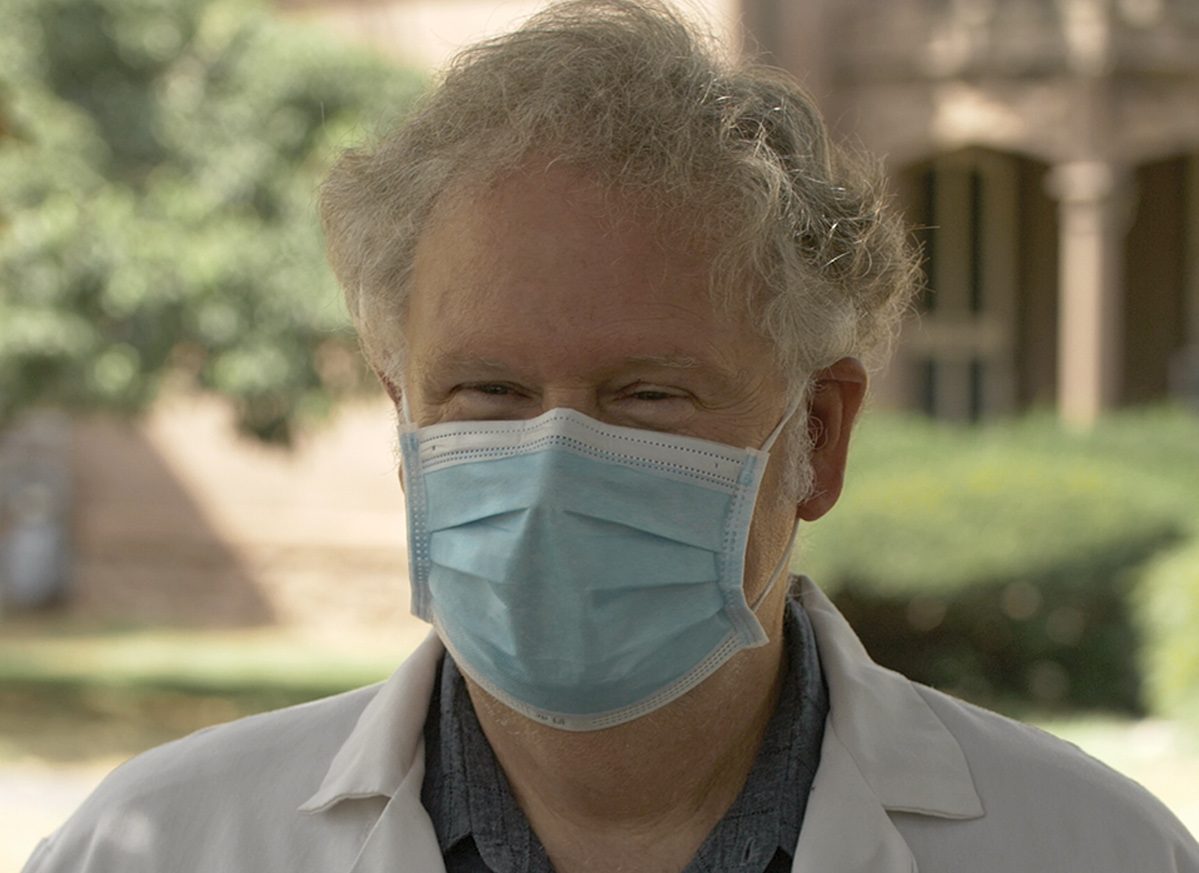

Man of His Word

After just over a year as Wesleyan’s new vice president and dean of admission and financial aid, Amin Abdul-Malik Gonzalez ’96 reflects on the institution that opened him up to new perspectives and discusses the importance of accountability and authenticity in shaping a new class of critical thinkers.

Amin Abdul-Malik Gonzalez ’96 wants to set the record straight.

He’s relaying an incident from the early years of his admission career. One in which a writer, embedded as a fellow admission officer, wrote a book portraying Gonzalez as being brought to tears over a candidate who was ultimately not admitted to the incoming class. As Gonzalez remembers it, “The committee discussion was intense. I was passionate about the outcome and I was certainly invested, but I was not crying. The author took creative liberty with that characterization. I stand by the things I say and the sentiments behind them, but I don’t appreciate having added emotions or words that are not true attributed to me.”

He offers up this anecdote not to defend against a perceived slight or to dispute the intensity of his feelings at the time, but rather to illustrate one of the many formative episodes in his life that have reinforced the importance of words and context, perception vs. lived experience.

In talking to Gonzalez, one gets the sense that he is a clear-eyed and practical thinker who is careful about how he expresses himself and who prizes clarity of meaning and authenticity in his communications. His responses feel thoughtful and well-considered, laden with purpose, intentionality, and empathy—particularly for those who have historically been overlooked and underrepresented.

From Recruit to Recruiter

Gonzalez’s own story is one with its share of difficulties. Born in Hell’s Kitchen, raised in Spanish Harlem in the midst of the crack epidemic, and orphaned by age 13, he was able to attend Loomis Chaffee School in Windsor, Connecticut, through the support of the Oliver Scholars Program. At Loomis Chaffee he discovered a talent for the sport of wrestling and through his coach, heard about Wesleyan.

“Wes was more diverse by far than many of the other liberal arts colleges at the time. It had a progressive, inclusive environment and a clear commitment to students of color. It was a natural place for me to apply,” he explained.

He was recruited to wrestle for Wesleyan, but soon found that academic commitments and financial responsibilities had to take precedence. Despite his love of sports, the decision was a practical one, rooted in the reality of what he needed to do to succeed as an independent first-generation low-income college student and as an adult in the life he envisioned beyond graduation.

“I backed away from athletics in favor of becoming more of a scholar out of necessity. I knew my future would not be in athletics; I was not going to go pro or do anything significant enough in the athletic realm to support a family. So, I focused on my studies and put myself wholeheartedly into that,” Gonzalez remembers. “My first year was challenging. I was finding my feet, making some choices and learning the ropes of financial independence. I worked a lot of hours and spent a good deal of time trying to manage this new college environment.”

Gonzalez would go on to earn a Mellon Minority Undergraduate Fellowship (now known as the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship) and would spend a semester in Egypt, studying Arabic and doing a deeper dive into theology as part of a spiritual journey that would eventually become an important touchstone in his personal and professional identity.

Krishna Winston, the Taft Professor of German Language and Literature, Emerita, met Gonzalez during his sophomore year when he applied to the Mellon Program, which she coordinated. She remembers him as a serious and compassionate student, driven to learn more about the world and to use his experiences to help others. “As an undergraduate Amin impressed me with his maturity and his marked sense of responsibility,” she recalls. “Already serious about converting to Islam, he worked hard to learn Arabic at a time when Wesleyan didn’t yet have a full-time instructor in that language. A full-time student, he nonetheless served as a surrogate parent to his younger siblings. Deflected from a PhD (through no fault of his own) but still a passionate advocate for higher education, Amin found his calling in admission work. In that profession, he affects the lives of so many, and does so with intelligence, insight, integrity, and compassion. We are so lucky to have him!”

The Benefits of Diversity for All

Nearly three decades since he first set foot on campus and following an extensive search process, Gonzalez returned to Wesleyan as the new vice president and dean of admission and financial aid in August 2019.

Despite being a Wesleyan alumnus, Gonzalez admits he was not necessarily an obvious candidate to eventually build the next generation of Wesleyan students: “I was never a tour guide. I was never a senior interviewer. I was a dedicated alum, certainly, but I wasn’t an overly eager ‘Wes or bust’ ambassador. My presentations of Wes have always been honest and shared through my individual lens.”

Despite being a Wesleyan alumnus, Gonzalez admits he was not necessarily an obvious candidate to eventually build the next generation of Wesleyan students: “I was never a tour guide. I was never a senior interviewer. I was a dedicated alum, certainly, but I wasn’t an overly eager ‘Wes or bust’ ambassador. My presentations of Wes have always been honest and shared through my individual lens.”

Ironically, part of that reasonable skepticism is what made him an ideal choice. “My goal was and is to push the institution, to continue to be a voice for the disenfranchised, the underrepresented, and to present the power of these perspectives,” he explains. “I’m not selling cars. If I don’t agree with policy, I’m not going to misrepresent reality. My job is to be authentic, and balanced. I can be constructively critical of the University, but also be authentically enthusiastic about the education and the experience it offers. My alum background helps because it lends credibility and connects me to people and programs on campus. Wes is familiar enough that I was comfortable returning after a long hiatus, but also different enough now that I can’t be complacent.”

Delivering on the Wesleyan Promise

One area that Gonzalez would like to push is changing the conversation around “diversity” and addressing the misperception that it and excellence are mutually exclusive.

“It’s not just the first-gen low-income students that I’m invested in. I’m invested in the white students who are affluent, and what their experiences are by virtue of being around low-income students. Diversity is not just about increasing access for underrepresented populations in a way that only benefits them; their presence and full engagement benefits everyone. And we need to reframe that conversation, to be more about what we’re gaining rather than what we are giving up, without being exploitive of individuals asked to represent experiences that are not monolithic. We are significantly more enriched by the presence of these students who bring with them a multitude of backgrounds, perspectives, and talents,” he says. “Learning to lead, engage difference, and make meaningful connections across cultures will help our students in whatever fields they pursue beyond Wes.”

A living example of success being equal parts effort and opportunity, Gonzalez hasn’t forgotten the experiences that brought him here—the challenges, the work and commitment needed to overcome them, and the individuals and organizations that reached out along the way. He is determined that Wesleyan remain a place where students of all stripes have the access and support to achieve their goals.

Increasing access, aligning the admission process with the priorities of the University, and reinforcing the values exemplified in a Wesleyan education are just some of the challenges that Gonzalez has set his sights on—not to mention doing this while also dealing with the continued fallout and reduced enrollments as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. But ultimately Gonzalez measures success in simple terms and with each new class of future graduates:

“We want to be accessible to students of all backgrounds: political, geographical, religious. We want to be who we say we are, to deliver on that promise. A real hallmark of the Wes education is to be a place where everyone has the potential to thrive, whether they see themselves fully represented in the environment or not, and beyond demographics. We are teaching students that their voices are valued, even if they are in a minority of number, and that they can effect change, regardless of where they hail from.”

Photos by Robert Adam Mayer