Lights Up on the Future of Filmmaking

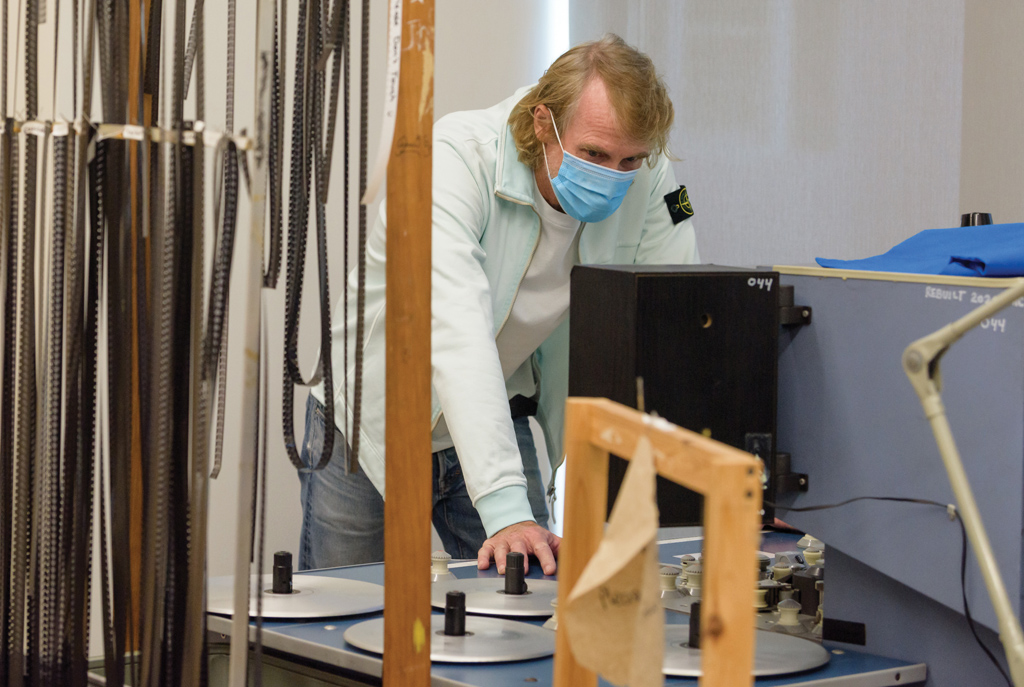

Photo by Olivia Drake MALS’08

The College of Film and the Moving Image looks toward the future of the art form, led by the new Wesleyan Documentary Project

By Steve Scarpa

In the gleaming new Jeanine Basinger Center for Film Studies, replete with new classrooms, auditoriums, and production spaces, a healthy appreciation for film history informs the latest in creative thinking. Wesleyan University’s already robust film legacy is poised to grow further with the creation of the new Wesleyan Documentary Project.

Former director Jeanine Basinger (for whom the new center was named) was instrumental in building the program from the ground up and establishing its focus on movie theory and its thriving network of alumni in film.

“We have inherited such a strong foundation. The only way we could go wrong is to let it erode and fail to grow it. So, what I think we need to do is to use what we’ve been gifted with, which is a tremendous alumni network and a terrific faculty that works so well together,” said Scott Higgins, who is the director of the College of Film and the Moving Image.

Interest in film on campus has never been stronger. There are approximately 150 students majoring in the program and another 50 or so with a film minor. This doesn’t count the many students who engage with the art form through film clubs and other extracurricular activities.

“We teach popular cinema as a relationship between the film, the filmmaker, and the audience, but it’s not a relationship you need to overcomplicate. Most of teaching film at the undergraduate level is about getting students to recognize how much they already know and to become aware of how a movie or piece of art makes them feel,” Higgins said. “We are saying it is ok to feel.”

A crucial part of that future rests with the new Wesleyan Documentary Project, co-directed by Tracy Heather Strain, the Corwin-Fuller Professor of Film Studies and associate director of the College of Film and the Moving Image, and Randall MacLowry ’86, the founders of The Film Posse. The pair brings an impressive pedigree to the University. Strain has won two Peabody Awards; MacLowry has won a Peabody and two Writers Guild of America Awards.

Back in the 1990s, when Strain was getting started, documentaries were a “nerdy” backwater of the film industry, she said. A few major pieces, like Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line, gained public traction, but it was not a genre where blockbusters could be found. She recalled attending a film market where people couldn’t understand why anyone would spend money to promote a documentary.

Strain believes times have changed. Streaming services have an unceasing need for content. The technology to make films has become democratized —most cell phones take very credible video. People are also becoming more comfortable with nonfictional and personal storytelling.

Because of all these factors, both she and Higgins said student interest in the genre is booming. “There is a groundswell and we are able to support that,” Higgins said.

“I feel like the students who have self-selected to take documentary courses are really motivated and interested in engaging with the material. Most of them are surprised about how varied the art form of documentaries can be. When they first come in they have certain ideas and after they leave, their minds are kind of blown in some ways,” Strain said.

Documentary filmmaking is very much in line with Wesleyan’s interdisciplinary approach to education. “There’s great value in studying and majoring in other things than just film,” Strain said. “We make films about people, places and things —the human condition.”

The Documentary Project is in its initial stages, but Strain is already looking toward the future. She anticipates holding a biennial documentary conference at the Jeanine Basinger Center for Film Studies. She hopes to connect alumni more formally with current students to provide internship and career opportunities. Alumni have already supported funds to help first generation students and students of color on their senior thesis films and to help facilitate access to professional opportunities.

Faculty will also reassess the entire film curriculum, putting issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion in the forefront of their thinking, she said. “We want to think about how film has played a role in how people in the world actually perceive differences. Film is a big part of the stereotyping in our world,” Strain said.

According to Strain, CFILM is entering a new phase, one that is welcoming, becoming more diverse, and is forward thinking.

Contrary to the public perception that Wesleyan churns out a “Hollywood Mafia,” Higgins said that they do not consider the film program to be a trade school. The department is interested in exploring the history of the art form—all the byways that film took over the course of its evolution. By knowing the form intimately, Higgins believes that students are best positioned to be creative and inventive in their own work. He noted the work of two other new professors—Anuja Jain, a South Asian film expert, and Sadia Quraeshi Shepard, a documentarian and expert on film adaptation—as widening the department’s focus overall.

“Making a film is not an escape from history. It’s not an escape from film analysis. Our job is to combine history and theory and to keep them balanced. I think our job should be to make every film history class into a secret filmmaking class and make every filmmaking class into a secret history class,” Higgins said.

By melding the two disciplines—practical work with delving into film history, there is a singular outcome. “It’s about storytelling,” Strain said.