Reframing the Presidents

Special Collections & Archives takes a fresh look at the tenures of Wesleyan’s past presidents and reveals the ups and downs of their legacies—misguided decisions, progressive ideals, tenuous relationships with the student body, and more.

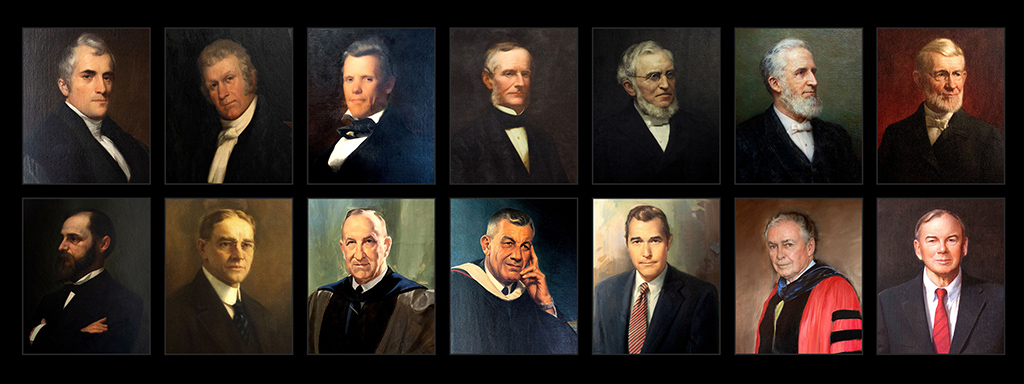

Olin, Foss, Fisk, Shanklin . . . their names have become part of the lexicon of the University. But before they were names on a campus map, they were presidents. Ministers, academics, businessmen, and administrators charged with leading a burgeoning university through nearly two centuries of history.

Their portraits have hung around Olin Library for as long as most alumni can remember, greeting patrons with the stoic visages of days past. But to today’s students, these portraits have little meaning, and the presidents’ part in shaping the University we know today is largely forgotten.

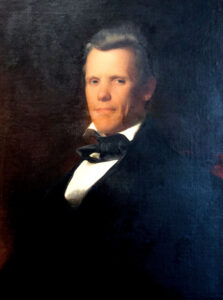

That rather severe-looking individual with the stern look and the white curl in the middle of his forehead? That’s Willbur Fisk, Wesleyan’s first president. A man who helped foster a culture of social responsibility, equity among the faculty, and a civic-minded community. From his first speech he preached progressive education reform. But as much as Fisk has been lauded for his morality and encouragement of social responsibility, he was less than progressive on issues of slavery and admitting non-male students to Wesleyan. And despite enrolling the first Black student, Charles B. Ray, during his term, when Ray was harassed and forced to leave campus, Fisk did little to protect him.

In contrast, Wesleyan’s popular third president, Stephen Olin (1842–1851), saw the divide between pro-slavery and abolitionist groups in the Methodist church as a threat to the unity and harmony he craved. A former pastor turned professor, Olin tried to serve as an intermediary between the two groups, intervening (unsuccessfully) in hopes of brokering a compromise.

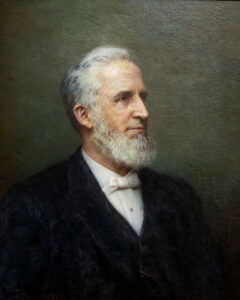

And while Cyrus Foss (1875–1880) was well-liked and oversaw a period of growth and prosperity on campus, including endorsing the enrollment of women and welcoming the input of the faculty and the board, William A. Shanklin (1909–1924) was a much more polarizing and controversial appointment. A strong fundraiser who led multiple endowment campaigns, Shanklin was often absent from campus (on fundraising trips but also to serve for six months in France during World War I) and his relationship with the faculty and board continued to deteriorate throughout his tenure.

This more tempered look at the presidential legacies was part of the library’s larger commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, which began in summer 2020. “The library wanted to have more spaces for students to showcase their work and art,” said University Archivist Amanda Nelson, “which was difficult with the portraits of the presidents hung throughout the library with no contextual information.”

In the summer of 2022, the official presidential portraits—14 total, with 1 (William Chace) still in process and another (Michael Roth) yet to be commissioned—were moved to the second floor of Olin and rehung in chronological order. In addition, Nelson and student researcher Lily Spar ’23 used the opportunity to create a presidential gallery with new biographies to contextualize each portrait. The short biographies use a modern lens to present a more balanced look at each president’s legacy, including misguided decisions, great leaps forward, troubled relationships with students and faculty, and much more.

“One thing we discuss in all the classes that visit Special Collections & Archives is the importance of context. Within the library world, there’s been a shift to make descriptions of collections as unbiased as possible and to understand the inherent bias we have. These portraits shouldn’t be any different. Previously biographies of influential figures would have only highlighted the positive, but it’s important for the students to see these men as actual people with both successes and flaws,” Nelson explained. “By adding these biographies next to the portraits and arranging them in chronological order we allow the students to see the progression of how Wesleyan has changed and how the presidents are a major part of those changes.”

Take, for example, the rather pensive-looking fellow depicted in academic robes with a finger at his temple. This is the official portrait of Victor Butterfield, who served as president from 1943 to 1967—the longest tenure in the school’s history—and one of Wesleyan’s most beloved leaders. In his twenties, Butterfield hitchhiked around the United States and worked on farms. These early experiences helped shape his leadership and contributed to his belief in student discovery and academic freedom. It was under Butterfield that the College of Social Studies and College of Letters came to be.

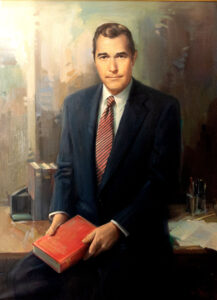

By contrast, Butterfield’s successor, Edwin Etherington (shown in his official portrait in a dapper business suit that would be equally at home on Madison Avenue as on High Street), held one of the shortest terms (1967–1970), during which he oversaw a period of heightened social justice efforts and student protest. An alumnus of Wesleyan, Etherington had been elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and was part of the Eclectic Society, Skull and Serpent, and The Argus. And while Etherington was instrumental in reinstating coeducation on campus and increasing the number of students of color enrolled, he left his position rather abruptly for a failed bid as a Republican candidate for the United States Senate.

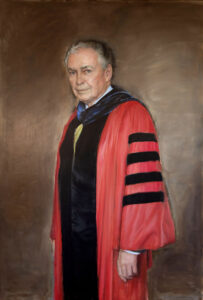

Taking over for Etherington was Wesleyan’s youngest president at the time, Colin Campbell (1970–1988), shown as an arresting figure in bright red academic robes. Through difficult financial and political times, Campbell presided over one of the most volatile periods in the University’s history. Still, he continued to maintain a close relationship with the student body and was well-liked for his candor and optimism (despite calling the police on student and alumni protestors during a 1985 demonstration).

For Spar, the most enlightening part of her research into the presidents was seeing how each one’s relationship with the students impacted his term. “Thinking about the early Methodist roots of the University and the continued paternalism to the transition away from in loco parentis, each of the presidents approached communicating with the student body very differently,” she said. “I found that the ‘best’ presidents, the ones beloved by students, faculty, administrators, and alumni, were the ones who made the best effort to know the students as they were, individually and communally.”

Biographical research provided by Lily Spar ’23