From the Collections: African Material Cultures and the Archaeology & Anthropology Collections

Stories and legends abound regarding the Orange Judd Museum of Natural History, the teaching museum that existed on Wesleyan’s campus between 1871 and 1957—the giant ground sloth skeleton whose unwieldy pelvis mysteriously disappeared on campus and has never been found; the bizarre subscription we purchased in the 1920s from the American School of Prehistoric Research, which bought us the occasional box of Paleolithic stone tools in the mail; the legendary “Wesleyan Mummy,” brought to Middletown by a Wesleyan professor in 1884; and the several years that the museum’s collection spent in the dark and humid tunnels under Foss Hill. The museum is gone, but the cultural objects within now comprise the Archaeology & Anthropology Collections (AAC), an assemblage of more than 30,000 archaeological and ethnographic objects from around the world used for teaching and research. During the 2022–2023 academic year, six student researchers and interns narrowed their focus on one of the least-understood aspects of the museum’s legacy—the African collections.

In the Venn diagram of history, where do a small, 19th-century museum in Middletown and the continent of Africa meet? According to our students’ research, in more places than you might think. The museum collection originated in tandem with a campus missionary organization called the Missionary Lyceum. Established in 1834, the Missionary Lyceum was intent upon “awakening Christian sympathy and calling forth benevolent action” around the world, in part by building a Mission museum or “cabinet” in Middletown. Two weeks after the establishment of the organization, corresponding secretary Reverend Daniel P. Kidder began an aggressive letter-writing campaign to encourage missionaries around the globe to collect objects from their mission communities for this purpose. In a letter to Reverend Spaulding (stationed in Africa), Kidder requested that he donate his collection to the cause, and states, “It was supposed and is still believed that missionaries in distant lands would feel a peculiar interest in the establishment of such a museum; where articles of their own collection will remain to be examined by their friends and in future times be treasured as relics of their labors and of their love to man.”

Kidder’s appeal to missionary egos must have been persuasive because, according to our catalog records, they delivered. By 1870, the Missionary Lyceum (now with dwindling membership and diminishing zeal) had gifted an enormous assemblage of objects to Wesleyan University. Spectacular in its beauty, remarkable in its diversity, and fraught in its origins, it included feather headdresses from Brazil, beaded moccasins from the northern United States, carved wooden weaponry from Oceania, and woven textiles from Ecuador. Significantly, it also included a substantial collection of objects from Liberia, a US colony founded by the American Colonization Society.

The Liberian objects were collected by Reverend John Seys during the first half of the 1800s, and they lie at the center of the recently launched African Material Cultures @Wes Initiative, a collaboration between the AAC and African Studies. The primary goal of the project is to make African collections (donated by the Missionary Lyceum and others) more visible and accessible. But with students’ help, we are also coming to understand Wesleyan’s connections to Africa during the 19th century, the material culture of the new nation of Liberia during a period of rapid political change, and how museum collecting was situated in colonial practice and rhetoric. Here we highlight a few of the objects that sparked the interest of our student interns over the last two semesters, leading to their fascinating research and many thoughtful team discussions.

Snuff Grinder

This carved wooden object was used much like a mortar and pestle, but was designed specifically for grinding “smokeless” tobacco. The taking of pulverized tobacco through either chewing or sniffing is believed to have originated in the Americas before spreading to Europe, and was introduced to Africa by French colonists by the 16th century. This snuff grinder was collected by Reverend Seys in Monrovia, Liberia, some time prior to 1850. Current research around this object is focusing on how tobacco was situated in West African political, social, and spiritual life during the 19th century, and its role in Liberian material culture.

Blacksmith Bellows

This object came to Wesleyan via Frederick Northam, a donor who attributed his entire donation to “Western Equatorial Africa” in 1872. We know very little about Northam, his relationship to Wesleyan, or his reasons for traveling to Africa. But these pot or bowl bellows are illustrative of the rich tradition of metallurgy in Africa. The air-pipe and bowls are carved from a single piece of wood. Note the two holes at the distal end of the air-pipe, and the animal hide diaphragms covering the pots (secured with plant fiber cordage). When in use, two sticks or handles would have been inserted in holes in the center of the hide covers and moved up and down to pump air through the air-pipe and out through the two small holes toward the fire in the furnace. This constant pumping (likely in concert with several other bowl bellows arranged around the furnace) would have injected a constant supply of oxygen into the fire. The bellows were crucial to keeping the fire hot enough for metalworking. Our students’ research so far suggests that, based on the style of the bellows, this object likely originated in Cameroon.

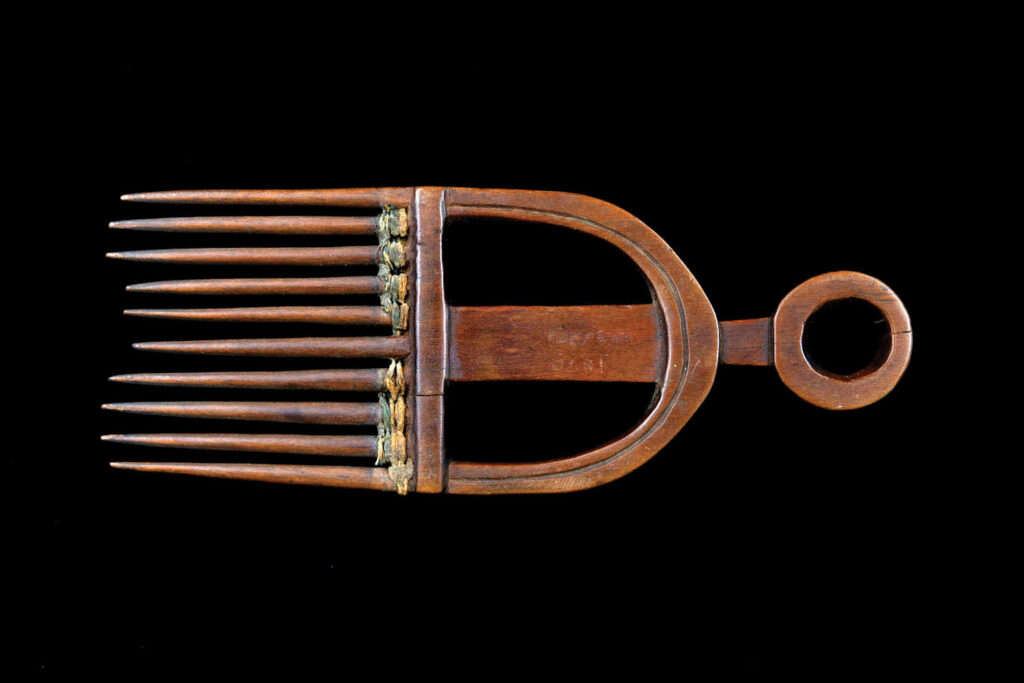

Other objects originating in Africa include a hair comb, a set of painted cups or bowls, coils of rope, pipes, metal swords and knives, and carved wooden spoons. Our team will continue to research these objects over the course of the 2023–2024 academic year so that we can better integrate them into Wesleyan’s curriculum. This work will evolve in ways that align with the interests and concerns of our faculty and students, namely around the ethics of museum stewardship and connecting with descendant communities. Viewing of the African collections can be arranged by contacting the archaeology collections manager (wmurray01@wesleyan.edu). Many thanks to Associate Professor of History Laura Ann Twagira and the African Studies faculty, as well as Idenya Bala-Mehta ’25, Sarah Brown ’23, Josie Dickman ’26, Emma Kendall ’24, Adam Mohn ’26, and Julia Noriega ’24 for their efforts in this project.

Wendi Field Murray, Archaeology Collections Manager/Repatriation Coordinator