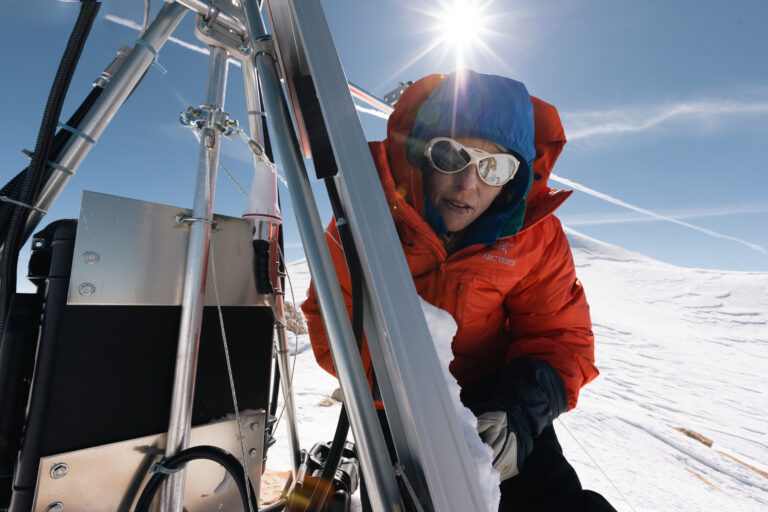

Ice Breaker: Alison Criscitiello ’03

Glaciologist and climate scientist Alison Criscitiello ’03 scales the world’s tallest mountains, pushing the limits in pursuit of high-risk, high-reward impactful science.

Alison Criscitiello’s body was slowly deteriorating as she made a temporary home—and office—out of Mount Logan’s summit plateau for two weeks in 2022. On the second-highest peak in North America, she led a team of six scientists, surviving at nearly 20,000 feet above sea level, atop some of the oldest non-polar ice on the planet, through winds that could whip up to 80-miles-per-hour and beyond, with nothing but the nylon of their tents and their thickest winter gear to guard against the sub-zero temperatures.

Everything is harder with less oxygen coursing through the bloodstream, not to mention the brutal elements. Sleeping, eating, hydrating, walking . . . breathing. But Criscitiello, a 2003 Wesleyan graduate, National Geographic Explorer, and the director of the University of Alberta’s Canadian Ice Core Lab, wasn’t just trying to exist on Mount Logan. She was on a mission, as part of the National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Expeditions program, to extract a 2,000-pound ice core from one of only a handful of places outside of the polar regions where it doesn’t melt in the summer. The lack of thaw means the glacier holds a well-preserved climate record, which could allow the past to inform our environmental future. For 14 hours a day, she and the team worked in shifts drilling 1,073 feet down into the ground, in the hope that their work would reveal a treasure of 30,000 years worth of data in the form of gas, pollen, isotopes, and dust.

“There are a number of reasons why a long-term climate record from the North Pacific is very important. For example, to get a better handle on temperature change in the past,” Criscitiello says. “We’re also measuring a bunch of wildfire markers so we can reconstruct not only the wildfire frequency in the past, but also the vegetation that was burning. That’s important in the Northwest, where people care a lot about the future projections of wildfire frequency.”

But first, the team had to get there. From the base camp at 10,000 feet, they scaled the King’s Trench mountaineering route through Canada’s Yukon territory, over nine days. Pulling gear and equipment on sleds, they split the climb into segments, completing each segment twice so that they could gradually acclimatize to the altitude. “You take half your load up, drop it, ski down, sleep low, then take the rest and move up, over and over,” Criscitiello says. “We started as seven people and ended as four because of altitude-related, serious illness.”

It takes a special kind of person—part chemist, part geologist, part athlete, part mountaineer, part dreamer—to do the work that Criscitiello does. As you might have guessed by now, everything about her career is extreme and few people have that unique combination of curiosity, intellect, and ability to pursue such exploits in the name of science. For Criscitiello, 42, it all started while growing up in the Boston suburbs, where she tended to get lost in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, with her twin sister. They’d head to the Presidential Traverse Trail and see where the wind blew them—sometimes literally. “We had no idea what we were doing,” Criscitiello says. “You can get into trouble even though most people think there aren’t very big mountains there. They’re big enough, especially as a kid.”

Nonetheless, the free-range childhood seeded an intrigue with all-things winter, snow, exploration, and the outdoors. When Criscitiello landed at Wesleyan, those passions melded with a growing interest in science, though she was initially attracted to the campus not because of any particular program, but by its “very diverse group of free thinkers,” she says. “It was the perfect fit. I walked away with something that has served me every single day: how to think.”

What Criscitiello probably didn’t fathom when she graduated with a BA in earth and environmental sciences, however, was that she’d become a trailblazer in every sense of the word, though you’d be hard-pressed to hear any of it straight from her (she shies away from discussing the details, like the fact that she earned the first-ever PhD in glaciology conferred by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology). She led the first all-female ascent of Lingsarmo, almost 23,000 feet above sea level in the Indian Himalaya. She’s traversed the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan on skis and studied the uninhabited Axel Heiberg Island in the Arctic Ocean. In 2021, while scouting the ideal ice-drilling location on Mount Logan with her colleague Rebecca Haspel, the duo installed the highest weather station in North America.

Along the way, it’s been evident that the higher Criscitiello climbs, the fewer women she sees. It’s part of her life’s work to change that, she says. One way she’s helping to expose more young people to science and the outdoors is through the nonprofit organization Girls on Ice Canada, which serves girls, transgender, agender, Two Spirit, nonbinary, intersex, and genderqueer participants, with educational programs that include expeditions and research. It’s part of the effort for more people to see themselves in spaces traditionally occupied by men. “I’m Jewish and I’m queer, but I’m also white and came from a middle-class family in Boston, so I feel like a lot of things had to happen for me to end up where I am—and definitely one of them was privilege,” Criscitiello says. “When I started, there was just nobody who looked like me doing this kind of work. . . we are doing all of us a favor by having more diversity in science.”

A parent of two young daughters, Winter and Juniper, alongside her wife, Amy, Criscitiello has indeed become an important figure for up-and-coming female scientists, in particular. Bonnie Hamilton, PhD, is an ecotoxicologist whose thesis focused on microplastics and the transport of these contaminants in the Arctic. During her research, she connected with Criscitiello and together they studied a “first glance” of the microplastics found in ice cores from the Devon Ice Cap in Canada’s high Arctic. Hamilton has found Criscitiello’s perseverance inspiring. “As we face some of the most challenging scientific environmental questions of our time, having a mentor and colleague who encourages us to chase after high-risk, high-reward, impactful science is transformative,” Hamilton says.

Kira Holland, a PhD candidate who’s been under Criscitiello’s tutelage for several years, says she feels fortunate to have found somebody who’s consistently shown her how to barrel through barriers. “A lot of people, if they came up with the ideas that Ali does, they would stop, because it seems like a lot,” Holland says. “Her projects are quite large, logistically heavy, and very involved, but she finds creative ways to find funding and make these really crazy projects doable and successful.”

Those “crazy” projects clearly take more than money, however (though funding, of course, is critical). After such grueling endeavors, it takes Criscitiello several weeks to recover, emotionally and physically. She usually returns home feeling underfed and overtired, so her immediate emphasis is on refueling and sleeping to regain her strength and stamina. She even has to reacclimate to walking around without rigid ski and climbing boots on.

“I have embraced the fact that having a high level of fitness is part of my job, so I take time out of my work day to train,” she says, adding that she favors long-distance running as a convenient form of exercise in Edmonton. “I don’t really like going to gyms, so I just try to do what makes me happy on any given day, outside.”

Back on campus at the University of Alberta, Criscitiello spends much of her time in the lab, which is kept at a brisk -40 degrees Celsius. This is where the ice core samples are cut, archived, and analyzed—it can take several years before the research papers begin rolling out, though the technology is allowing her team to make progress at a faster clip than they once did. She basically works in a freezer when she’s not writing or training for another expedition, until she’s ready to head back out in the field. She’s already planning to do her next expedition in 2025, to the western, Arctic Ocean side of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, another region that has gone largely unexplored because it is so remote. This spring, she and her colleagues will head to the area for site selection recon work.

Criscitiello’s career may require an unusual amount of patience and grit, but the chance to test her limits and expand the boundaries of environmental science help keep her motivated through the intensity of the work. The opportunities to search for such consequential answers in some of the most astonishing locations in the world, among people who share her ambition—it doesn’t take Criscitiello more than a moment to contemplate how she keeps going.

“What doesn’t inspire me, really?” she says.

By Erin Strout

Read Criscitiello’s recollections from her expedition to Canada’s Müller Ice Cap: In Her Own Words.