Making the Grade: Wesleyan Exams through the Ages

Every year, between 80 to 100 classes visit Special Collections & Archives for sessions ranging from learning about early book history and getting to see some of our amazing first editions and artist books, to learning more about Wesleyan history. Through these documents, classes can experience the social mindedness of students and what it was like on campus in the past or compare how what has been taught at Wesleyan has changed over time.

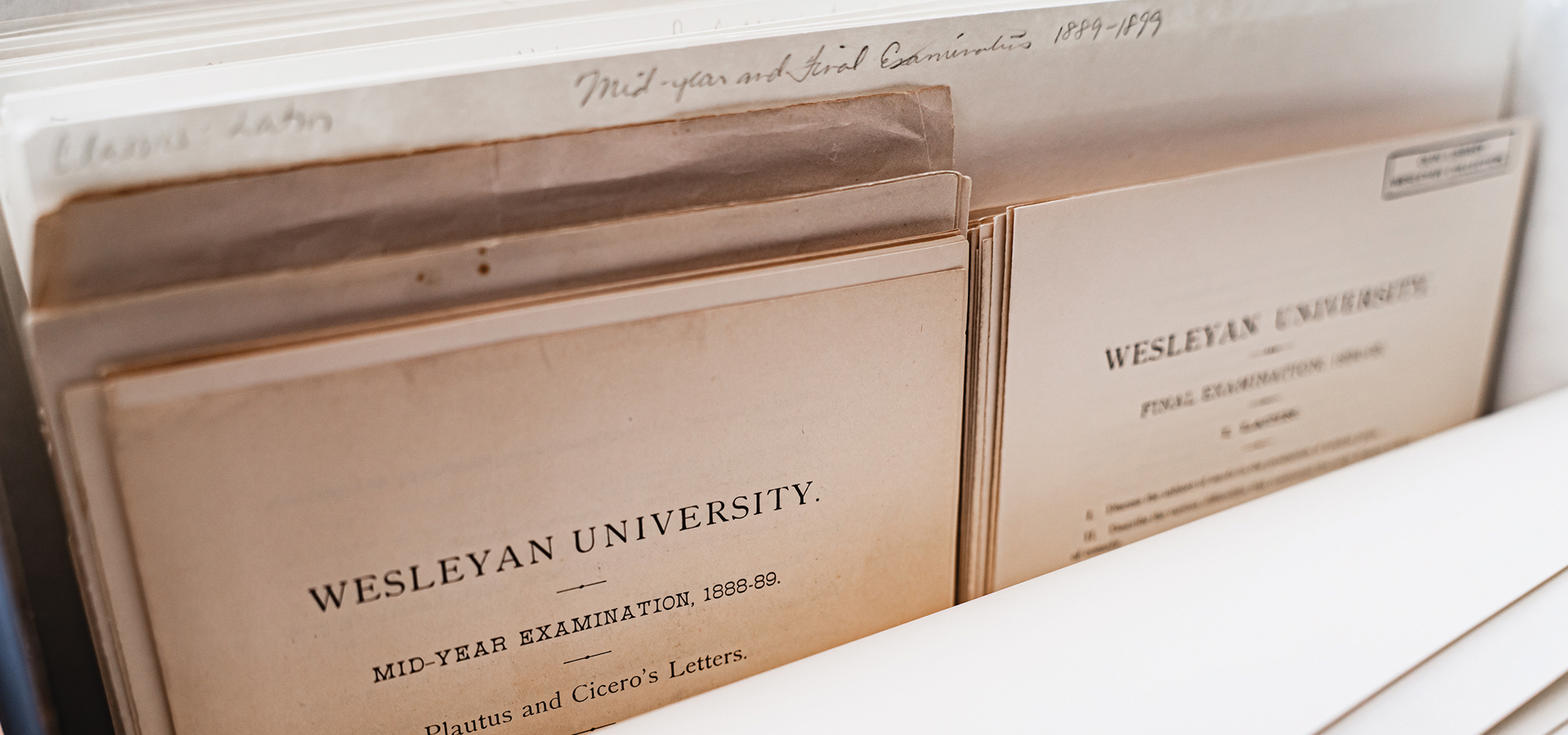

Recently multiple classes have been working with our Wesleyan University examinations collection. In the boxes and bound volumes is a treasure trove of information—and entertainment—providing a glimpse of what it was like to be a senior at Wes starting in the 1920s. At that point the idea of majors or concentrations of study was still new to the University; before majors were instituted, all Wesleyan students took the same courses as their peers all four years. Once students began to choose areas of study, Wesleyan faculty looked for ways to ensure that the students had learned what they needed to prior to graduation.

In March 1923, the University announced a new plan: Before graduation, every student would take a comprehensive exam in their course of study. This idea was laid out in further detail in the 1924–25 course catalog where it states beginning with the class of 1926, “each senior shall complete and pass a comprehensive examination over the general field covered by his major study.” The major department would arrange the nature and scope of the comprehensive examination and the amount of supervision to be given to the student.

Comprehensive exams asked students to recall information from their entire course of study. The idea of the canon—a group of academically significant works—was interspersed throughout the classes offered, and all students within a discipline took the exact same classes. Professors expected the students to have what they learned so engrained that they’d be able to write about it as seniors. Unlike today, this meant the students were not to synthesize information or give their own opinions, but to show the professors what they had retained from their lessons.

Here are examples from the comprehensive exams from the 1920s from each division. How would you do if you had learned the topic up to two years prior to seeing these questions?

- Did Chaucer have the makings of a good novelist? Use specific illustrations of plot, scene, character, setting, and humour to support your answer.

- Compare and contrast the concept of the state held by Luther, Calvin, Machiavelli, Lenin, and Neumann.

- What orbits are possible under Newton’s law of gravitation? What determines the nature of the orbit in any particular case?

As the University’s academic approach moved away from rote memorization toward more individual analysis and synthesis of ideas, these comprehensive exams fell out of favor. And with the growth of the student body in the 1970s the University expanded its course offerings, giving students a greater degree of choice for classes related to their major, similar to today. This made comprehensive exams almost impossible, leading the majors to update their graduation requirements and move to capstone projects and theses in addition to single-class midterms and finals. But a few echoes of these exams remain, especially for juniors in College of Letters (COL) and sophomores in College of Social Studies (CSS): COL and CSS students continue to have structured sets of classes that the entire group takes so faculty can test them on what they’ve learned, though the questions lean more toward synthesizing of knowledge.

Students enjoy looking at these comprehensive exams when they come to the archives as they show how much the curriculum and what was required of students has changed. They laugh and try to quiz each other from the exams most related to their class. They are also thankful that they don’t have this type of exam to graduate. But in a world of online research and artificial intelligence, it’s a joy to see them interact, question, and analyze records that they can only find in the University archives, just like the alumni before them.

AMANDA NELSON, Dietrich Family Associate University Librarian for Unique Collections & University Archivist