Can We Talk?

With global conflicts spiraling and another deeply divided election upon us, an emphasis on constructive dialogue techniques is giving students and staff members alike more effective modes of reaching meaningful understanding and empathy amid disagreement.

Race. Religion. Free speech. Even on Wesleyan’s highly engaged campus, these topics can seem too charged to touch in the current climate. Having civil conversations about controversial issues is especially challenging now, with an ongoing war in the Middle East and with a critical national election at home.

Yet, there may be no better time or place for people to learn how to engage in difficult dialogues. “For many Wesleyan folks, after they graduate, they’ll go into communities that will be more homogeneous than what we have here,” said Vice President for Student Affairs Mike Whaley. The campus “can be a challenging environment for that reason. But it also provides a lot of opportunity for folks to discuss issues, both large and small, with people who are coming from different perspectives on them.”

Last year, Whaley partnered with Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Nicole Stanton to lead an effort to tackle one of the most difficult conversations—about the Middle East conflict and campus protests. In the spring, a group of administrators, faculty, staff, and students met over several days to discuss student protest activities, including an encampment. That intense work was a key step in a broader, campus-wide endeavor to practice civil disagreement and dialogue.

During the negotiations, the group worked diligently to listen to each other’s views, with support from a trained mediator, Visiting Assistant Professor of Public Policy at the Allbritton Center for the Study of Public Life Stephan Sonnenberg.

“One of the first things that he had us do before we got into the issues and substance of the demands and the discussions and so forth, is he asked everybody in the room to really reflect on the values that we were bringing to the conversation,” Whaley said.

Those values included a deep love for Wesleyan and a shared desire to help the institution fulfill its mission. Whenever the conversation got difficult, the mediator reminded them of those values. “I found that a really useful technique when you know frustrations run high, or when we seem to be talking in circles around some things [was] to remember that everybody in the room was coming at what we were talking about from that common ground,” he said. “Once you find some common ground, it’s easier to listen for more of it and work together to discover more of it.”

Wesleyan is fertile ground for this type of engagement. “I see our students by and large as being pretty inquisitive and interested in hearing from others in the community,” said Whaley. “It’s a community with deeply held beliefs and anytime you have that, you have the associated challenge of listening, I think, intently and in a meaningful way, to people who express views that are different than your own.”

Deconstructing Dialogue

Learning to dialogue across differences was the goal behind Associate Professor of Sociology Robyn Autry’s efforts to bring two new courses to campus. In the weeks following the October 7 attack in Israel, Autry wanted to engage students in a novel way that would go beyond usual campus activities such as organizing reading groups and inviting speakers.

“I wanted to do something different,” said Autry, who is also faculty director at the Allbritton Center for the Study of Public Life. “By the end of October there were a lot of student protests spreading on different campuses across the country and people were struggling to talk to each other—here, too.”

Autry researched programs at other campuses and settled on the Intercollegiate Civil Disagreement Partnership (ICDP), a consortium of five U.S. colleges and universities, including Harvard. To promote dialogue, the partner institutions offer a fellowship program that helps students develop skills “to facilitate conversations across political difference; and create spaces for civil disagreement to flourish on college campuses.”

To bring ICDP’s programming to Wesleyan, Autry initiated a search for a postdoctoral fellow with expertise in dialogue. As the Civil Disagreement and Dialogue Fellow, Cassie Finley is teaching two classes this fall: one for Residential Life student leaders called “Let’s Talk: Civil Disagreement and Dialogue,” and a second class for first-year students.

With the courses, Autry hopes to provide students with the knowledge and skill to engage in productive dialogue now and in their future lives off campus. “I thought that it would be useful if we worked on how to talk across some of those differences more so than finding programming that would just attract like-minded people,” Autry said. “I thought it would be good if we didn’t just stay in our little echo chambers, but what if we really tried to get ourselves to talk about things that are difficult—and without yelling or ripping each other’s faces off?”

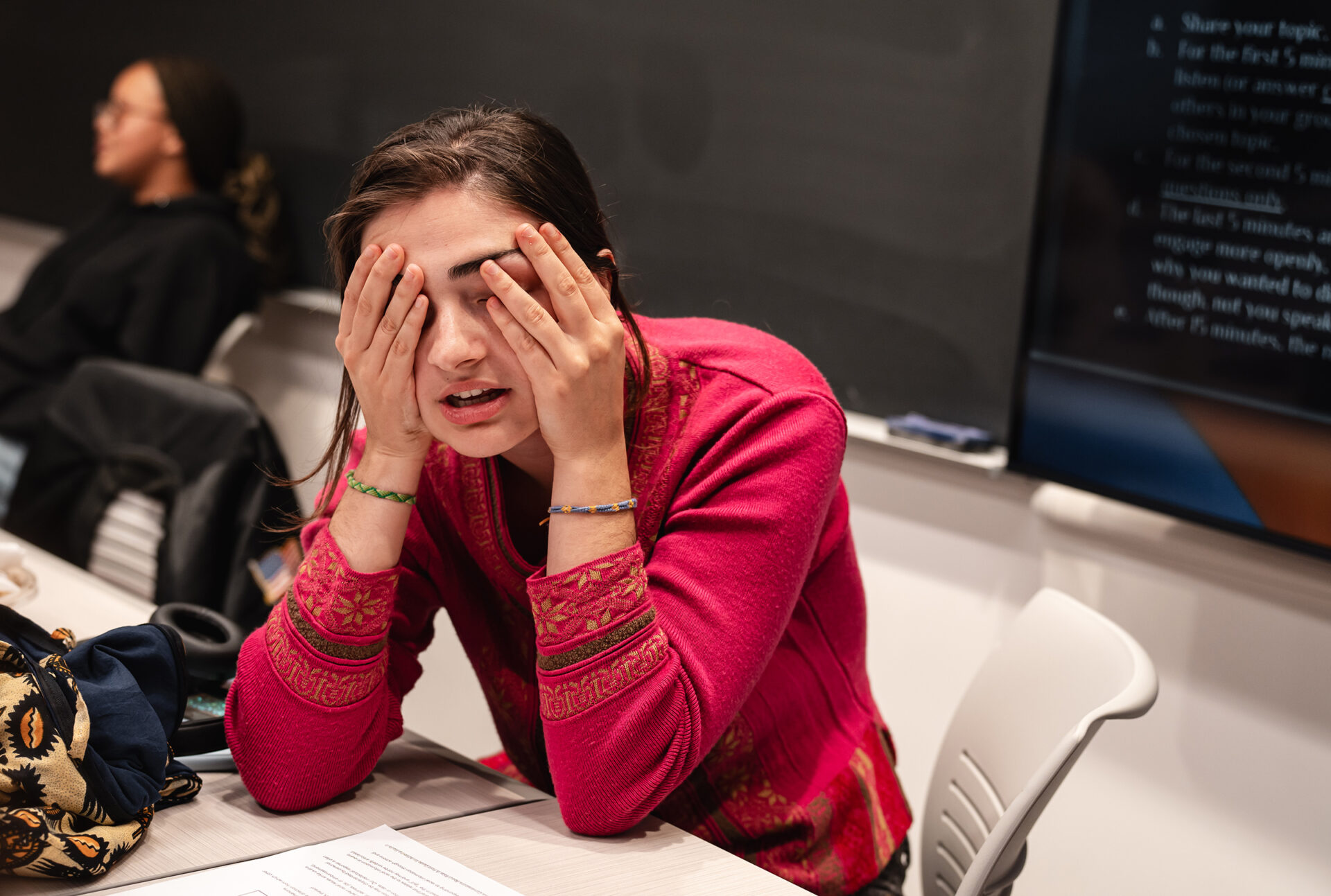

In one class, the student leaders acted out a scripted skit with a few of them playing the role of panelists in a mock debate about homelessness. In another class, they got into a heated conversation about cultural appropriation, said Sage Saling ’26, a house manager at Farm House. That discussion was the most “high stakes” one they had had, she said, because understanding of cultural appropriation differed based on where students were from, including international students.

“It was probably the most tense it’s gotten,” Saling said. But despite initial discomfort and differing opinions about the topic, the student leaders were able to engage in that discussion civilly. “It was really impressive and made me feel confident in ways to take on dialogue that maybe feels a little bit uncomfortable to begin with.”

Taking the course has also helped Saling better cope with confrontation, which can make her anxious, she said. “Those classes helped me find grounding in [the fact] that confrontation is not necessarily conflict. It’s not necessarily active disagreement. Confrontation can be misunderstanding. Confrontation is sort of a space of exploration,” she said. “Switching the way that I view confrontation has made me feel a lot more comfortable with it and has equipped me with better skills for my job and I think will serve me outside of the context of my job.”

At the end of the seven-week course, student leaders like Saling will use what they have learned with their residents, said Finley. “They’re going to be developing projects to take into their residence halls to have facilitated conversations with their residents to practice some of these facilitation skills, and also to help the other students at Wesleyan have more practice within the community of their residence halls to engage in these difficult conversations.”

Conversation and Common Ground

Vice President for Equity and Inclusion Willette Burnham-Williams sees an opportunity for Wesleyan to do more to teach listening skills that were once taught in debate classes. “I was taught you don’t listen for the argument; listen to understand. Listen for empathy. Listen for what you have in common with one another, rather than how you’re going to get to the gotcha moment,” she said.

Under Burnham-Williams’s guidance, the Office of Equity and Inclusion is working with Allbritton Center, the Office of Religious and Spiritual Life, and Academic Affairs to create more trainings for the community. “One of the things we can do at Wesleyan is create more opportunities to teach those skills. I think we have the ideal space, being who we are as the institution that was and is to teach from this pragmatic liberal institutional mindset,” she said.

“We live in a world where confrontation is just all over the place,” said student leader Saling. “I think confrontation is where discomfort can exist, and as we’ve talked about in the course, discomfort is where you learn.”