HEALTHCARE AND RACISM: A TOXIC MIX

Recasting Metabolic Syndrome

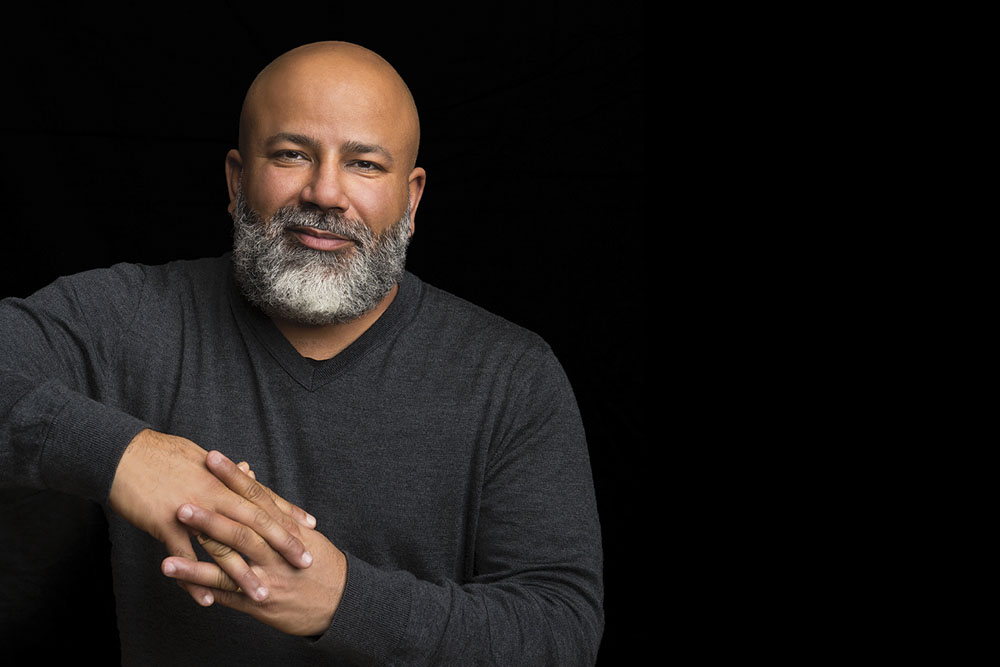

Associate Professor of Science in Society Anthony Hatch, who has been living with type 1 diabetes for more than 25 years, is in a unique position to write about metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that include elevated blood sugar. Usually prevalent in developed nations—the CDC puts the U.S. rate at nearly one in four adults—the syndrome carries an increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, amputations, and stroke, with the worst outcomes hitting black people. In his most recent book, Blood Sugar: Racial Pharmacology and Food Justice in Black America, Hatch asks his readers to shift their focus from the biology of “race” as a determinant of metabolic syndrome to the politics of racism and class inequalities.

Government agencies and researchers sort and analyze health information along racial lines. Pharmaceutical corporations recruit subjects for drug and dosage trials for metabolic syndrome based on race. Associate Professor of Science in Society Anthony Hatch considers this racial division a red herring.

“We want to know not how race structures health inequality, but how racism structures health inequality.”

Metabolic syndrome, which also includes high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obesity, is not a condition where genetic predisposition is racial, he says. “‘Race’ is not really a thing that exists in bodies. It’s a concept that exists in the social and in the cultural,” Hatch explains, noting that the concept of race emerged in the 1600s—a category socially constructed around presumed biological differences. “We can’t go into your body and find any organ that would tell us what race you are. Yet race is used as a foundational concept in biomedicine in ways that need reckoning.’

When a disease—metabolic syndrome, for instance—appears to be more prevalent in one group than another, Hatch stresses, it’s important to understand the social and environmental context in which the affected people live. Their bodies reveal the health costs associated with living in a society that does not provide equal access to resources. Like the miner’s canary, black people living in poverty are often the most vulnerable and often succumb first to unhealthful conditions that threaten us all.

The Personal is Political

In the preface to Blood Sugar, Hatch describes the self-monitoring process to treat his type 1 diabetes. The illness demands resources: daily vigilance, frequent doctor’s appointments, and funds to pay expenses associated with monitoring equipment. He estimates that test strips alone over these two-plus decades would add up to more than $70,000 retail. Ever-improving technologies provide more precisely calibrated treatments—although those without adequate health insurance may find the costs prohibitive. Hatch notes that he is fortunate: excellent health coverage, a supportive family and community, advanced education, a career offering flexibility, and access to healthful food—even training as a chef—all these factors have enabled him to enjoy a high quality of life while dealing with a chronic illness.

In the preface to Blood Sugar, Hatch describes the self-monitoring process to treat his type 1 diabetes. The illness demands resources: daily vigilance, frequent doctor’s appointments, and funds to pay expenses associated with monitoring equipment. He estimates that test strips alone over these two-plus decades would add up to more than $70,000 retail. Ever-improving technologies provide more precisely calibrated treatments—although those without adequate health insurance may find the costs prohibitive. Hatch notes that he is fortunate: excellent health coverage, a supportive family and community, advanced education, a career offering flexibility, and access to healthful food—even training as a chef—all these factors have enabled him to enjoy a high quality of life while dealing with a chronic illness.

Others aren’t so fortunate. One morning on a commuter train in Baltimore, Hatch watched a young black man eat two chocolate glazed doughnuts and drink a 20-ounce container of Sunkist orange soda. “Why was my brother eating this poison for breakfast? Why is it even possible for him to buy this food?” Hatch had asked himself. “While I had lingering suspicions at the time that this idea of metabolic syndrome was problematic in ways I had yet to discover, . . . I believed that this young man and so many of the world’s oppressed people were being killed on an installment plan for nothing less than profit, privilege, and power.”

Privilege and power are the subtext to the book’s title, Blood Sugar, in yet another way: the history of sugar. In Caribbean fields enslaved Africans and indigenous groups were forced to cut cane under awful conditions. The sugar was literally paid for in blood.

When asked about the juxtaposition that begins his book—the costs of disease and the prevalence of junk food—Hatch answers with an observation about corporate America.

“Monsanto, the world’s largest seed corporation as well as a massive food, petrochemicals, and agrochemicals corporation, and Bayer, the pharmaceutical company, are merging. In the global economy, food and pharmaceuticals are increasingly linked.

“It’s not lost on these companies that their commodities are part of a cycle: When you consume a sugary food, your body produces an effect,” he explains. A sharp spike in blood sugar follows a breakfast of two doughnuts and a large soda. Continue to do that and eventually your body may respond with weight gain, increased blood pressure, and insulin resistance, setting the stage for type 2 diabetes—metabolic syndrome, in other words. For that, pharmaceutical companies create products that will mitigate those symptoms—which people (and insurance companies) will pay for, thus generating a secondary profit from the initial cost of the high-sugar, high-fat, highly processed food that was bought, perhaps, at a nearby convenience store. Grocery stores that offer fresh fruits and vegetables, as well as high-quality meats and proteins, are scarce in low-income areas with high minority populations.

While choices are a necessary and even desirable part of what Hatch calls “a supposedly free, capitalistic society”—in that we are free to buy the food we want, free to make our own healthful or unhealthful choices for our body, and grocery stores are free to select the neighborhoods they believe will provide them with the highest profit—he remains “vexed” by companies and health care organizations that are supposed to raise health standards, but actually don’t. “That recent merger is an exemplar of a pernicious social problem,” he says, “which links the health system to other systems that create illness.” Institutions focused on healing are often complicated and compromised in ways that aren’t good for us.

The pharmaceutical industry is one such system: “We all laugh at the drug ads on TV, with their long list of adverse side effects that could occur. But it’s remarkable how the very medicines that are supposed to help us have such great potential to do harm.” He notes that his colleague, sociologist Donald Light, among others, has documented adverse reactions to drugs as the fourth leading cause of death in the United States.

Some of these can’t be predicted—accidental overdoses, unexpected reactions and interactions—but virtually all drugs have side effects, from ibuprofen to antipsychotic medications.

The regulatory system stands, problematically, between us and adverse health consequences from drugs. While the Food and Drug Administration was established to protect us from unhealthful products, it has also been tasked with facilitating economic growth through the development of new products. The dual responsibility of government agencies—not only to protect us from untested products, but also to pave the way toward the release of new products—doesn’t work in the best interests of public health, Hatch contends, and “to fix this problem, you have to change the regulatory bloc.”

The pharmaceutical industry has been involved in funding medical research and officially defining medical problems that require pharmaceutical solutions. With 90 percent of the global market for prescription drugs located in the United States, Japan, and Europe, the companies that produce drugs are eager to provide ones that will alleviate illnesses endemic in these regions. Among these is metabolic syndrome. Although it was not prevalent in cultures with indigenous lifestyles, it is becoming increasingly apparent among so-called developing nations that are exposed to Western industrialized diets.

“Our bodies are material fleshy things that are real. But we have ideas about our body—some of which are scientific, some are economic—and they get mapped onto the body and they come and go like the tides.”

Hysteria, for example, was once a medical diagnosis given to describe women’s psychological and emotional responses to strict patriarchal social mores and expectations. Just as women in previous generations displayed those physical symptoms, Hatch suggests that the stress of living in a socially and economically unequal society might be contributing to the bodily responses that we now name “metabolic syndrome.” The symptoms of “hysteria” disappeared with changes in society—not any changes in women’s biology. So, perhaps, might “metabolic syndrome” disappear with changes in society that make environments more hospitable and less stressful, offering healthful choices as the easily available options.

“That’s one of the organizing principles of Blood Sugar. We take a problem like metabolic syndrome that is, maybe, a product of social factors. But if we define it as a biological problem and give it a medical name, then we can treat it as a medical condition with prescription drugs and ignore the problems inherent in the society where it originates,” he says.

A More Equal Society?

In other words, the very name we give to a problem organizes our response. We’ve also seen this, Hatch points out, in the recent opioid epidemic, considered a public health crisis. That the addiction often stems from reliance on prescription pain medications and its victims are often white and middle class has evoked a health care response.

Contrast that, he says, with the crack epidemic of the ’80s and ’90s. “The language around that made it a problem of morality, a problem of poor judgment, a failure to take responsibility for one’s life. It was a criminal justice problem, so we erected a massive security state in response.

“When we take a social problem and put it in the body—but don’t address it as a social problem, we try to address it only as a biological problem within one body—we end up with a partial solution. And this solution ultimately increases inequality in society.” Hatch cautions that we must not think that equal access to health care will solve the inequities in disease outcomes. “You cannot have—you cannot create—a healthier society without creating a more egalitarian society,” he says, and points to the socialized medical care in the United Kingdom to show that equal access alone is not equal wellness: “Despite more equal access to health care than in the U.S., the country still exhibits a social gradient in overall health, with the wealthy better off than the poor. Inequality still shapes the distribution of disease.”

The reason? “Most folks don’t go to the doctor until they are sick,” he points out. “So if you are only solving it at that point of access, it’s too late. What has caused people to become ill in the first place? If you aren’t addressing the fundamental causes of disease, you are catching the boat way downstream. You have to catch that boat upstream, where it began. We want to keep people well; we want to catch them before they get sick.”

Old Muckracking Journalism

For his part, Hatch has been seeking points upstream to improve health care. He’s been talking with some fourth-year medical students taught by a friend of his, a professor of pathology at Brown, as well as a historian of science and medicine. After assigning Blood Sugar to her class, the professor invited Hatch to be a guest lecturer. The students found the book eye-opening, Hatch reports.

“Their degree of frustration was palpable. Why are we not learning this? How did we not know about any of this?” Hatch recalls. “Medical students need to be taking courses in the structure of health care.”

He plans to continue in this vital area. “This is the challenge in the upcoming period: both dealing with the regulatory and structural issues in our society—and getting people who practice medicine to listen to people outside the profession who are concerned about health.

“I’m trying to lessen the suffering of people by pointing out problems in the way society is set up. I see myself in the tradition of old muckraking journalism.“I’m trying to reach down into the mud, pull something out, shine it up, and let us all see what’s there.”