Digging Into a Landmark of Women’s History: An Interview with Paulina Bren ’87

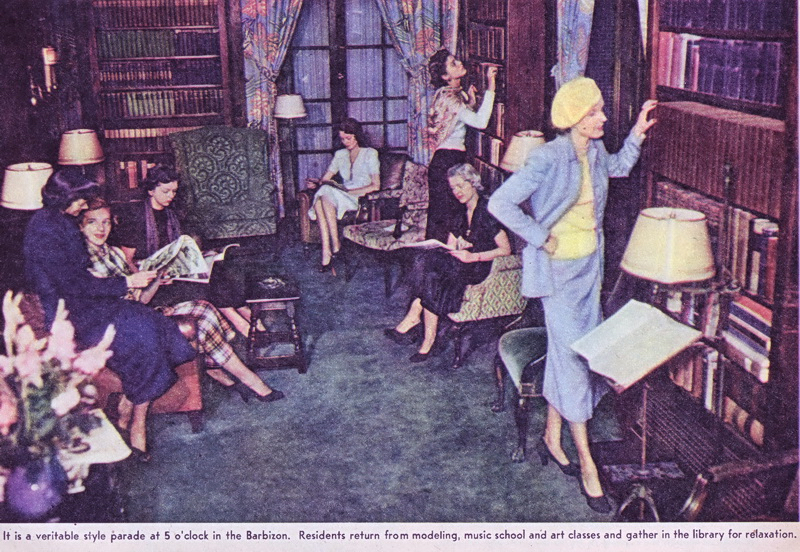

Above: Guests peruse books inside the library of The Barbizon Hotel for Women, photographed in 1950 for the New York Sunday News. A new book by Paulina Bren ’87 traces the decades-long history of the famed New York City hotel and the women who stayed there.

Fixed places and spaces don’t always receive much attention in history books, yet they are often the foundations upon which—or even vehicles through which—change and progress can occur. That’s a takeaway from The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free (Simon & Schuster), published this month by Paulina Bren ’87, a College of Letters major and now a writer, historian and professor at Vassar College. The book traces the decades-long history of New York City’s famous Barbizon Hotel for Women, which opened in 1928 and closed in 2005 (the building today exists as high-end condominiums).

Like other women’s hotels built in the early part of the 20th century, the Barbizon was open only to female guests (and primarily white, middle- to upper-class single women under the age of 30, at that). Still, its guest list includes a remarkable number of household names, many of whom stayed at the Barbizon during their formative years: the “unsinkable” Molly Brown (of Titanic fame), Joan Crawford, Grace Kelly, Liza Minnelli, Phylicia Rashad, Sylvia Plath, Janet Burroway, Gael Greene, and Joan Didion. Women’s college clubs reserved blocks of rooms for their alumni, as did well-regarded institutions such as the Katharine Gibbs Secretarial School and the Ford Modeling Agency (which was dreamed up in a Barbizon room). Mademoiselle magazine used the Barbizon as the lodging for its annual, highly competitive summer “guest editor” program for college students. As guests came in and out, the hotel evolved, too. It served as a backdrop for change in American culture, and a barometer of progress in the experience of American women in particular.

Like other women’s hotels built in the early part of the 20th century, the Barbizon was open only to female guests (and primarily white, middle- to upper-class single women under the age of 30, at that). Still, its guest list includes a remarkable number of household names, many of whom stayed at the Barbizon during their formative years: the “unsinkable” Molly Brown (of Titanic fame), Joan Crawford, Grace Kelly, Liza Minnelli, Phylicia Rashad, Sylvia Plath, Janet Burroway, Gael Greene, and Joan Didion. Women’s college clubs reserved blocks of rooms for their alumni, as did well-regarded institutions such as the Katharine Gibbs Secretarial School and the Ford Modeling Agency (which was dreamed up in a Barbizon room). Mademoiselle magazine used the Barbizon as the lodging for its annual, highly competitive summer “guest editor” program for college students. As guests came in and out, the hotel evolved, too. It served as a backdrop for change in American culture, and a barometer of progress in the experience of American women in particular.

Bren said she began to delve into research for the book in part because she had always “heard about the Barbizon . . . one associated it with glamour.” But digging into the Barbizon’s history turned up many surprises—including the fact that, for such a storied and iconic space, the hotel’s history had never been formally documented before.

Bren shared more about her writing process, her inspiration for the book, and a few lessons she learned.

What inspired this book?

Paulina Bren: I became intrigued while reading The Bell Jar, in which Sylvia Plath’s alter ego Esther Greenwood throws her entire wardrobe over the roof of [the Amazon] hotel. I was curious about that act, but also wondered what kind of hotel was this, where you could go up to the roof and throw your clothes off, down onto a New York City street? In The Bell Jar, the “Amazon” is a stand-in for the Barbizon, and in so many ways is a character in the novel. This same notion, of course, lies at the very center of my book.

You acknowledge in your Introduction that you aren’t the first person to attempt to write a history of the Barbizon, but you may be the first to complete one. What made it so challenging?

P.B.: When I started, I hadn’t realized that the sources were few and far between. I had to rebuild the Barbizon in a sense, through a whole disparate mosaic of sources that I was able to find. There was no big folder waiting for me at the New-York Historical Society Archives, even as they have an entire archive on New York hotels. There was no one place where you could go and say, “Okay, here’s the story of the Barbizon.” It took a long time to unravel, but that was also really exciting.

So, how did you conduct research?

P.B.: Finding former Barbizon guests, women now in their 80s and 90s, was a very generative moment. They told me about their time there, and in a few lucky cases, they still had letters and photographs to share.

When I discovered that Mademoiselle guest editors [had stayed at the Barbizon]—they were some of the intellectual and artistic crème de la crème of college students at the time—that was [a breakthrough]. It’s why you had people like Sylvia Plath and Janet Burroway and Joan Didion coming through the Barbizon. I found that to be a fascinating avenue of research. I also was able to access an archive in Laramie, Wyoming, which includes the working papers and memos of Betsy Talbot Blackwell, who was the formidable editor-in-chief of Mademoiselle.

Which findings from your research were most surprising to you?

P.B.: This was obviously a hotel that catered to white women. One question I had was, when did women of color start to enter that space? Nobody was able to answer the question. Then, one of these memos [from Betsy Talbot Blackwell] revealed a debate [at Mademoiselle] from 1956 about Barbara Chase, [a Black college student] whom they were considering for a guest editorship. Some people at Mademoiselle, especially the business and advertising side, were really upset by the idea of bringing in a Black guest editor. One of the reasons they were concerned was the visuals—no Black woman had yet appeared on the pages of a mainstream magazine. They also had no idea if the Barbizon would even let her in. They eventually decided to invite her, in large part due to Betsy Talbot Blackwell’s insistence. Barbara Chase in fact went on to become a famous artist and writer. I was able to meet with her, and she was just as fabulous as she was in 1956 when she arrived at the Barbizon, calling herself—and I quote her here—“the cat’s meow.”

What lessons does the Barbizon hold for us, particularly during Women’s History Month in 2021?

P.B.: I’d say two lessons. One, that women are genuinely freed if they are able to abandon caregiving responsibilities. The women who stayed at the Barbizon were able to thrive because they didn’t have to take care of anyone. They didn’t have to cook meals, they didn’t have to clean rooms. As we can see now, whenever there’s any kind of crisis, who’s quitting their jobs so they can take care of everybody?

When I look at this pandemic, looking at the numbers, right now some two million women have opted out of the workplace. We are at employment levels of 1988, in terms of how many women are in the workforce. So to me, a lesson of the Barbizon, as rarefied as it was—there’s no denying this was intended for white, middle-class, young women—is universal: If women are not burdened with always having to be the primary caregivers, they actually get the chance and the time to focus on their own ambition.

Would I want to reinstall the Barbizon? Probably not. But I do think that we need to have a conversation about the kinds of advantages a place like the Barbizon offered, because the pandemic is making it glaringly obvious that caregiving, regardless of everything else, is the question that was never sorted out through feminism and the women’s movement. Men might be helping more, but women remain the caregivers.

The other lesson is, of course, how important relationships among women are… how important it is for women to have these spaces, even if they’re not institutionalized in that sense of the Barbizon. We do mimic them, I think, even when we just go out with female friends for dinner and drinks.

How did your time at Wesleyan influence your writing of this book, if at all?

P.B.: I was a College of Letters major—a multidisciplinary program in history, literature, and philosophy. And later I in fact realized that I do very much think in a multidisciplinary way. [For The Barbizon as well as for my first book, The Greengrocer and His TV: The Culture of Communism After the Prague 1968 Spring], I was comfortable accessing different types of sources—looking at literature, artifacts, the written historical record, whatever it might be. College of Letters ended up being a real foundational building block for how I think, write, and research today.

But my most significant influence from Wesleyan was my core group of friends, who remain central in my life. They are the ones I bounce ideas off, and with whom I celebrate all the key moments (including the publication of The Barbizon).

Top photo courtesy of Susan Camp. Paulina Bren portrait by Adam Patane.