President’s Letter: Pragmatic Liberal Education

Colleges and universities in the United States come in many forms, but one of their most distinctive elements is pragmatic liberal education. This form of learning—no matter what you are studying—combines the acquisition of specific skills (like literacy and numeracy) with understanding of how those skills fit into broad contexts. Rather than being trained how to be a cog in a machine, you are taught to understand how machines work within the systems in which they (and you) are embedded. Pragmatic liberal education in the United States has emphasized that in a diverse democracy, it is crucial that people develop the capacity to listen to those with views different from their own.

Today the relevance of that vision is being challenged on many fronts. There are those who claim that colleges are creating insular tribes adept mostly at canceling one another rather than promoting a diversity of viewpoints. Liberal learning, others argue, contributes to the divisiveness afflicting American society by reinforcing a sense of superiority—in turn inciting righteous indignation among those who feel elites with fancy diplomas are looking down on them.

Critics are not wrong to point out that biases exist in the American academy that can lead to contempt for those who speak its idiosyncratic lingo. They are not wrong to question whether professors are providing the tools of facile rejection under the guise of empowering critical thinking, paying lip service to academic freedom while expecting ideological or intellectual conformity. These are legitimate concerns for anyone who believes that education should liberate one from dependence on someone else’s thinking (even the teacher’s) and that learning should foster open-ended inquiry and self-reliance. Discussion of implicit bias on American college campuses—be it the focus on identity or ideology—is a positive sign that some are acknowledging and wrestling with this real problem.

Because liberal education is a path well-trod by elites, it can also seem to be the pathway to elitism, cementing economic inequality and enabling a fortunate few to assume an attitude of haughty privilege. At Wesleyan, we have a long tradition of pushing back against this proud parochialism, working across communities beyond the campus, knowing that real inquiry must be tested beyond the university. Lately, Americans have been fed a steady diet of stories about so-called woke students refusing to listen to points of view from outside the campus mainstream. At Wes, though, I’m more likely to find hardworking undergrads holding down jobs, or volunteering in their communities all while pursuing their diplomas. Among our alumni, I’m more likely to find productive nonconformists and practical idealists building companies and purpose-driven organizations. On campuses today you can certainly find examples of cancel culture, but you also find faith-based groups supporting health care workers, liberal arts students working with the incarcerated, and an impressive array of young people defending the right to vote.

“A pragmatic

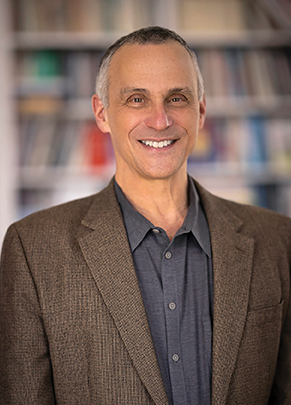

President Michael S. Roth ’78

liberal education promises to engage with issues that students will have to deal with beyond their university years; it’s more ambitious than a short-term training program.”

Higher education in the United States can be pragmatic without being conformist, and liberal education can inspire students to think for themselves in ways that include learning from people with views different from their own. A pragmatic liberal education promises to engage with issues that students will have to deal with beyond their university years; it’s more ambitious than a short-term training program. The problems confronting our world today cannot be tackled by technical specialization alone. Environmental degradation, artificial intelligence, public health, increasing inequality, international political tensions—these are complex areas that demand the kind of holistic thinking characteristic of liberal education.

At Wesleyan, liberal learning has placed a bet on what pragmatist philosopher John Dewey called “practical idealism,” a bet on the value of broad learning with the aim of contributing to a thriving society. Liberal learning requires open inquiry, deep research, and pragmatic approaches to the pressing problems and opportunities before us. As we continue to graduate practical idealists rather than narrow-minded conformists, we will be serving our students, the nation, and the world.