Ghost In the Machine

By using artificial intelligence to generate text that sounds like human-authored prose, ChatGPT signals a fraught new era for the written word. But instead of doomsaying over the potential for plagiarism in higher ed, Wesleyan faculty, staff, and students are working toward a better understanding of writing in the age of robots.

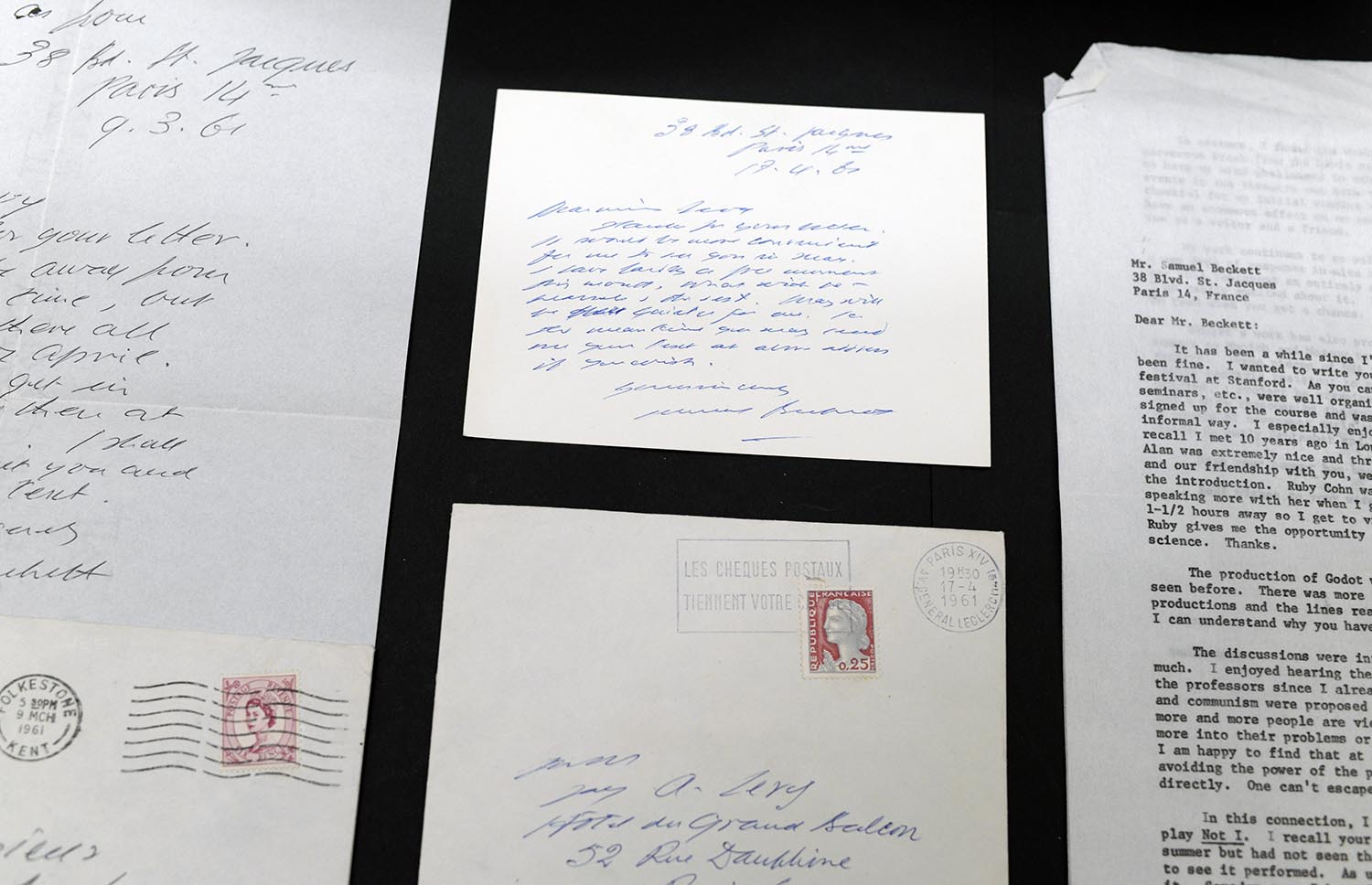

In late 2022, Anna Tjeltveit ’23 saw her Twitter timeline light up with talk of ChatGPT, a just-released, artificial-intelligence-powered chatbot that generates natural-sounding text from simple prompts. Not long after, her housemate created a ChatGPT account, becoming one of the more than 100 million users who logged on within two months of its launch. He typed into the prompt box: “Give me a list of ideas for a novel about environmental destruction set in East Germany in 1984”—the very novel that Tjeltveit was in the middle of writing.

In a matter of seconds ChatGPT provided a list that was, in Tjeltveit’s opinion, “stupid and generic.” It’s not that Tjeltveit, an English major and Writing Workshop tutor at the Shapiro Center, condemns ChatGPT. She’s used it to discover information that eludes Google searches (“find Central Asian underground music from the 1970s”) and says it’s great at writing the kind of copy you’d see on LinkedIn posts. But “the idea of using it to produce writing that I would ever put forth into the world is something I still feel very opposed to.”

Whether you’re a critic or a true believer, one thing is clear: ChatGPT represents a big, shaky step forward for AI. Seemingly overnight and without a blueprint, Wesleyan and other higher education institutions have had to react to something that can produce serviceable, ostensibly original academic writing—whose AI authorship is hard to detect—with little more than a few keystrokes. Naturally, there are thorny questions about academic integrity in an age when students can outsource their assignments to robot writers.

But as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Bard, and other generative AI technologies take the spotlight, their role in higher education demands a reckoning that goes deeper than matters of plagiarism. “When a professor puts their midterm prompt through ChatGPT and it returns an A-plus answer, that professor has to wonder: What are my learning objectives, and how did AI fulfill them without taking my class?” says Lauren Silber, assistant director for academic writing. “What are the values underpinning what I consider A-plus writing and how did AI know those were my values? ChatGPT makes us ask hard questions about whether we want to keep our educational values and writing standards or change them, and why.”

APOCALYPSE NOW (AGAIN)

When Mary Alice Haddad, John E. Andrus Professor of Government, tested out ChatGPT by typing a variation of a key essay question on her Japanese Politics midterm—name one way that Japanese democracy is different than American democracy in 500 words—the chatbot’s B-plus response left her terrified at first: “I thought, I’m going to have to go back to blue-book, in-person exams.”

By early 2023, other educators were growing restless too. Headlines swirled about ChatGPT passing MBA exams, being banned by New York City’s public schools, annihilating white-collar work, and supercharging the spread of misinformation. During the Fall 2022 semester, suspected use of generative AI led to at least one Wesleyan student referral to the Honor Board. But when her Wesleyan colleagues asked about a ChatGPT boilerplate for their spring syllabuses, Haddad, who is also director of the Office of Faculty Career Development, pumped the brakes: She thought making University-wide policy without a fuller understanding of the technology would be a bad idea.

“For professors, the first response is often fear,” she says, “but actually, there are a lot of positive aspects here.”

Higher ed has been weathering technological apocalypses since the invention of the calculator. “We survived the introduction of Wikipedia,” says Andrew White, Caleb T. Winchester University Librarian at Wesleyan. “The use of an internet browser to find information about anything at any time of day is only about 25 years old, and we got used to that pretty quickly.” And whether spell-check or Grammarly, use of AI writing tools has been largely uncontroversial until now. In some ways, ChatGPT is just autocomplete on steroids: By processing massive amounts of digital data, the algorithm uses the material it has “read” to predict the words satisfying a user’s query.

That said, these technologies could impact the entire University, from computer science assignments to admission essays. “My sense is there’s concern, but there’s a real hunger for guidance,” White says. He and Haddad were part of a small group of Wesleyan staff and faculty from across departments who convened, collaborated, and hashed out solutions for emerging anxieties around generative AI. Distilled into the Library Guide to ChatGPT, these suggestions include tailoring prompts more specifically to the class subject matter, scaffolding assignments—in which students submit outlines and rough drafts to trace their thinking and effort leading up to the final project—assigning non-research-paper projects, and using ChatGPT responses as a starting point to critique and highlight the information it excluded or flubbed. (The current crop of AI detection tools, the guide says, are not fully reliable.)

A handful of Wesleyan faculty have already addressed ChatGPT in their syllabuses. In her spring 2023 Empirical Methods for Political Science course, Erika Franklin Fowler, professor of government and director of the Wesleyan Media Project, required students to disclose their use of the technology and accept responsibility around issues of accuracy and plagiarism. She discussed with her students ChatGPT’s limitations and hazards, namely its penchant for producing convincing prose riddled with basic factual errors and seemingly real, totally fictionalized sources.

“Our students need to know how to responsibly use tools that are accessible to them,” Fowler says, voicing a distaste for a full ChatGPT ban common among higher ed faculty. “If we don’t allow them to learn to explore, then we also potentially put them at a disadvantage compared to those who do.”

Judicious use of ChatGPT isn’t just for students: professors can write first drafts of syllabuses, or, as Haddad recently did while writing a literature review, use it like a research assistant. (“I could bat around ideas as I was writing, and it helped crystallize concepts in ways that were really useful.”) And just as performance expectations grew once search engines streamlined the academic research process, the era of generative AI could similarly raise the bar for students and teachers alike.

“If you’ve been teaching for a long time, it’s very troubling to think that, suddenly, you can’t use the midterm that worked great for 15 years,” says Haddad, who plans to change her Japanese Politics midterm after her spring sabbatical. “There are some assessment modes that are very vulnerable to this new technology.”

Haddad accepts that some percentage of today’s students will use ChatGPT the way past generations turned to essay mills. But one of the privileges of working at Wesleyan, she says, is that her students are largely engaged with their studies for intrinsic reasons. She compares liberal arts students cheating with ChatGPT to trying to get in shape but hiring someone else to lift the barbell: It’s a waste.

“ChatGPT actually makes it more obvious why a liberal arts education is useful for this moment,” Haddad says. “We train people to create a future for themselves by getting them to be flexible, to teach themselves, to apply what they learn in practical ways, to create the jobs they want and not just get hired to do them. Other places teach you how to follow in a path that someone else has made. But liberal arts students can turn on a dime, go in new directions, and use disruption as a positive force in their lives.”

THE VALUE OF IMPERFECTION

Ultimately, the way students choose to use ChatGPT reflects a fluctuating calculation of what academic effort is worth. The same student might happily write a 25-page research paper without AI help if it captivates them, then turn to AI to draft a discussion post for a course they’re slogging through. “Students are political actors,” says Marcus Khoo ’23, a Writing Workshop tutor who studies psychology and education. “They’re always negotiating at which points they buy into a class and commit to the intellectual journey, and at which points they say, ‘I’m in college to get a degree and move on with my life.’”

AI has already demonstrated less-publicized benefits. Chatbots have helped students with mental health issues find services and support. At Georgia Tech, an AI chatbot helped reduce the number of newly admitted students that dropped out before the start of the semester by 22 percent. Silber conveys a sentiment about ChatGPT familiar to many of her students struggling with the conventions of academic writing: Now I can sound the way my professors want me to sound.

But by reinforcing those conventions—the clean-but-formulaic sentences, the sparkling prose that could be authored by anyone—ChatGPT indirectly questions the true value of that voice. “If a computer can produce this kind of language, do you want your students to produce it too, or do you want to hear their own language even if there are hiccups?” Silber says. When colleagues say ChatGPT creates good writing, Silber says, “It makes me a bit worried, and maybe a bit sad, that sometimes we normalize language so much that we miss out on the vibrancy of difference.”

Focusing on writing as a polished product, meanwhile, also obscures its larger role in higher education. If students can avoid fumbling through flawed arguments, incomplete analysis, and the other messy parts of the writing process—time-consuming efforts that aren’t always visible in the final draft—why shouldn’t they?

“If our pedagogy, our University, and our professors cannot make a case for why you should be engaged with writing, over the convenience argument that ChatGPT implicitly produces, that’s a massive existential problem that needs collective negotiation,” Khoo says. “If that doesn’t happen, we’re on the back foot with regard to how to adapt, because the technology is just going to keep growing.” (Within four months of ChatGPT’s arrival, OpenAI introduced an update trained on exponentially more data.)

The question of generative AI, Khoo says, “is a societal, collective conversation around: How do we as an institution think about writing?” It demands open discussion and continuous reexamination, balancing the perspectives of industries where these technologies are being used as well as those of incoming students. (“Young people . . . are going to have the most knowledge on how to use ChatGPT, and also the most knowledge on why to use it,” Khoo says.) And while there are no one-size-fits-all solutions, modernized introductory writing courses that address the ethics of AI while helping students build personal, emotional connections to the writing process could provide a start.

The extent of generative AI’s influence, on higher ed and points beyond, remains an open question. But in these early days of grammatically correct robot writing, Tjeltveit emphasizes the value of the awkward phrases and clunky sentences we generate ourselves: They’re the signs of human intellects trying to figure things out.

“I believe so strongly that writing is thinking, that writing is a process, and that writing can be interesting because of its mistakes and points where it isn’t clear,” Tjeltveit says. “To be honest, the kind of writing that I consider valuable is something I don’t think ChatGPT would be able to do in a million years.”

(A)I Come In Peace

(A)I Come In Peace

With lots of speculation on what generative AI means for the world beyond higher education, Hong Qu ’99—one of YouTube’s first software engineers, now a Harvard Kennedy School adjunct lecturer specializing in ethics and governance of AI—weighs in on the limits of ChatGPT, its impact on industry, and whether we’re nearing meaningful regulation.

On responsible use of AI: “ChatGPT displaces what I would say is low-stakes work, where it doesn’t have to be 100% correct. But anything higher stakes that impacts people’s livelihoods and life opportunities—once you delegate a decision to AI, it will produce the final product, but you won’t have much influence over it. If something goes wrong, who bears responsibility? So much goes into the ChatGPT answer process and it’s very difficult to identify who has liability.”

Action vs. intent: “[A major limitation of ChatGPT is] it cannot cite sources. Even if it does create some sort of lineage of where the ideas in its response came from, how do we know its intent? This AI will do its best to provide a decent answer to your question, but it doesn’t have a self-propelling way of directing its own behavior. Maybe in the future it will, but that may be many decades or even centuries away. If it doesn’t have intent, it can’t be self-aware to say, ‘That’s why I put [this information] into this answer.’”

Oversight and funding: “There’s been talk about having an external standards body empowered to regulate AI and set ground rules. European regulators are the closest thing to it—they’ll impose billion-dollar fines, but even they cannot be a counterweight to tech platforms who don’t mind paying billions of dollars and don’t mind negative press. The technology [seems like it] changes every two weeks, and you can’t write new laws every two weeks. I’m pretty pessimistic: I feel like for-profit enterprises that have the biggest wallets ultimately steer the ship, and we’ll be catching up to fix the spillover effects.”