The Making of a Good Citizen

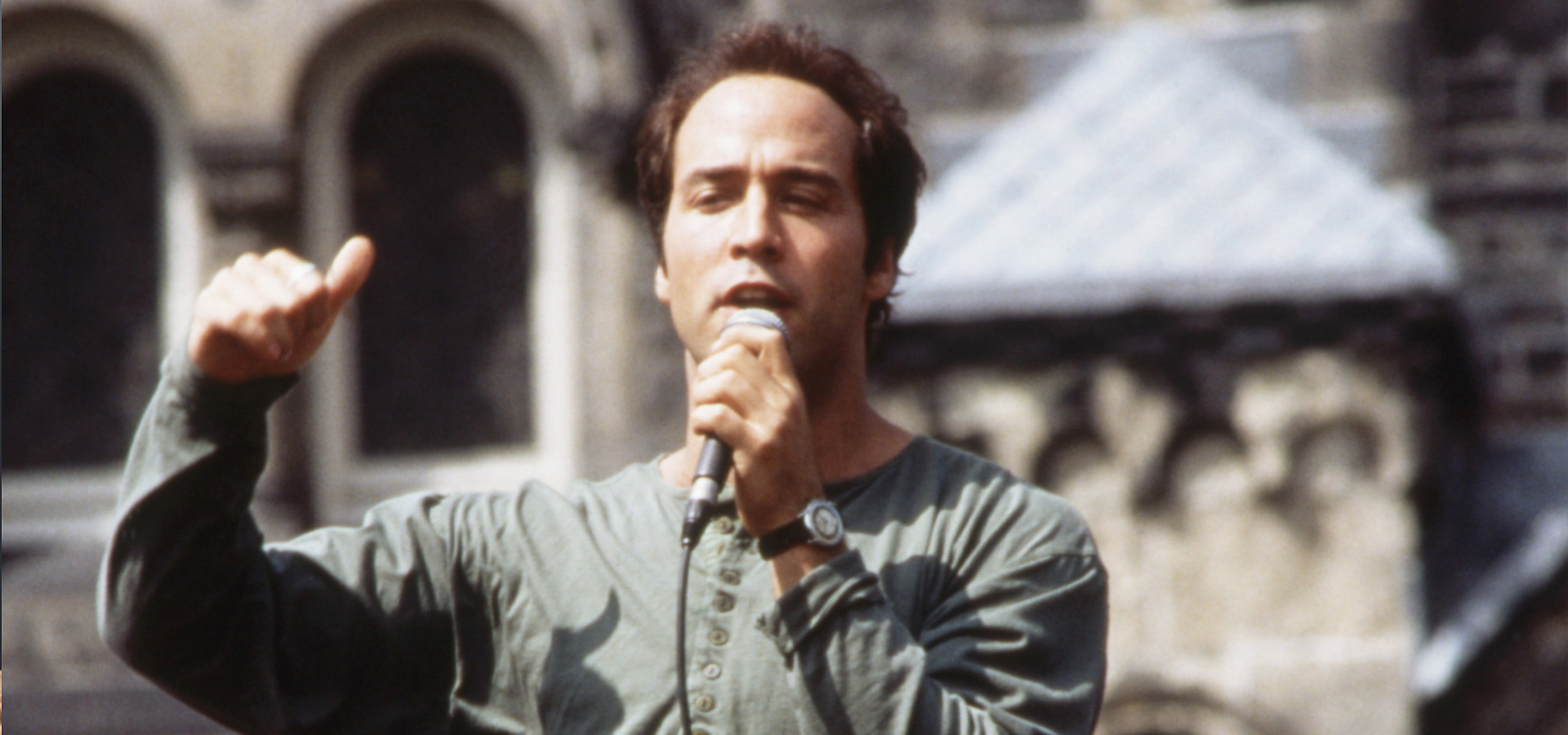

Shaking up the way politics is covered is nothing new for Robert Allbritton ’92, founder and former publisher of Politico. But with the newly formed Allbritton Journalism Institute, he’s going back to the basics—producing a new generation of skilled journalists who uphold democracy by providing unbiased reporting that simply informs.

If you ask Robert Allbritton ’92 if he could have predicted during his days at Wesleyan that he would alter the way political journalism in the United States is practiced—and by extension the way Americans consume political news or make decisions about candidates and policy—he’ll tell you no.

But that’s exactly what the former publisher of Politico, the politics-based digital newspaper he co-founded in 2007, did. Now, he may be poised to do it again. With his latest project, Allbritton Journalism Institute (AJI), and its attendant news arm NOTUS—short for “news of the United States”—Allbritton is applying a dual-pronged approach to journalism, in part, to center objectivity in a field where it has been waning in recent years. In fact, a study out of the University of Rochester found ideological bias in stories about domestic policy and social issues in 1.8 million headlines across major news outlets between 2014 and 2022.

But as significant a problem as that is, other factors contributed to Allbritton’s founding of this joint news academy–journalism platform model, too: The number of local newsrooms around the country is diminishing, which means there are fewer reporters left in the pipeline to graduate to national outlets; the seeming perpetual logjam in Congress hamstrings the government so that little gets done; and the reality that, though initially frustrating, Politico became a feeder publication where journalists worked before moving on to news outlets with larger audiences.

“We need to create a pipeline of folks that can populate serious (news) organizations that reach large numbers of people, or reach very influential audiences, reporters who are going to be impactful and who are going to write the pieces that are going to hopefully rekindle civil discourse in America,” he said. “One of our mantras is, ‘Democracy needs journalism.’”

It started with Politico

The idea of launching what would become Politico was initially just “a nice little side business” for Allbritton, who was chairman and CEO of Allbritton Communications at the time. But during early discussions about what kind of publication to create, an editor, who became a Politico co-founder, introduced a novel way to cover American politics: Deliver fun, lively, and detailed takes on politics for the people addicted to reading about it. Once Politico hit its stride, it earned a reputation for scoops and political analysis. But mostly, the publication got attention for its trademark fast-paced, inside-politics coverage of the Beltway that other long-established outlets then emulated.

“We always said we want to be the ESPN of politics,” Allbritton said. “ESPN is interested in the best play of the day, but they don’t have a favorite team. They’ll call balls and strikes. . . . I just wish that more of our countrymen could look at politics through that lens.”

Politico may have introduced a different energy to Washington, D.C., but it got its share of criticism, too. Some people labeled it gossipy. Others criticized its sports-like approach to political coverage. But Allbritton saw bigger culture shifts made possible through the publication. “We made an impact. We certainly raised the pay for star journalists. I think we changed the pace of reporting.”

By the time the German-based media company Axel Spring SE came knocking, Allbritton was ready to sell (the deal was finalized in 2021). During negotiations, he began formulating ideas for what would be his next venture: AJI and NOTUS. If Politico was about policy and politics, then NOTUS would be focused on questions like, Why is Washington the way it is? And what drives the people who make it so?

Flipping the script

Traditionally, national news reporters gained their reporting experience on the local level. But with local newspapers shuttering at an accelerated pace and the ones still standing slashing staff, there are fewer opportunities for reporting hopefuls to get their first jobs, really learn the craft by the side of seasoned editors and, for those who are interested, move on to national publications. The State of Local News 2023 report by the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University detailed just how stark the problem is. Since 2005, nearly 2,900—or a third—of the local newspapers in the United States have disappeared, while nearly 43,000—or two-thirds—of local newspaper journalists have lost their jobs.

As Khalilah Brown-Dean, the new executive director of the Allbritton Center for the Study of Public Life and university professor, explained during Wesleyan’s Democracy in Action convening in February, the dearth of local newspapers and reporters has important consequences for society. “That loss of local media, local journalism, really creates disincentives for people to engage,” she said. “Because it’s easier to be in the echo chamber, it’s easier to say . . . the border crisis is happening far away, without thinking about the immigrant families who are right here in Middletown, who often become targeted just because of who they are, and are totally disconnected from the discourse but feel that impact.”

While American politics has been battered and a contentious ideological divide pits citizens against citizens, Allbritton is optimistic about the part unbiased reporting can play in strengthening our democracy.

“There are some things, on a national basis, we just don’t agree on. But I think there’s more that we do agree about. So, we can write those pieces,” he said. “I don’t want to say they’re feel-good stories. They’re not. It’s just that (we have the) ability to deliver a hard truth in a way that’s digestible.”

If the concept for AJI seems lofty, the institute’s mission is simple. The homepage reads, in part, “The institute is staffed by a group of veteran journalists who are committed to improving journalism and democracy.”

Allbritton said he took inspiration for the AJI-NOTUS structure from the medical residency experiences of his wife, Elena Allbritton ’93. An English major at Wesleyan, she went on to become a doctor. “The way they teach physicians kind of struck me. They have a teaching hospital where, as a young resident, you are paired up with a senior physician and you work with them and you slowly get turned loose and eventually they’ll let you operate on humans,” he said. “But there’s no teaching hospital for journalists. There’s nothing like that.”

In most journalism schools, Allbritton said, the majority of the learning is done in the classroom, not in the field, which is where he thinks most of the lessons come from. Allbritton’s model grants early-career reporters two-year fellowships with AJI, where they learn from seasoned Washington, D.C.–based journalists who help them hone their skills and earn bylines in NOTUS.

“We wanted to flip that script,” he said. “We wanted to make it a majority doing, working with those great editors and some classroom work to get (reporters) up to speed.”

In most journalism schools, Allbritton said, the majority of the learning is done in the classroom, not in the field, which is where he thinks most of the lessons come from.

An act of democracy

Allbritton sees his AJI-NOTUS combination as providing an antidote to the training deficit caused by the decline of local news outlets. In his analysis, some of the factors leading to the demise of local news lie in newspaper business models and don’t apply to internet-based publications like NOTUS, which supplies news based on readers’ interest, not their geographic location. Additionally, he believes taking a centrist approach to the news will give reporters the credibility to inform the public, and that informed citizens make good citizens.

“I think if you begin to understand the other side’s point of view, rather than just making it the villain, that’s where we get to the point of compromise. We’re not going to agree. But we can go back to being the loyal opposition, as opposed to being the enemy of the state, which is the current direction,” he said. “That is problematic for democracy in the long-term.”

The way Allbritton sees it, though, what may be a salve for an ailing democracy won’t change things overnight. Instead, AJI will educate young journalists in a way that will plant seeds of change as they move through their careers and onto different outlets. Whenever it happens, he believes change is imperative because American democracy has been weakened. (“Failure was not an option for the United States’s democracy, until now.”) He added that the way news organizations frame information has an impact on the way people consume that content and that affects democracy, sometimes negatively.

“When any one of the national (news) organizations is clearly using the politics of division to advance their business, that is bad for the country, especially if you are really representing the fringe point of view and portraying it as a national point of view,” he said.

Allbritton and his team deliberately set out to hire people with different points of view to staff AJI. “This is about diversity of thought. That is the entire point of this exercise,” he said. “When we were setting this up, we realized certain groups of folks want to get into journalism because they have a certain bias to them, people who want to be conservatives and others that want social justice. Well, good for you. But we’ve also got to teach you how to tell both sides of the story.”

So, does Allbritton consider his latest endeavor also to be a bit of activism? Not exactly. “That’s too much high horsey for me. I think if you want to make a difference, figure out what you’re good at and go do that. Just do your part,” he said. The banker who finances jobs that keep the economy going, a lawyer who defends innocent people, the cop on the beat who keeps people safe, the people who serve in office—all play a part that keeps democracy going.

With the creation of AJI and NOTUS, Allbritton has played his part. He hopes that, 20 years from now, the organizations will be playing theirs by being “a feeder for major publications with super high-quality reporters and editors who have that independent point of view and who can speak both authoritatively and convincingly in a way that can simply open eyes a little bit, instead of having hard teams left and right.”

That, he said, can have a positive impact on our society—and our democracy.

“This is about diversity of thought. That is the entire point of this exercise.”

Robert Allbritton ’92

AJL’S FIX FOR AN AILING DEMOCRACY

(Excerpted from AJI.org)

WHAT PROBLEM IS AJI SETTING OUT TO FIX?

America’s journalism-training model is broken. Thousands of local newspapers have shut down in recent years. That means the jobs where young journalists traditionally trained for their careers—reporter positions at local newspapers—have largely gone away. Meanwhile, graduate programs in journalism are expensive, and therefore mostly unrealistic for students who aren’t from wealthy backgrounds or who don’t want to borrow money.

No wonder the press corps doesn’t look like America—and, as a result, so many Americans distrust the press. No wonder the media is struggling to play its role as a defender of democracy. No wonder both American journalism and American democracy are in grave peril.

WHAT IS AJI DOING ABOUT THIS PROBLEM?

AJI has created a powerful new model to fix the broken market in journalism training: an institute that functions as a teaching hospital for journalism—a newsroom where early-career journalists learn on the job while taking classes with some of the best reporters and editors in the country.

SO HOW DOES THIS WORK EXACTLY?

In addition to learning on the job, our fellows have the opportunity to study in a classroom setting with journalists who are simply the best at what they do. From Tim Alberta of The Atlantic, to DeNeen Brown and Josh Dawsey of The Washington Post, to Pulitzer winner Wes Lowery—and many more—our faculty, mentors, and editors are working journalists who are currently at the top of the profession.

Moreover, by offering fellows a $60,000 annual stipend, and by recruiting systematically at colleges and universities nationwide —instead of just waiting for applications from students at the usual elite institutions—we ensured that the first class of AJI fellows was extraordinarily diverse: socioeconomically, geographically, educationally, and ideologically.

WHAT ARE THE RESULTS SO FAR?

Our first class of fellows describe AJI as an “awesome opportunity” that is “truly unique,” “a chance to be sharpened by journalists at the top of the game.” AJI faculty and editors, says one fellow, “have invested so much time in me individually, something that editors in big newsrooms simply do not have the capacity to do.”

By Lorna Grisby