WESLEYAN RESPONDS TO SYRIAN REFUGEE CRISIS

Last fall President Roth took what some thought was a risk. Appalled by the Syrian refugee crisis, he issued a challenge to the Wesleyan community, asking what can we do?

How would people respond? Would they say that’s not Wesleyan’s business? Ask why this crisis and not another? Demand more of Wesleyan than it could possibly do? In fact, the Wesleyan community made some good suggestions which the university has been able to act upon, doing the kinds of things it does well:

- Hold panel discussions to increase understanding and awareness

- Sponsor student internships with organizations assisting refugees

- Host a refugee scholar on campus, and enroll a refugee student

- Work with local officials to welcome refugee families to Middletown.

These are the four components of Wesleyan’s Refugee Initiative. Roth had hoped that other universities might follow suit with comprehensive and highly public initiatives of their own, but Wesleyan has remained an outlier. It is not alone, however, for in the decision to do something in the face of this horrific crisis Wesleyan has found itself in the company of a number of extraordinary organizations. One of those organizations is home grown, the Wesleyan Refugee Project (WRP) founded by seniors Cole Phillips and Sophie Zinser and junior Casey Smith, and its work together with University efforts have just been featured by the U.S. Department of State as part of its new toolkit for refugee engagement.

Providing an education dedicated to boldness, rigor, and practical idealism is Wesleyan’s mission, and the panel discussions on the refugee crisis fit right in. They were put together by Rob Rosenthal in his capacity as director of the Allbritton Center for the Study of Public Life, and in consultation with the WRP.

Bruce Masters, John E. Andrus Professor of History, led off the first panel in February. An expert in the modern Middle East, PAC 01 was filled when Masters stood up to speak: no notes, no PowerPoint, no hesitation, no agenda other than that of the historian: to explain how the horrific state of affairs in Syria had come to pass. It was a complicated story made accessible by the historian who knew it so well, and the audience was riveted. Syria was a tragedy, no escaping that, and it was a tragedy that was going to get worse. Masters added a personal touch, indicating that he had built relationships with over a hundred Syrians, of whom not a single one has remained in the country.

Personal experience was even more central to the presentation of the next panelist, Robert Ford, who served as U.S. Ambassador to Syria from 2010 to 2014. The students were clearly excited to meet him. Ford described perilous encounters with regime supporters angry that he had spoken out for human rights and provided an insider’s view of diplomacy and its limitations. One of the most striking of his assessments is that the U.S. has been overly focused on Assad himself. The far greater problem, according to Ford, is the entrenched power of a thuggish secret police, which because of the atrocities it has already committed, knows it cannot compromise and expect to survive. The final speaker was Marcie Patton, Fairfield University Professor of Politics, who described the situation with respect to Europe and especially the politics and political economy of Turkey.

A second panel, two weeks later, focused on the refugee experience and began with remarks by Steve Poellot, Legal Director of the International Refugee Assistance Project. Who is a refugee? Who decides who is refugee? What does ending the experience of a refugee look like? All these questions are very much mediated by the law, Poellot explained. But not every case is clear-cut, and his organization helps refugees navigate the legal system.

Poellet was joined on the panel by two Syrian refugees. Basileus Zeno arrived in the U.S. in 2012 on a student visa to study archaeology, and in the years since then he has watched from afar as his colleagues at home were kidnapped, imprisoned or killed – including his mentor overseeing the ancient ruins of Palmyra who was beheaded by ISIS. His friends found themselves drafted into various groups (more by happenstance than by ideology), and now most are dead. He has applied for asylum here and cannot leave the country lest he not to be allowed to re-enter. Now a Ph.D. candidate in political science at University of Massachusetts/Amherst, Zeno was distressed by the fact that the countries that have spent the most money on sending arms into Syria are by and large those that have accepted the fewest refugees, with the U.S. at the top of that list. There is a great deal of unwarranted fear of refugees in this country, he finds, and he harkened back to an analogous situation in 1939 when the U.S. turned away Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler and sent them back to Europe.

Mohammed Kadalah, who taught Arabic at Wesleyan last year and is now at UConn in the Department of Literature, Cultures & Languages, was recently granted asylum after fleeing Syria in 2011. Had he returned to Syria, he explained, he would have been drafted into the army “to shoot innocent people” or be shot himself, and he “was interested in neither.” Much of his family remains in Syria, but he has lost contact. He observed that it was Assad’s regime that was the first to play the “Islamization” card, using a trumped up claim that Kadalah’s hometown had declared itself an “Islamic State” as an excuse to bomb it. The more “simplistic” the narrative, he stated, the more you can mobilize people and the more money you can raise from outside.

Nor has there ever been a strong civil society in Syria, no idea of people governing themselves. There’s only the State. There had been sub-nationalities, of course, but these had not been of particular importance; it was violence that changed people’s perceptions of themselves and led to the fragmentation we see today. By now, he concluded, most of those who launched the revolution have been killed, and a great many of those doing the fighting are just kids who have been brainwashed.

Zeno and Kadallah expressed thanks to the communities in New York and Connecticut that welcomed them. When a student from the audience asked how much refugees cared about which locales in the U.S. they were sent to, the panelists agreed that where doesn’t matter; what matters is safety. Syrians are having to choose among only terrible choices, and the panel ended with a quotation from Somali-British poet Warsan Shire: “You have to understand, no one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.”

The third and final panel (March 31) was about the U.S. response to the crisis, and the audience was composed of students and people from Middletown eager to help in some way. The panel began with a video message to the Wesleyan audience from U.S. Senator Chris Murphy, who thanked “Wesleyan for stepping up to the plate and convening this panel.” Citing the awful conditions of the refugee camps in the Middle East, Senator Murphy argued for the U.S. to play a bigger role in resettlement. The Senator’s Outreach Assistant, Ben Florsheim, Wesleyan class of 2014, was the first panelist to speak, and he reiterated the importance of citizens letting their political representatives know how they feel. After the Paris attacks, the Senator’s office was inundated with demands to halt the resettlement of refugees. Florsheim emphasized that, while senators have their own views, they also feel responsible to represent their constituents, so it’s important for those who in favor of welcoming refugees to write in and express support for that.

Panelist Jen Smyers, Director of Policy and Advocacy at Church World Service, described resettlement of refugees as “our oldest and most noble tradition” – as for refugees the option of last resort. Returning to their country of origin (as soon as it’s safe to do so) or integrating into nearby countries that share their culture or language are both preferable, but at this moment, neither option is viable. That leaves only resettlement. Yet America is backing away from resettlement, and Homeland Security is adding extra layers of vetting, slowing things down.

Smyers lamented “fatigued empathy in the U.S.” and emphasized the degree to which refugees from Syria (or Central America, or elsewhere) were economic engines – and regardless – deserved to be treated with dignity on humanitarian grounds alone. That they represent a danger is a myth. Refugees are the most vetted individuals in this country, and this was a point picked up by the next speaker, Chris George, director of Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) in New Haven who added that if the U.S. won’t at least fulfill its own (rather limited) commitment to help, other countries won’t fulfill their commitments to help either. IRIS finds and furnishes apartments for refugees in New Haven and sometimes jobs to get them started.. George praised to the skies the Wesleyan Refugee Project students who have been volunteering with his organization helping refugees. “The Wesleyan students have been wonderful,” he said, “they learn quickly and work independently and don’t overstep their bounds.”

Finally, Christina Pope of Welcoming America (where Wes alum David Lubell is executive director) spoke about the necessity of adaptation, not just by the refugees but also by the communities they come to. Pope emphasized the importance of citizens establishing meaningful personal contact with refugees if the predictable backlash of anti-refugee sentiment is to be avoided.

Looking back, Rosenthal judged the panels “heartbreaking because the situation is so dire, but also wonderful , both because they provided an immediacy to the crisis that most of us in the United States don’t experience, and because the final panel brought news of what can and is being done on a local level to respond to the crisis.” He added “It was also quite wonderful to hear from a number of speakers how much they already appreciated the work of Wesleyan students, particularly the Wesleyan Refugee Project.”

“Do some good.” Words spoken softly by Professor Masters on his way out the door at the conclusion of the first panel discussion. He was looking at students Phillips, Smith, and Zinser, whom he knew were interested in assisting refugees in Jordan. It wasn’t clear that the three, engrossed in excited conversation about the panel discussion, even heard him. But it turns out, thanks to Wesleyan’s sponsoring of internships and to the WRP, they will have new opportunities to “do some good” in the ways they want.

Phillips helped out with the Collateral Repair Project (CRP) in Amman Jordan last year, and his experience there assisting Syrian and Iraqi refugees has inspired a number of his fellow students. Now the internship support will enable him to return this summer to manage the CRP’s programs and volunteering. The executive director of the CRP visited Wesleyan last semester (a visit facilitated by Phillips), and her talk here inspired rising sophomores Isobell McPhee and Willa Schwartz to intern with that organization as well; they will work in the emergency assistance program and help with English studies and computer classes to help refugees acquire the skills to find sustainable jobs in Amman. Casey Smith worked at the CRP and the International Refugee Assistance Project last semester, and now she will go to Washington, D.C. to intern at the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, the branch of the State Department focusing on refugees.

![Event organizer Sophie Zinser ’16, a College of Letters and French studies major and student fellow for the Center for the Humanities, made connections with the Amal Foundation in December 2015. The organization supports refugees and their host communities by offering them access to education. “I had no idea that months later [Amal and the Wesleyan Refugee Project] would be planning a show together, bringing art from Za’atari here to Wesleyan. We have made it our mission to represent these artists as if they could actually be at Wesleyan,” Zinser said. Photo: Olivia Drake MALS ’08](https://magazine.blogs.wesleyan.edu/files/2016/05/eve_refugeeart_2016-0504172033-1024x683.jpg)

“I had no idea that months later [Amal and the Wesleyan Refugee Project] would be planning a show together, bringing art from Za’atari here to Wesleyan. We have made it our mission to represent these artists as if they could actually be at Wesleyan,” Zinser said. Photo: Olivia Drake MALS ’08

She also just published an article in the last Wesleyan Magazine on a Syrian literary scholar who the Center for Humanities expects to host next fall, when its theme will be “Hope and Hopelessness.” This scholar will receive what is essentially a postdoctoral fellowship, and it too has been funded by Wesleyan’s Refugee Initiative. The university is also committed to working with the Institute of International Education and Jusoor, an NGO of Syrian expatriates, which have partnered in putting together the 100 Syrian Women Scholarship. In another month or so, Wesleyan will know if it has a Syrian refugee in the class of 2020.

Finally, for refugee efforts right here in Middletown, students Peter Dunphy and Serene Murad were awarded internship support to help Wesleyan’s Center for Community Partnerships work with City officials and church leaders to welcome refugee families to Middletown. The Center’s director, Cathy Lechowicz, indicates that the coalition has at least a dozen different faith based groups, civic organizations, and over 70 volunteers. She describes it as “an incredibly humbling and gratifying experience to partake and support this effort as it is emblematic of true partnerships.” On May 11 the effort begins to pay off as Middletown welcomes the first of several refugee families. It’s an Iraqi family of six: father, mother, daughter (15), and three sons (7, 5, 3), and already Wesleyans like Bruce Masters have offered to help as translators. “I am proud,” says Lechowicz, that Wesleyan has dedicated resources and energy to raise awareness about the refugee crisis and actively work to meet immediate need.”

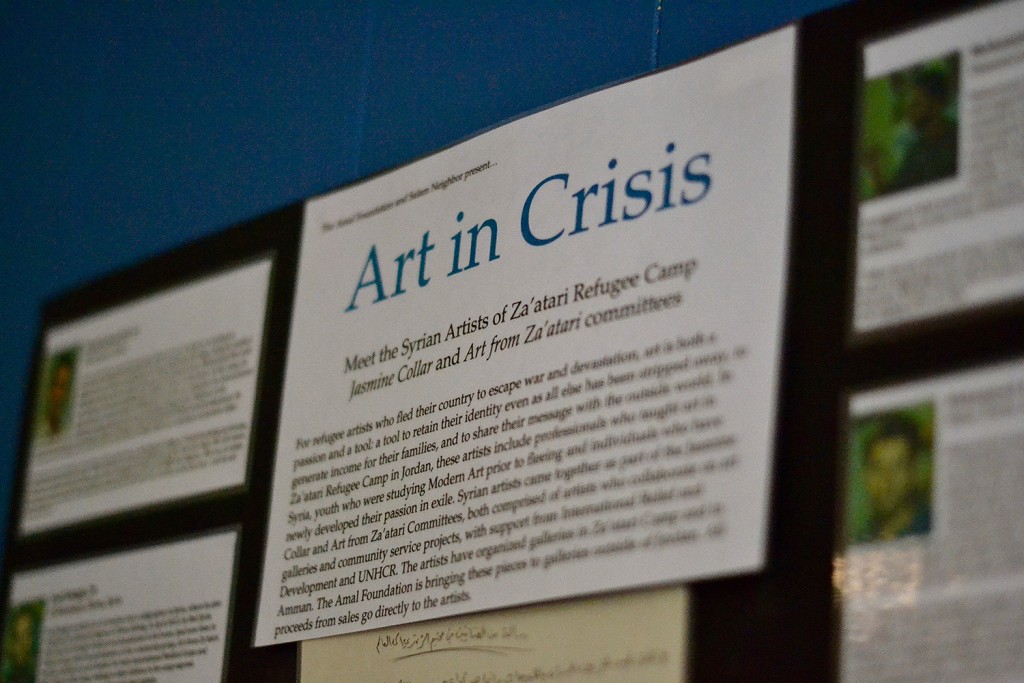

The work with refugees in Middletown is ongoing, even as the particular initiative launched by President Roth winds down. And students continue with their own efforts. The WRP has been volunteering twice a week at Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services helping Connecticut-based refugees complete applications to energy assistance and subsidized housing programs, helping Iraqi refugees complete their applications to resettle in the United States through the International Refugee Assistance Project, and tutoring displaced Syrian students over Skype through Paper Airplanes. As part of WRP, senior Sarah Rahman and a team of passionate students have organized a number of events on campus to fundraise for a scholarship for a refugee student living in Za’atari Camp through the Amal Foundation. Just this past week brought to campus an art show called “Art in Crisis” featuring works by artists in Za’atari Refugee camp, the largest refugee camp in Amman. These works are currently on view in the Center for the Humanities and will be sold in a silent auction with all proceeds going via the Amal Foundation to support the artists in Za’atari.

With this exhibition the students of the WRP have given their peers, their teachers, and Wesleyan staff and alumni (including those here for Reunion) yet another remarkable opportunity to participate in what has been a wide-ranging effort to “do some good” in the face of a horrific crisis. Seven months ago President Roth asked “what can we do?” and Wesleyans continue to answer.