America’s Most Innovative Rancher

BY GABRIEL POPKIN ’03

Anya Fernald ’98—dubbed “The First Lady of Livestock” by Modern Farmer—is changing the way we think about carnivorous pleasures, with restaurants featuring cuts beyond ribeye and a cookbook capturing the warmth of traditional cooking experiences.

Fernald draws from a wide range of ranching techniques and fully owns her farm-to-butcher shop supply chain, allowing her to produce high-quality meat while embracing organic and animal welfare values.

By the time Fernald reached her senior year of high school in Palo Alto, California, she was sure she wanted a career involving food. Her Stanford University professor parents, however, were adamantly opposed. So Fernald hatched a plan. She had read in Smithsonian magazine about the Thomas J. Watson Fellow ship program and learned that Wesleyan was one of the schools whose graduates were eligible. She applied to Wesleyan early decision and got in.

Like most universities in the mid-1990s, Wesleyan didn’t offer much in academics to budding foodies. “Food was not a thing,” she says. “I was an outlier.” So Fernald made cheese in her dorm room, and in the middle of her sophomore year she took a year off to work in bakeries in California and Montana. “We were slightly horrified,” recalls Cecilia Miller, Fernald’s professor in a yearlong history course within the College of Social Studies. But thanks to her tenacity and smarts, Miller adds, Fernald was able to return to school and pick up where she left off. “She was able to pull off something that supposedly shouldn’t have worked.”

“The [CSS] professors were super-accommodating to what I wanted to do and really helped me succeed,” Fernald recalls. She wrote her senior project on the history of bread baking locally in Middletown, then applied for the one-year Watson fellowship to study artisanal cheesemaking. “I was totally confident I would get it, and that was my only plan. And I got it, thank god!” Travelers checks in hand, she left for the UK, Greece, Tunisia, and Italy, where she would wake up at 5 a.m., ride her folding bike to the train station and head to an artisanal dairy in the mountains. “I was nuts!” she says. “I wasn’t afraid.”

Fernald was entering a world where the distance from field to fork was measured not in thousands of miles but in meters. This was not because the villagers she spent her days with were part of some trendy locavore movement, but because their lives were built to a large extent around food—and often there were no nearby supermarkets. In her recently published cookbook, Home Cooked, (Ten Speed Press, 2016) Fernald recalls a spontaneous group outing on the Mediterranean to harvest sea urchins, while someone boiled a pot of spaghetti on the rocks for lunch. The bold tastes of ultra-fresh meat, fish, and dairy made a lasting impression, as did the communities that coalesced around such meals.

After the fellowship, Fernald spent two years in Sicily developing an effort to distribute cheese made by small producers to global markets and then ran an international grant program for Slow Food International, in the Piedmont region of northwest Italy.

CALIFORNIA DREAMING

Fernald returned to her home state in 2005. Much had changed since her childhood— farmers markets and community-supported vegetable farms were booming. But some things had not changed, at least not enough for Fernald. Getting locally raised meat, for instance, was nearly impossible. Fernald bought a cow and sold cuts from a van.

Drawing on her Slow Food experience, she started a local food consulting company and, a few years later, the Food Craft Institute, a nonprofit incubating local food businesses. In 2009 she launched the Eat Real Festival, a two-day food event in Oakland that draws more than 100,000 people each year. But Fernald did not just want to help others produce and sell food; she wanted to do it herself. She started looking around.

California has a way of amplifying dreams. Through Fernald’s consulting work, she had connected with Todd Robinson, a financial executive who had bought a few worn-out ranches in Siskiyou County, on the flanks of Mount Shasta. “He wanted to do something in the meat space,” Fernald says. She, meanwhile, had concluded that while plenty of people had shown it was possible to grow vegetables sustainably and profitably, “meat was the nut that nobody had cracked.” In 2011, with Robinson’s money and Fernald’s ambition, Belcampo Inc. was born.

Belcampo brings together worlds that are about as far apart culturally, if not geographically, as Wesleyan and Sicily. Siskiyou County is juniper and cattle country, but the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas provide Fernald’s core customer base. On the farming side, Fernald has taken inspiration from Allan Savory, a pioneering livestock farmer from Zimbabwe who believes that grazing ruminants in dense herds best mimics prehistoric savanna ecosystems. Belcampo’s approach to pasture management also echoes the practices of Virginia farmer Joel Salatin, who argues that a healthy pasture is the basis of healthy meat.

Belcampo’s team follows a sophisticated rotation for pasture management wherein roughly 2,000 cows graze around 70 percent of the standing forage, followed by pigs, and finally chickens, which eat insects and fertilize the soil.The pasture is then reseeded so the cycle can start again. Cows and sheep also spend part of the winter on another property owned by the farm, so they can eat grass year-round, and never hay or grain.

Pasture needs water, of course, and California farmers are being punished by a historic drought. Fernald sees this as the “new normal.” Careful thought goes into every aspect of water management, and employees are upgrading irrigation equipment so it will lose far less to wind and evaporation. When I visited on a hot, cloudless day, Belcampo’s pastures were green while most everything around was a crackling yellow. Soil fertility and grass growth is up 30 percent since the farm began, says Belcampo’s chief operating officer Nate Morr, and staff have led pasture management workshops for local farmers.

“SHE CAN FINISH HER COOKBOOK, DO A PHOTO SHOOT, TALK TO A CLASS OF FITNESS AND YOGA INSTRUCTORS ABOUT THE HEALTH OF MEAT, AND BE OUT ON THE FARM, GOING OUT AND MOVING CATTLE WITH US AND BE IN THE BOARD ROOM … ALL IN THE COURSE OF A DAY.”

A strong dose of biological technology is also embedded in the operation. Every cow and pig is genetically tested and tracked from birth to the store shelf, and meat is regularly analyzed for its ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids, a key indicator of nutritional benefits. When an animal produces exceptionally good meat, its parents are bred more often. Belcampo’s ecological practices go well beyond the USDA’s National Organic Program standards, but Fernald gets the certification because her customers value it. The farm is also certified Animal Welfare Approved, the industry’s most stringent animal care standard.

On the business side, Belcampo follows the tech-industry venture capital model of building up fast in hopes of earning big later. Robinson put an eye-popping $50 million into Belcampo, and Fernald hired the celebrity animal scientist Temple Grandin to design a 20,000-square-foot slaughterhouse. (Grandin’s reputation for animal welfare helps assuage customers, but staff have had to modify her design to accommodate their multiple species.) Belcampo has seven combination butcher shops and restaurants in the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas, and Fernald plans more. Most crucially, Belcampo owns its entire supply chain, from farm to slaughterhouse to refrigerated trucks to attractive retail outlets. This allows Fernald to capture value at every step, and, she hopes, stay true to her ethics even as she expands to a scale that most sustainable operations can only dream of. “It’s a pretty unique confluence of people and resources and common interests and goals,” says Harold McGee, a California-based food writer. “It’s not something that you could engineer in a business school.”

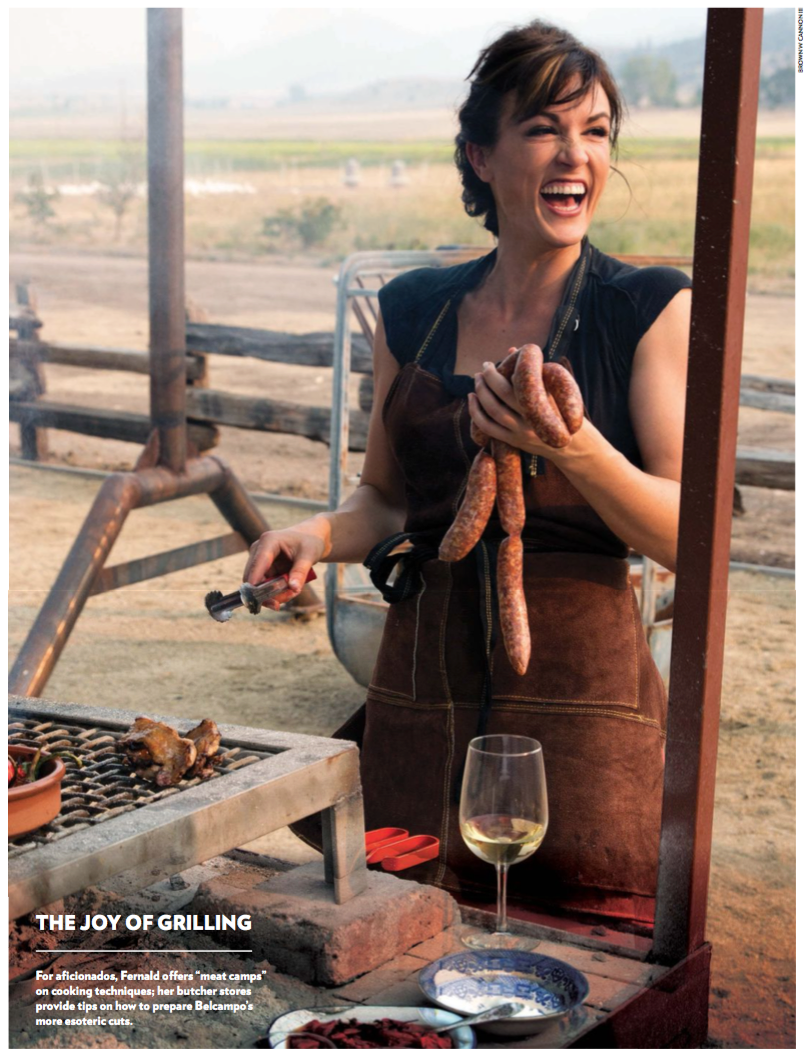

The company’s restaurants, including one where I ordered a juicy, perfectly cooked grass-fed burger with house-made ketchup for $15, have already started to turn a profit, Fernald reports. As the business has matured, Fernald is spending less time on the farm and more time developing products—including a recently launched line of animal fat-based cosmetics. “In business, by year five, if things aren’t pretty steady-state and turnkey, you’ve got a problem,” she explains. But she still spends around six weeks a year in Siskiyou County, to discuss farming and business decisions and lead “meat camps” where enthusiasts can spend a weekend learning advanced cooking techniques.

Fernald says she gives little thought to being a prominent woman in a male-dominated industry, but she acknowledges that once again, she is “an unusual figure.” When a magazine ran a profile with the headline “First Lady of Livestock,” Fernald thought about having the phrase emblazoned on a sash she could wear to work. Fernald’s unique combination of food, business, and people skills is key to her success in a difficult industry, says Belcampo farm manager Rodney Dowse. “She can finish her cookbook, do a photo shoot, talk to a class of fitness and yoga instructors about the health of meat, and be out on the farm, going out and moving cattle with us, and be in the board room talking about P&L [profit and loss], all in the course of a day.”

THE LONG GAME

As for any good West Coast entrepreneur, the big picture for Fernald involves not just selling a product but disrupting an industry. Whereas Americans once ate lots of different parts of lots of different animals, the corporate food industry has simplified our diets with factory-style production, and we’ve become used to bland, artificially cheap grain-fed hamburgers and boneless chicken breasts. The vast majority of meat consumed in the U.S. now comes from just three animals—cows, pigs, and chickens— with turkey a distant fourth, and everything else an asterisk.

Bucking the trend, Fernald launched Belcampo with 13 species: cows, sheep, pigs, goats, rabbits, chickens, turkeys, quail, geese, ducks, guinea fowl, partridges, and squab. Her shops feature photos of happy animals roaming on pasture. Helpful butchers explain how to cook not just ribeye steaks ($34.99 a pound), but cuts you might not have heard of, such as secreto (the brisket of a pig; $15.99 a pound). But despite seemingly doing everything right, Fernald has not been able to change enough customers’ habits fast enough to support her entire menagerie. She’s dropped rabbit, and, to her intense chagrin, goat: “It’s my daughter’s favorite. It broke my heart. … but I saved my company a lot of money.”

By being willing to be an outlier, Fernald has merged the personal and the professional, the passion-driven and the profitable, and made a 20-year-long dream a reality.

HOME COOKED

This year, Fernald released her first cookbook, Home Cooked, a beautiful celebration of both food and gathering around food. It’s arranged around the parts of the meal, and pitched to people who want to entertain with locally sourced ingredients and old-world flavors, but may be daunted by the seemingly endless list of simultaneous tasks involved. As I read it, I started to feel as though I really could have the ragu simmering on the stove while setting out a plate of artfully arranged sardines on crackers, serving Old Fashioneds and discussing heirloom tomato varieties. “Her book is very good at showing us how to relax, take it easy, do some things while people are there, enlist them, and keep things simple,” says Harold McGee, the California-based food writer—who is a fan.

Fernald says it’s part of her long-term plan to improve the meat Americans eat and restore food to the center of the social experience. “It’s a long game play for me,” she says. But it’s also charmingly personal, peppered with lines like “Carne cruda takes me to a really happy place.” In other words, it contains not just the what and the how of local sourcing and home cooking, but the why.

She has also proven savvy in capitalizing on food trends. Bone broth—a steaming concoction made by simmering cow bones for several hours—is increasingly recommended by many doctors and physical therapists, and has become one of her most popular items in her stores. Several people stopped in for a cup on a recent Sunday afternoon while I chatted with a butcher at Belcampo’s San Francisco store. For do-it-yourselfers, though, Home Cooked o ers a recipe, along with roasted bird broth and trotter broth. Calling bone the “über broth,” Fernald writes, “For a simple winter lunch, bone broth with a few beaten eggs whisked into it, finished with hot sauce and flaky salt, can’t be beat.”