NEVER GIVE IN

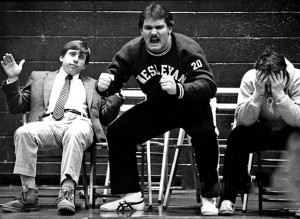

The young man gave his list to the college counselor; waited while she considered the names of universities where he planned on applying. He was a football player, a wrestler, a big kid with a meaty fistful of athletic accolades. His grades were decent, but his SATs weren’t stellar.

The young man gave his list to the college counselor; waited while she considered the names of universities where he planned on applying. He was a football player, a wrestler, a big kid with a meaty fistful of athletic accolades. His grades were decent, but his SATs weren’t stellar. Now, in the fall of 1978, he was a post-graduate at Loomis Chaffee, taking an extra year to prep for college, the first generation in his family to attend. He cleared his throat, fidgeted while the counselor pursed her lips and sighed.

She said the last name on his list. “Wesleyan University.”

“Let me tell you,” she said, not unkindly. “There are 22 students here who might apply to Wesleyan. You’d be Number 22 out of all of them to get in.”

The following September Mike Whalen’s parents moved their son into his Wesleyan dorm room on the cheek of Foss Hill. He’d spent the previous year transforming himself, commuting between the library and the weight room. Becoming the student-athlete the college counselor hadn’t seen. Had she dared him?

“Let’s just say,” he says now, the slightest grin sliding across his face, “It’s not a good idea to tell me what I can’t do.”

Mike Whalen ’83, head football coach and Frank V. Sica Athletic Director, with the sprawling Freeman Athletic Center under his command, is not all that different from the kid who entered Wesleyan in the fall of 1979, his friends will tell you.

Mike Whalen ’83, head football coach and Frank V. Sica Athletic Director, with the sprawling Freeman Athletic Center under his command, is not all that different from the kid who entered Wesleyan in the fall of 1979, his friends will tell you.

Says roommate and best pal Steve Sorkin ’83: “I still talk to him a couple times a week. The things that made him what he was when we were kids are still there—he’s working hard, he feels strongly about things, he loves, loves, loves competition.” The difference is, of course, that if he’s still proving the naysayers wrong, it’s on a larger scale.

Division Three recruiting is tough? Don’t tell Mike. Since his return in 2010, he’s brought dozens of highly-talented football players to campus.

Top coaching talent flees to Division One? Again, bad idea to tell Whalen, who’s hired a number of coaches with impressive résumés, including defensive coach Dan DiCenzo, who came with him from Williams, and Amanda Belichick ’07 (yes, of that Belichick ’75 coaching family) to lead women’s lacrosse.

Little Three Title? Not in 43 years. Good luck, Mike. Oh, wait. The 2013 season saw an unbeaten Wesleyan roll up the Little Three with a triumphant win at home against perennial tough guys Williams, losing only to Trinity in the last game of the year.

“It starts with passion,” Whalen says. “I’ve never looked at it like, ‘Oh, I have to get up and go to work.’ I have the good fortune of coming to a place I love to be. And I love a challenge.”

In 2009, the Cardinals were 3-5 on the gridiron. The last Little Three Championship had been in 1970. Other sports had up and down years, with some standout teams, but it’s safe to say nobody confused Wesleyan with its archrivals Williams and Amherst, or powerhouse Middlebury—in the most competitive Division III conference. A 2009 posting on collegeconfidential.com said: “Competitively, they range from fierce to ‘feh.’”

But change was in the air. Michael Roth ’78 had arrived as president in 2007, and he wanted to raise Wesleyan’s game in every area—from the classrooms to Andrus Field.

“Whatever we do at Wesleyan, we should strive to do well,” Roth says. We don’t have to win the most championships, but we have to have a high-quality program.”

Sports were not a big part of Roth’s Wesleyan experience. But he discerned the value of the athletic experience in a liberal education.

“Nearly a quarter of our students play a varsity sport, and they’re in tough competition. One thing they learn, that our other students don’t, or don’t as easily, is how to handle failure,” Roth says. “That’s a very important skill. Handling victory well is also important, and with Mike around, there’s a lot of that skill building!”

As he started to evaluate Wesleyan’s athletic program, and knowing that Athletic Director John Biddiscombe was thinking about retirement, Roth focused on Whalen, then ensconced at Williams for 15 years, with six years as a winning head football coach. He admired the guy he said embodied “classy ferocity,” and he understood it would take some wooing to lure the coach, then 38-10 with the Ephs, back to Middletown.

“I know Williams tried to keep him,” Roth says. “They could build new stadiums, but…“ He laughs. “They couldn’t compete with alma mater.”

Whalen remembers it slightly differently.

“What really resonated with me is that Michael Roth really believes in excellence. He said he doesn’t care whether it’s in a dance studio or a chemistry lab or a football field,” Whalen said. “When I heard those words come out of his mouth, I knew that this was the opportunity I wanted. To come here and rebuild the football program.”

Also important to Whalen was Wesleyan’s willingness to let him hire his own coaching staff. As close as it could come to a plug-and-play solution, the university allowed Whalen to bring not only Williams’ defensive assistant (and head wrestling coach) Dan DiCenzo, but also offensive coordinator Jack Siedlecki, (70-49 as head coach at Yale), and assistant Jeff McDonald (who’d racked up an impressive list of victories from UNH to Towson before joining Wes in 2008) along for the ride.

“A good story is that when I agreed to come back to Wesleyan, people said, ‘Is he crazy?’” Whalen stops for a minute, suppresses a grin. “When they heard that I was bringing these guys, the feedback switched to, ‘Can you believe the commitment that Wesleyan is making to football?’”

The news trickled down. It wasn’t just opposing NESCAC coaches eyeing the schedule differently. Potential recruits, their coaches and guidance counselors, all suddenly saw Wesleyan in a different light. Game-changer.

“It was no longer going to be just the Little Two,” Whalen says. “Wesleyan was going to enter the game.”

It helps to think of a successful coach having multiple personalities. There’s the on-the-field instructor; there’s the battlefield general creating plays and scouting opponents; there’s the inspirational leader; and there’s the evangelist: recruiting players and building the team.

It’s that piece—the recruiting—that is Whalen’s universally agreed upon secret sauce. He finds athletes of exceptional ability, in the classroom and on the field, and woos them with a combination of toughness, warmth, and high expectations.

“We start with a field of 1,500, maybe 2,000 potentials,” Whalen says. “We see a lot of camps, a lot of schools. But the first thing we’re looking for is academics. Once we get that piece down, what I’m looking for is leadership. Does he look me in the eye? When he’s going from one end of the field to the other, is he first in line, or last in line? And where is football in his priorities? It’s academics #1, but football has to be #1-A.”

For Whalen, recruiting is another form of competition.

“No matter what school you are at, the key to success is to figure out a way to market your institution,” he says. “Once you establish your recruiting pool, then comes the most challenging part, finding the group of student-athletes who are going to fit your system. Give me a group of guys who are always willing to put the needs of the team ahead of their own and we will win games.”

And he never forgets his own experience, choosing recruits who badly want to succeed. “He knows his recruits will exceed his expectations, not just meet them,” Sorkin says.

Two-sport athletes? He seeks them out especially. “There’s an incredible value to the two-sport experience,” he says. “It’s more than just being able to do two things; it’s stretching your abilities.”

And he’s careful to steer some kids if not directly away from Wesleyan, then into a detour—post-graduate work at prep school.

He says it’s because he has been there. As a senior at Enrico Fermi High School in Enfield, Conn., he was recruited by Division I teams in football. An injury made those offers disappear, and the PG year at Loomis was life-changing.

“I have steered a hundred—easily a hundred—kids to a PG year, and then heavily recruited them afterward,” Whalen says. “They may be really promising. But it takes some of them a while, particularly the guys, to mature academically, athletically, emotionally. Another year at the right place does it.”

There’s another reason why Whalen gets through to kids as a recruiter, his wife, Karen, says: “He treats these young men like they are, or might be, his sons. That continues on to when they’re players, but it’s the first thing.“

On the sidelines of most games—maybe selling sweatshirts, if it’s a home game, or in the stands—you’ll see a tall, blonde woman with a wry smile and a practical demeanor. She may be one of the few people at Wesleyan who doesn’t call Whalen “Coach.”

He’s been “Mike” to Karen Whalen since the late 1980s, when they met at Lafayette College. He was an assistant coach; she was assistant athletic director. Karen liked Mike’s “unexpected” sense of humor and his fierce dedication to the job. And as an athletic administrator, she knew the ins and outs and daily demands of that job. Mike liked that. “We clicked,” she says.

Karen, now director of communications and operations for University Relations, often, perhaps unconsciously, uses the word “team,” in describing their family.

They’ve raised their two boys—Jake and Luke, young men now—in Williamstown and Middletown, and it’s always been a joint venture, Karen says. Mike’s dad style is similar to the way he coaches.

“The thing about Mike as a parent is this,” she says. “He expects our kids to be accountable. If they say they’re going to do something, if they commit to something, they do it. He’s actually a softie—the good cop—most of the time, but he has high expectations. And everybody knows that.”

That thing about a competitive streak? Oh, yeah. Karen tells of a time when the Whalens went bowling—a weekly social outing for them, downtime with friends—and she cut open a blister on her hand. “It really hurt, and I wasn’t up for more.” Mike raised an eyebrow. Come on, Team Whalen.

“I bowled,” she says. “No way I’d let down our side.”

As an undergraduate, the kid who wasn’t cut out for Wesleyan continued to prove the naysayers wrong. A sociology and education major who earned a teaching certificate along with his BA, Whalen was a leader on the football team, and the only four-time New England wrestling champion. And it wasn’t all sports and study. A brother at DKE, house manager at Downey House (then a pub for students), and a roadie for Wesleyan band Dr. Mezzi Fights Infection, he was also “a fun person, without a doubt,” according to Sorkin.

After his BA, and harboring dreams of professional football, Whalen thought he might teach a bit while working out, and go out for the U.S.F.L., then an attention‑getting nascent league that had offered him a spot during his senior year. But an assistant job at Wesleyan convinced him that he was more excited about watching game film and working with players than actually going out on the field.

A master’s at Springfield College (where he was an assistant coach) was quickly followed by a year at the University of Pennsylvania, where the Quakers notched the 1986 Ivy League title. Ivy League coaching turned into Patriot (later Colonial) League coaching at Lafayette, with league titles in 1988 and 1989. At Colgate, he was associate head coach and offensive line coach. It was in Purple Valley where he honed his head coaching skills, in wrestling and later, in football, where he led Williams to numerous victories, including the sixth perfect season in Ephs football history in 2006. He was named the NESCAC Coach of the Year that year, and selected as a finalist for the 2006 Liberty Mutual Coach of the Year Award, the only Division III coach among 16 finalists.

And then, in 2009 a call came for Williams’ Coach Whalen from Wesleyan’s President Roth. At first it was just about advising his alma mater on hiring a new coach. After a few such conversations, though, Whalen realized that he was, in fact, being recruited himself. When he made the decision to move Karen, their sons, and himself to Middletown, it seemed both unreal and perfectly fitting, he recalls. And the first call he got, the night the news broke, was from another Wesleyan alum, New England Patriots Coach Bill Belichick ’75.

“Welcome back from the dark side,” he told Whalen.

Whalen’s arrival at Wesleyan was hailed as a new era in Cardinal sports, but there were skeptics. However, none of them were on the team. “It was the energy, the confidence, he brought to the team,” said Joe Giaimo ’11, who came to Wesleyan as a quarterback and is now an assistant coach for Whalen and assistant director of the Wesleyan Fund. “If people thought we couldn’t do it, he immediately convinced us that we could, that we would. And we did.”

It’s not all about football. At Wesleyan, the guy with the whistle is also the athletic director, managing the work of the coaches who helm 27 varsity teams and running the Freeman Athletic Center and all the sports, fitness, and athletic programs it supports.

“Makes for long days. Definitely, I’m lucky to have great people here who coach, take care of the athletes, do the work of the administration,” Whalen says. “I enjoy talking to people, figuring out how to approach a problem. Of course, whenever you’re in charge of something, you have to know you’re not going to make everybody happy all the time.”

He was eager to accept the dual job because it gave him a chance to remake athletics at Wesleyan on a larger scale than football, and make a lasting difference in the life of the university. His goal is to reposition Wesleyan as an athletic leader among its peer schools. That doesn’t necessarily mean racking up NESCAC championships left and right. Whalen sees it as a process, ensuring strength over time, establishing solid programs through improved recruitment; better intramural communications, and more engaged alumni.

“We’ve got some great alumni support, not just through the (Athletic) Council, but through folks who come back here and want to support their teams, or want to help Wesleyan but do it through athletics. It meant something to them when they were here as athletes. For some people, that’s the most important connection they have with the university,”

Along with a robust mentoring program that pairs alumni athletes with current members of their teams and dedicated fundraising, the assistance from former Cardinals often comes in the form of a phone call—a little friendly coaching advice. “All. The. Time,” Whalen laughs. “And I welcome it. Sure, absolutely. These are their teams.”

Women’s athletics are also on the top of Whalen’s list. “It’s important that female athletes have every bit as much of a chance at success as the guys, and we make that happen here,” he says. Whalen has tapped into the support of the pioneering early classes of women at Wesleyan to energize women’s sports, organizing golf tournaments and mentoring events featuring Cardinal women of the 1970s and ’80s.

November 2, 2013, was a gorgeous day; a day for football under a blazingly blue sky, and a little warm for fall, with barely a breeze. Tailgating had started early at the foot of Foss as alumni, parents, and students gathered for the penultimate game of the season, undefeated Wesleyan hosting Williams in the bout that would determine the Little Three title. Cardinal Pride was everywhere, and amid the party atmosphere there was a sense that this could be the moment when everything changes.

Mike Whalen wasn’t so sure, he’d say later. “I thought it would be another year,” he says. “One more recruiting class. But when we beat Amherst, (two weeks earlier) in their new stadium, on their Homecoming, I thought, maybe, maybe… But I wasn’t counting on anything. People thought, okay, it’s Williams, so probably not. Maybe that’s all it took.”

Three hours later, streaks and records were broken and things had changed, as Mike Whalen’s guys fought back a seriously determined Williams squad to take the title for the first time in 43 years. The South College bells clanged joyously. Spectators rushed the field. Whalen handed the game ball to a grinning Michael Roth. The TV cameras caught a jubilant coach, surrounded by his players in a swarm of red and black and raising a fist in the air.

“This guy,” he yelled hoarsely, hugging Roth. “He’s the reason I’m here, and I’m the reason you’re here.” The team erupted in the fight song. “Never give in… .”

“We did it,” he was heard saying as he left the field. “You did it. They said we couldn’t, and we did.”