Redrawing New York City’s Skyline

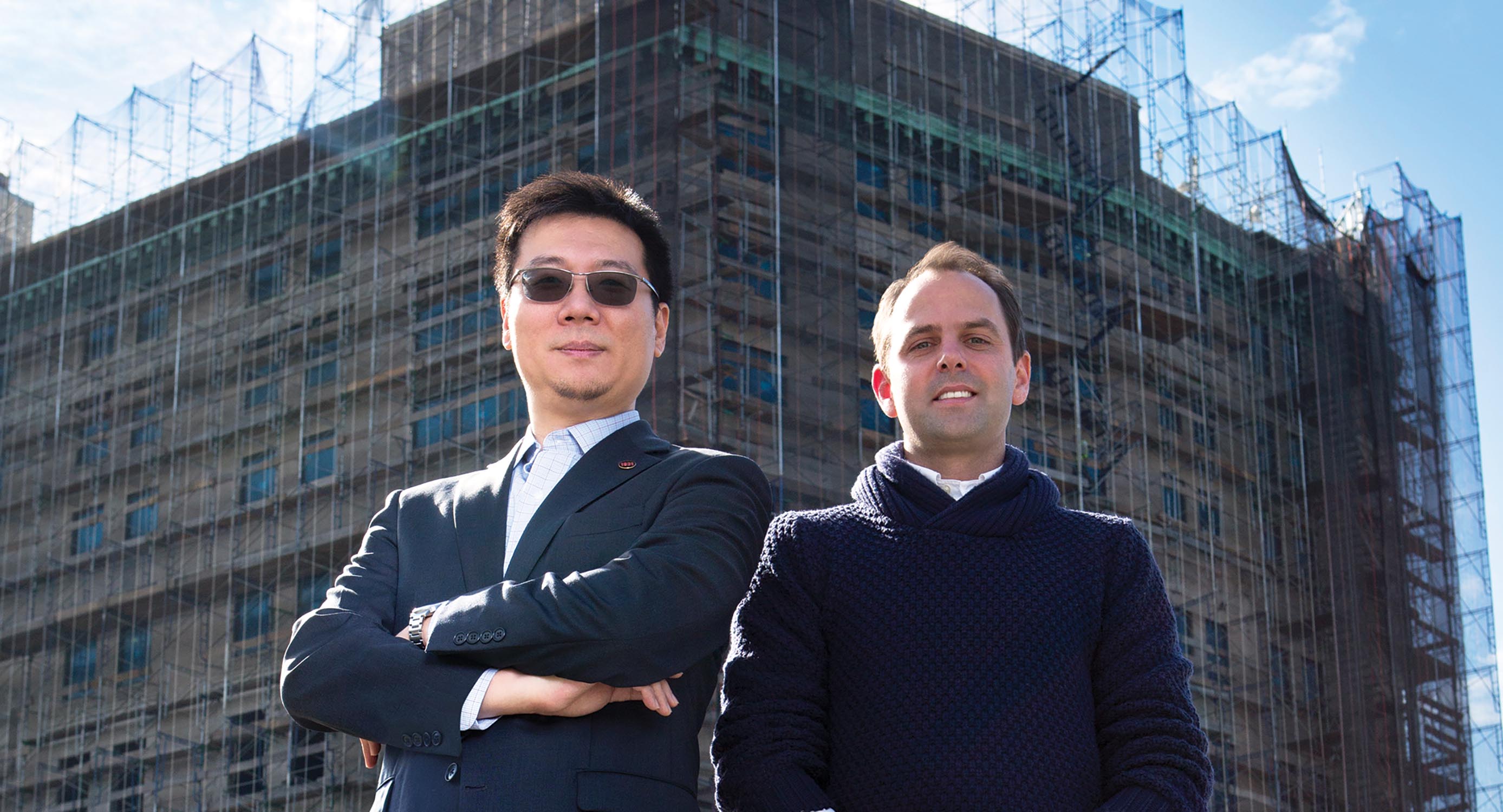

Years removed from their Wesleyan friendship, two alumni reconnect in monumental fashion. Photo by: Robert Adam Mayer

After a few hours touring New York City with Benson Gillespie ’04 and Kwei Chang ’05, you’re likely to end up with a stiff neck from looking upward, as well as a new appreciation of the city’s skyline, its structures, and the challenges that construction presents.

The two friends, architecture majors as undergrads, are now frequent collaborators on projects throughout the Big Apple, using their common background to enhance both process and product for new construction and restored buildings. Gillespie, who arrived at Wesleyan with astronomy on his mind (the Van Vleck Observatory was a great draw), had his sights shifted from the stars to the skyline when a click of his mouse during registration nailed him a place in a highly coveted sculpture class.

“That class took over my life,” he recalls. “I spent all my time in the studio.” The following semester he took an architectural class with Martha Añez and knew he’d found his focus.

Chang, who calls himself “a very lucky Freeman Asian Scholar from Taiwan,” arrived at Wesleyan already placing out of the 100-level physics courses and determined to be an electrical engineer. Then, in his sophomore year, while visiting a friend’s dorm room, he saw a few architectural models from one of Añez’s classes.

“I said to myself, ‘This is amazing! These models are something I could take home, that my friends and family could enjoy.’ While theoretical physics was intriguing, architecture allowed a synergy between physics, engineering, and creativity that fascinated me.”

Only a year apart, in the same program with Añez as their mentor, the two became friends. Each went their own way to graduate school—Gillespie to Rice University, Chang to University of Pennsylvania—and after a while, both reconnected in New York City.

Gillespie recalls, “I began to work in a façade consulting and inspection firm under someone who really excelled in his specialty. When the opportunity arose to follow him in building a start-up, I jumped at the chance. Now my former boss is one of my partners and our firm, Surface Design Group, has been growing ever since.”

Chang completed his graduate study in both architecture and real estate development, and started working, at this nexus, as an architect on city-scale projects for an international architecture firm before transitioning into real estate development. The evolution was logical, he says.

“Wesleyan prepared me to easily straddle two cultures: I have the Asian heritage and the Western education.”

He explains: “Many architects are very passionate about design, about quality, and about delivering something special for society and the world. However, some believe that developers—unlike themselves—are primarily budget-driven, so they think that they cannot be on the same team.

“But this is again about cultural translation: I’m trained as an architect but also know how developers crunch the numbers. The qualitative and quantitative skills in my background allow me to deliver most buildings on time and within budget. The façade is such an important component that it is critical to find the right person to provide quality for the client, occupants, and neighborhood. As I began assembling our teams, I realized that Benson and his firm would be perfect for some of our very challenging projects. That’s how we started a conversation about working together.”

For those considering a trip to the city, the duo note that they’d be pleased to guide you on a tour of their ongoing projects. They agree that one of their most interesting collaborations currently is One Prospect Park West in Brooklyn, with Sugar Hill Capital Partners. There, at the corner of Grand Army Plaza, right across from the arches and statue of the soldier on horseback, you’ll find their building, still cloaked in temporary scaffolding, almost chrysalis-like. One hundred and fifty feet, or 10 stories, high, it is wider than it is tall, occupying the entire city block.

Gazing at it from across the street the two architects provide an introduction to this once-and-future grand dame. Chang starts with the résumé: “It was once the headquarters for the Knights of Columbus, back in the 1920s. In the late 1950s, it was purchased by another Catholic group and was renamed as Madonna Resident, and in the 1990s it became a hospital and senior living facility, but was vacant when purchased. Although it’s not designated as a landmark, we decided to restore it as if it were one.”

Gazing at it from across the street the two architects provide an introduction to this once-and-future grand dame. Chang starts with the résumé: “It was once the headquarters for the Knights of Columbus, back in the 1920s. In the late 1950s, it was purchased by another Catholic group and was renamed as Madonna Resident, and in the 1990s it became a hospital and senior living facility, but was vacant when purchased. Although it’s not designated as a landmark, we decided to restore it as if it were one.”

“It’s a beautiful building. I don’t know how it got exempted, but we’re still treating it as a landmark,” Gillespie agrees. “We’re actually restoring a substantial portion of the façade—with the exception of the rear elevation, which is being completely demolished and erected anew, essentially all glass.”

While the upper floors rise above the roofs of its shorter neighbors, the first few are mere feet from the buildings next to it. The proximity gives one pause: How would it be possible to take down this entire outside wall with neighbors living arm-lengths away from this major demolition?

“How did we do it? Very carefully,” says Chang.

“Construction is complicated in the city,” Gillespie concurs. “You don’t have a lot of room to bring in heavy equipment; the material we take down has to go out through the building, essentially in wheelbarrows.”

Standing on one of those top six floors as the sun begins to fall low behind the New York skyline, the view can seem well worth a Sisyphean tear-down task. Join the duo on a walk through the inside shell and Chang will point out struts—huge V-shaped pillars built to support the floor below what was once an indoor pool—and note the fact that each of the floors had to be raised about a foot, in order for the windows to fall at the proper level for the people who will live within these apartments.

“Otherwise no one would be able to see out the windows,” he explains. “They were built to provide light, but not for people to look out.”

“We run into a lot of unforeseen situations when we’re working with existing buildings,” says Gillespie. “This building has been particularly full of them. In iconic buildings like this, people have done renovations but didn’t document it. With new construction, if the drawings say the floor slab is here, the floor slab is there.”

“The most recent drawings we found were from the ’50s, crumbling blueprints that we scanned,” Chang says. “Still, 40 percent of the building was not documented. Then we 3D laser–scanned the entire building to understand exactly where all of the façade, all of the columns actually are, because structures can shift over a century.”

Back outside on the street, Gillespie points out a number of large medallions on the façade between windows. Originally of terra-cotta, they were crumbling from a century of weather and city grit. Unwilling to lose those grace notes, Gillespie’s firm made molds, recasting the designs in more rugged material. Chang gestures to one whole corner of the building, from sidewalk to rooftop. “In an earlier era, they’d bricked up all those windows that had overlooked the park to put in what we call ‘the million-dollar elevator,’” he says. “We’re taking them out now, opening up the view.”

It’s a short trip by Uber to Battery Park, where the duo point across the Hudson River to the tallest building on the other shore, 99 Hudson Street in Jersey City. Still a work in progress, its windows covered with a blue film during construction, this project is one that Chang and his developing firm show with pride.

“People joke that the best way to view the skyline of New York City is from outside the city,” he notes, adding that those who will live at 99 Hudson Street will have a mere 10-minute commute to New York City by ferry.

The next stop on their itinerary lands a visitor in the southern end of Central Park, where, if one clambers to the top of a small rocky ledge, 217 West 57th Street is visible, rising above the trees. Over 1,000 feet tall already, it will be the tallest residential building in North America, and it’s a project that burnishes the name of Gillespie’s firm. Slated to be completed in 2023, the bottom floors will offer retail locations (already dubbed “the Nordstrom Building”) with the upper levels slated for condos.

For these structures, the two note that developers and architects must interpret building codes that are as complex and arcane as tax codes (or more so) and obtain all necessary permits. The height limits, for instance, are calculated in relation to the square footage of the building’s footprint. Also, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) will need to weigh in.

Gillespie mentions that it is not uncommon for developers who plan a 1,000-foot-tall construction to find that they must readjust the height to receive FAA approval.

“It’s all about proximity to airports,” he explains. “You have to be under a certain height within a radius. In Queens, we’re close to LaGuardia.” He nods to Chang. “You have to deal with that in Newark, too.”

Walking toward Grand Central, the two almost pass a construction project but stop for an impromptu discussion of its use of slumped glass—glass that has been heated and placed over a mold to shape it—and its possible application in an upcoming project.

“I think we work together well,” observes Gillespie, “and a lot of it is our common background. In this city, with this dynamic workforce, you find yourself constantly adjusting to a multitude of personalities, work ethics, and even generational differences. I don’t know if I’d find it true for all alumni, but I know that trust is a solid base in our collaborations. There’s a synergy between us that we cherish.”

“Real estate development is a complex imagination game with numbers,” Chang acknowledges. “And I cannot guarantee that I can know everything—but our Wesleyan education has provided us with the confidence that we’ll find ways to effectively approach challenges. I like to surround myself with all these smart people who specialize in different areas, and then we work as a team to tackle the question. Benson and I have the same background in our education at Wesleyan. If we run into a problem at a job, I find that when I’m thinking how to solve it, Benson is thinking about it the same way that I am.”

Kwei Chang ’05 is a director in the real estate development firm China Overseas American, located in New York City. He has managed design projects across Asia, Europe, and North America, as well as headed development projects in the states of New York and New Jersey. He is a registered architect in the State of New York, a LEED Accredited Professional, and a member of American Institute of Architects with a master of architecture degree and a real estate certification from the University of Pennsylvania.

Benson Gillespie ’04is a partner in the façade consulting firm Surface Design Group, located in New York City. With over a decade of experience as both a technical façade designer subsequently a façade consultant, he was worked on a wide range of projects that vary in both scale and complexity, with a multitude of façade types. He is a registered architect in the State of New York, holds a master’s in architecture from Rice University and has been an invited architectural panelist at various Conferences and Universities both in New York and Houston.