Bill Shapiro ’87 and What We Keep

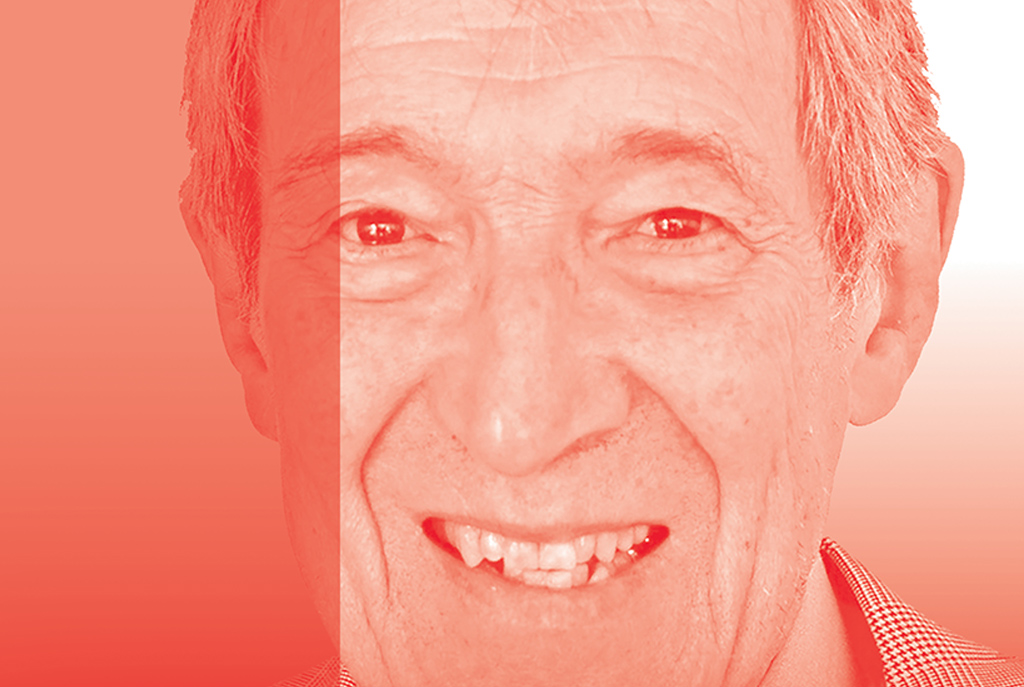

For their new book, Bill Shapiro ’87 and Naomi Wax interviewed hundreds of people about the single object that brings the most meaning to their lives. Here, they pose that question to Joss Whedon ’87, Amanda Palmer ’98, Professor Andrew Szegedy-Maszak (pictured), and other members of the Wesleyan community.

Three years ago, my coauthor, Naomi Wax, and I began to talk to people about the single object in their life that carries the most emotional significance. We interviewed hundreds of people from every state, circumstance, and vocation imaginable, from a former counterfeiter to a cloistered nun, from Ta-Nehisi Coates to an Alaskan bush pilot, from Melinda Gates to a man imprisoned for 34 years. Even a few Wes alums. In the end, we gathered these stories into a book called What We Keep: 150 People Share the One Object that Brings Them Joy, Magic, and Meaning, from which some of the interviews that follow were taken.

Everyone asks us two things: What’s the weirdest object you came across (a bottle opener owned by a drug-dealing grandma? A Syrian banknote pierced by shrapnel?), and how did you get the idea for the book?

A lot of people like the notion that ideas come from strange places and at unexpected times, the proverbial zap of lightning from out of the blue.

For us, it was less about a burst of brilliance, and more about pattern recognition. After Superstorm Sandy hit Brooklyn in 2012 and swamped a nearby neighborhood, we watched as residents said goodbye to their beloved belongings. Two years later, a photograph crossed my screen that I could not take my eyes off: a Syrian refugee fleeing her home, carrying only her child and a small burlap sack. I remember wondering what was in that sack: Did she bring something to remind herself of the home she might never lay eyes on again? At the same time, we’ve all seen CDs and photographs move off our shelves and into the cloud, and our kids’ messages fade into the Snapchat ether. As Naomi and I talked about how these changes might transform humans’ relationship to physical objects, our thinking began to coalesce.

If we had a “lightning” moment, it came at a yard sale in rural New York when Naomi plucked a locket from a bin of odds and ends. It was dated 1911 and, inside, the inscription read “My love forever.” The locket was so delicate, so personal, that it was hard to fathom how it had ended up here, at the end of a driveway, for sale to strangers. It struck us that, over the years, the story that had once made that locket so special to someone had become untethered from the object itself. Driving away from the yard sale, we came to focus on the importance of the stories that bind us, at least for a while, to the objects that give our lives meaning. And we set out to collect them.

***

Before the Nazis came to power, my family lived a very privileged life in Hungary. Their home had a library with first editions, and there were paintings—masterpieces—on the walls, a beautiful little collection of Dürer woodcuts, and this odd, battered, wonderful statue that my grandmother had picked up in Paris. It’s old—maybe from the 16th century—and has been in my family for at least 80 years. For me, it’s kind of totemic and carries fragments of a lost life.

Before the Nazis came to power, my family lived a very privileged life in Hungary. Their home had a library with first editions, and there were paintings—masterpieces—on the walls, a beautiful little collection of Dürer woodcuts, and this odd, battered, wonderful statue that my grandmother had picked up in Paris. It’s old—maybe from the 16th century—and has been in my family for at least 80 years. For me, it’s kind of totemic and carries fragments of a lost life.

My family escaped the fate of many Hungarian Jews only because there was an honorable SS officer who promised that if they signed over all of their possessions, he would guarantee them safe passage to Portugal. They did and he did.

We’re still not sure how they managed to keep the statue but it was part of the household when I was a kid. I grew up in an old house in D.C. with my parents, grandparents, and an aunt—and the statue stood atop a bookcase in the corner of a dark living room. My grandmother had put a piece of maroon velvet behind the statue, which gave it the feeling of a shrine. There were a few remnants of the old grand life but very few, the rest having been seized and dispersed.

My parents had a lot of Hungarian friends who spent time lamenting everything they’d lost and the gilded age that they’d had to leave, but what I realized as a kid was that my family was far more vocal about how lucky they’d been, how blessed. My parents made it clear that we had so much to be grateful for. And that, I think, is one of the most valuable things they gave me; an inheritance, of sorts.

For me, the statue conveys that: This object, this plucky little piece of wood, is a survivor. Today, it’s in my house, and while it’s beat up, certainly, it still has traces of the original paint, and it’s still beautiful. I find that very encouraging.

—Andrew Szegedy-Maszak, Jane A. Seney Professor of Greek, has been on the faculty of Wesleyan University for 44 years; Middletown, Connecticut.

***

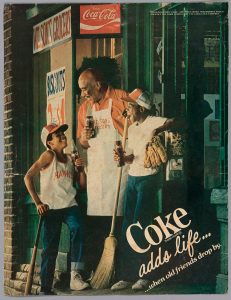

When I was A teenager, the walls of my room had posters of Public Enemy and The Who—and this old Coca-Cola advertisement from Ebony magazine.

When I was A teenager, the walls of my room had posters of Public Enemy and The Who—and this old Coca-Cola advertisement from Ebony magazine.

The shopkeeper in the picture is my grandfather, Raphael Angelo McIver. All the adults called him Ray, but to my brother and me, he was Grandpa Mac. He played Go Fish with us, talked to us more than the other adults did, and he meant the world to me. He was a teacher, a writer, a poet, and, mostly, an actor. He loved performing Shakespeare—I remember him coming to my hockey games and yelling Shakespeare from the stands: “Let slip the dogs of war!” But being African American in the Deep South, he mostly performed on the radio.

And he called me “pal,” which I adored.

I was only nine when he died, and his death had such an impact on me. I just wanted to hold on to a piece of him. The two boys in the Coca-Cola ad were smiling and laughing, and they reminded me of me and my brother. So I put the Coke ad on my wall. I didn’t apply care to the edges—I used thumbtacks, masking tape, what have you, to keep it there as long as possible.

In the years after Wesleyan, I led a semi-nomadic life and some of the things that I carried with me over the years I can no longer find, some no longer exist. But this is different.

I began working at the African American Museum of History and Culture in 2010, and when I was asked to curate the Sweet Home Cafe section—about the intersection of food and African American culture—the Coca-Cola ad was the first thing I thought of. It was perfect for the exhibit, and it would allow me to share Grandpa Mac with the rest of the world. My family has seen that ad a million times, but the first time we saw it at the museum, under glass, it brought tears to our eyes.

—Kevin Strait ’97, museum curator, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture; Washington, D.C.

***

“My strat” sounds cooler than it is because it isn’t a Stradivarius or Stratocaster. It’s my straw hat—a boater, like they had in the ’20s. We had to wear them at Winchester, my boarding school in England, along with a jacket and tie. We couldn’t be bothered to say “straw hat.” Just “strat.”

“My strat” sounds cooler than it is because it isn’t a Stradivarius or Stratocaster. It’s my straw hat—a boater, like they had in the ’20s. We had to wear them at Winchester, my boarding school in England, along with a jacket and tie. We couldn’t be bothered to say “straw hat.” Just “strat.”

We’d treat our strats like shit, and at some point the housemaster would say, “You’re holding a piece of straw, and that won’t do.” I got a new one my senior year, which is the one I keep on the wall of my bedroom, where you’d hardly notice it.

I was 15 when my mom and stepdad, who were both teachers, left New York for a sabbatical in England. They didn’t believe there were actual schools in California, where my dad lived; they thought everyone out there was making movies and fighting Indians. Winchester had the best academic rep in England—and I had no business being there.

My strat brings up the most delicious Dickensian memories: All of the classrooms at Winchester were stone, all the kids had fingerless gloves, and everyone’s suits were shabby. But even sullen teenager me would look around and say, “This is the most beautiful place and these are the best teachers in the world.” There’s some guilt at how much work I didn’t do and how much I didn’t live up to what I wanted to be there; a lot of the things I was going through didn’t have acronyms yet, and if it wasn’t English or history, I almost physically wasn’t able to study. But the teachers were phenomenal, and although I was originally supposed to go back to New York after a year, I decided to stay. I stayed for the education … and then I abused it. I basically majored in dropping acid.

So while my strat really serves no purpose —it’s not like I’m sporting it when I go bar- hopping—it’s this absolute tangible reminder that my life was once that weird and that old-fashioned, that I lived through this crazy experience of being dropped into a hermetically sealed time capsule, a 600-year-old, all-male boarding school in England. There’s a certain amount of pride—well, not exactly pride, more like ownership—and a little delight at having been part of something that shouldn’t have existed in the modern era. I’m not a collector of things. I’ve walked away from a lot and I have thrown away a lot, including a perfectly healthy relationship. So I’m real good at moving on. But the strat is different. There was never a time I didn’t want my strat. There was never a moment when I was like, “I’m over this.” I was at Winchester until I was 18, but, in a way, I never came back.

It does nicely on the wall.

—Joss Whedon ’87, writer, director, activist, creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer; Los Angeles, California.

***

This is the first dress I bought for my daughter. She was four years old and she had been begging me for a dress for over a year when I finally gave in and bought her this hot-pink number. She wore it for the first time on Christmas Eve, and she entertained all the aunts and grandmas with her dance around the living room, so proud of how the skirt poufed out when she twirled. Her hair was still cut short, and we were still calling her by her boy name, but the writing was on the wall. There was no going back, not after this dress.

This is the first dress I bought for my daughter. She was four years old and she had been begging me for a dress for over a year when I finally gave in and bought her this hot-pink number. She wore it for the first time on Christmas Eve, and she entertained all the aunts and grandmas with her dance around the living room, so proud of how the skirt poufed out when she twirled. Her hair was still cut short, and we were still calling her by her boy name, but the writing was on the wall. There was no going back, not after this dress.

Five years on, each time I spot it hanging in the back of the closet, I’m still overpowered by the emotions I felt that Christmas Eve: sorrow at the impending loss of my son, guilt that I hadn’t bought the dress sooner, terror over what was to come, and more than anything else, joy: I had never seen my child so happy.

—Marlo Mack ’95, producer, How to Be a Girl (podcast); Seattle, Washington.

***

This is the first earring I ever designed. Now I use a 3D printer to make them, but at the time I had just picked up some craft wire in a jewelry store on Main Street, along with a pair of pliers and some other cheap tools. I was a junior then, and I’d been looking at jewelry designs in magazines and thinking I should start making my own work.

This is the first earring I ever designed. Now I use a 3D printer to make them, but at the time I had just picked up some craft wire in a jewelry store on Main Street, along with a pair of pliers and some other cheap tools. I was a junior then, and I’d been looking at jewelry designs in magazines and thinking I should start making my own work.

When I look at this wire now, 16 years later, so many things come to mind. It was the beginning of a lot of reconciliation about how my life fit together. That was around the time I came out. Speaking my truth and coming out felt like the end of something, the end of how my parents saw me and how I saw myself. But I was able to go from that difficult time to actually being able to open up a new way to see myself—and a new way for my parents to see me. Sometimes we get stuck and think, This is who I am, this is where it ends, but things are more continuous than that.

I remember I spent hours working on the wire in my dorm room and I kept coming back to this circular design, this continuous line where you can’t tell where it begins or ends. It’s a simple design but it says so much to me. About transformation, continuity, about new beginnings.

—Xiomara Lorenzo ’05, director, digital experience strategy, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts; owner, Xiomara Lorenzo Designs; Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts.

***

I’ve had a crazy life with a lot of ups and downs, and I always met a pregnancy stick with fear and loathing. But when I got to the time of my life when I was ready to have a child, I was overjoyed and found myself looking at the stick over and over. It became a beautiful object.

I’ve had a crazy life with a lot of ups and downs, and I always met a pregnancy stick with fear and loathing. But when I got to the time of my life when I was ready to have a child, I was overjoyed and found myself looking at the stick over and over. It became a beautiful object.

I thought I’d save it. I thought I’d give it to my child and tell them that it was the start of our relationship. So I put the stick in an envelope with the name I was hoping to give the child if it was a girl. I taped it up on my apartment wall.

I’m a hardcore feminist, and the culture didn’t really teach me much about motherhood—and nothing at all about the marriage of motherhood and musicianhood. Role models were few and far between; people just drop out. So I was scared, and I spent long, hard nights trying to figure out how to be a rock star and a mother. I’ve made it my personal mission not to drop out, and to include motherhood and my child in my art. And it’s been totally fucking awesome. I highly recommend it.

—Amanda Palmer ’98, songwriter and author; Woodstock, New York.

**

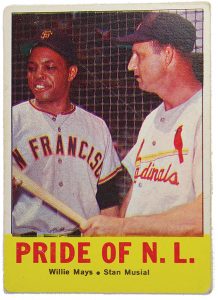

My brother decked me once in a fight over some pancakes but mostly we had a good, competitive relationship. We both collected baseball cards, but where my brother tracked his cards, had full collections from each year, I was two-and-a-half years younger and just happy to have a card with cool colors on it. So when I somehow got a 1963 card with Willie Mays and Stan Musial but wouldn’t trade with him, it stuck in his craw. It was a unique card—it said “Pride of N.L.”—and he was pissed that I had it, didn’t value it, and wasn’t going to take care of it. He put a lot of deals on the table, offering me a mess of cards for it, cards and money, he’d set the table 20 times. But I wasn’t giving it up.

My brother decked me once in a fight over some pancakes but mostly we had a good, competitive relationship. We both collected baseball cards, but where my brother tracked his cards, had full collections from each year, I was two-and-a-half years younger and just happy to have a card with cool colors on it. So when I somehow got a 1963 card with Willie Mays and Stan Musial but wouldn’t trade with him, it stuck in his craw. It was a unique card—it said “Pride of N.L.”—and he was pissed that I had it, didn’t value it, and wasn’t going to take care of it. He put a lot of deals on the table, offering me a mess of cards for it, cards and money, he’d set the table 20 times. But I wasn’t giving it up.

Then he got a knife. It was plastic, like a prop from a movie set, silver blade, leatherish handle, really cool. He did kung fu moves with it, and it just looked like the kind of thing that gave you adventures. I broke down and traded the card for it. I immediately took the knife outside to show my friends and goof around. I can’t remember exactly what happened but the knife flew into this big wall of ivy. It was gone. I was devastated and tried to talk it through with my brother: I only had it for a few hours, it isn’t fair, I want my card back. That’s where it ended.

Until my 40th birthday. My entire family gets together and in the middle of opening presents, my brother hands me a small package; it’s a stack of cards, each in a plastic sleeve. Lovely, I think, and start flipping through them. And there it is: Pride of N.L.

I don’t know why, exactly, but it made me cry. It’s like we form these attachments to objects and they become totems of our past. There were a lot of emotions wrapped up in it: Envy. Jealousy. The older kid and the younger kid. It wasn’t just a card.

—Anthony Weintraub ’87, filmmaker; cowriter, coproducer, Bel Canto (Screen Media Films, 2018); New York, New York.

***

Bill Shapiro ’87 is the former editor-in-chief of LIFE magazine. Naomi Wax works for the Ford Foundation. This article includes excerpts from their new book, What We Keep (Running Press, 2018). Excerpts reprinted with permission.