A Line in the Sand, by John F. Ross ’81

Turning a phrase well is often celebrated in our culture, as is the ability of a painter to capture an expression or a filmmaker to vouchsafe an emotion. And for good reason: it requires the greatest leaps of imagination and bursts of creativity to translate words, pigments, and pixels into things that resonant deeply with the human experience. Less well celebrated, although no less beautiful and profound, is when scientists turn a lifeless-seeming bank of numbers into something that challenges our deepest held assumptions.

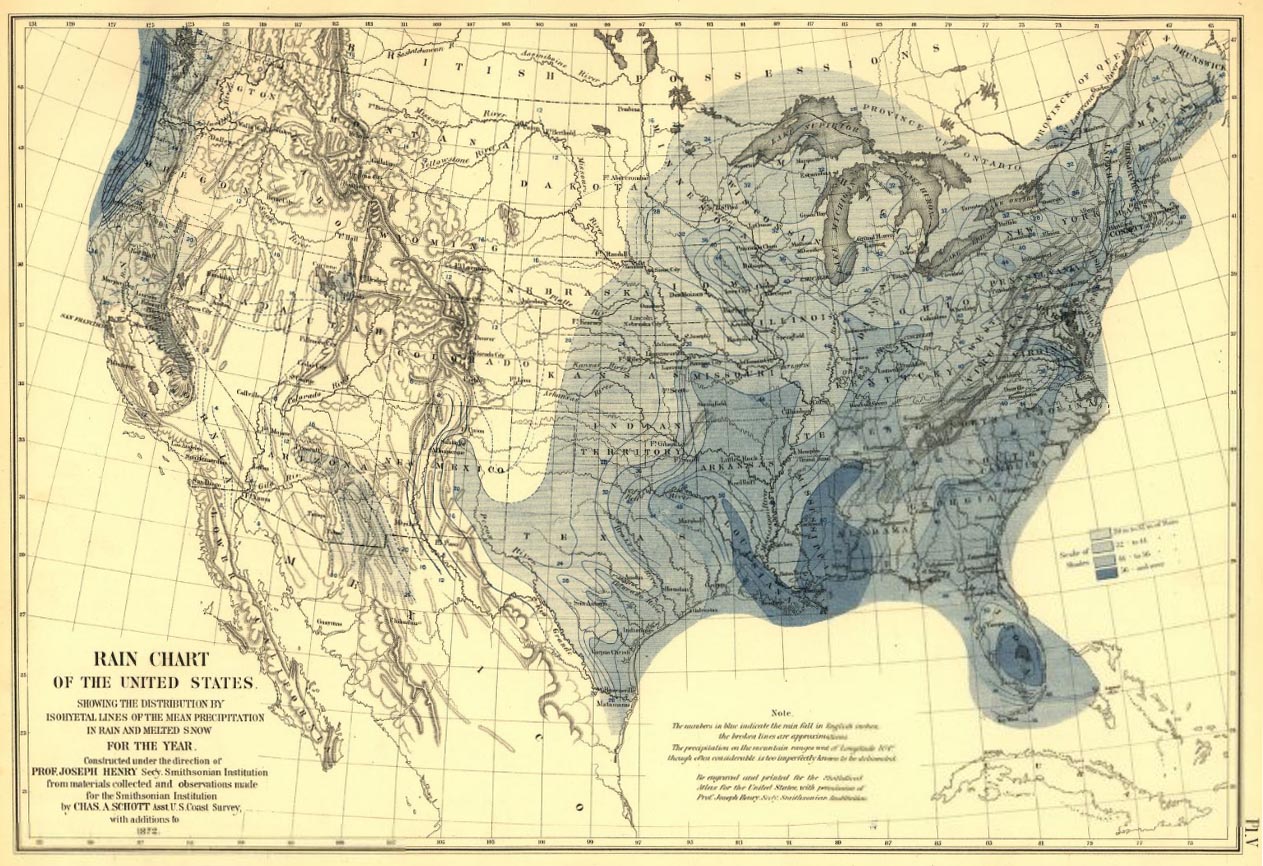

Scientist and explorer John Wesley Powell did just that in April 1877. He drew a line on a map bisecting the continental United States, and presented it to the nation’s most influential graybeards at the annual gathering of the National Academy of Sciences. That line would spark a heated national dialogue, and arguably become the most important and enduring line drawn in the sand in American history.

The Academy members knew Powell, as did most of America, as the one-armed Civil War veteran who led a courageous dash down the Colorado River in small rowboats through the unexplored and as-yet-uncomprehended Grand Canyon. As a geologist, he had been the first to rigorously examine the extraordinary swath of Earth history revealed in the strata of the Canyon’s mile-high walls.

The line he drew on the map approximated the 100th meridian, beginning in central Texas and rising up through Kansas, east of Nebraska, and through Minnesota and the Dakotas, to Canada. Powell had created an isohyet, a line connecting areas that experience equal volumes of annual rainfall, essentially separating the arid West from the verdant East. The relatively humid lands to the east experienced 20 or more inches of annual rainfall; the arid lands to the west received less, excepting some narrow strips on the Pacific Coast. He selected 20 inches because conventional agriculture needs at least that much moisture annually unless supplemented by irrigation. The implications of his line, explained Powell, were clear: Except for some land offering timber or pasturage, the far greater part of the land west of the line was essentially not farmable.

His conclusions amounted to a frontal assault on the land-grant agricultural system, still rooted in the 1862 Homestead Act’s stipulation that any American adult could receive 160 acres from the federal government (contingent on demonstrating an ability to live on the land and improve it). While that system might work well in Wisconsin or Illinois, Powell argued that the arid West could not support such homesteads. Those Americans flocking into the dry lands beyond the 100th Meridian might see a few good years with mild weather, but would ultimately see their dreams dashed by spindly crops, heartbreak, and bankruptcy. In one fell swoop, Powell had questioned the cherished Jeffersonian vision of an American republic filled with yeoman farmers tending small farms across the continent.

A 19th-century scientist’s bold reimaging of the American map upended deeply held assumptions—and presaged today’s global climate change wars.

A 19th-century scientist’s bold reimaging of the American map upended deeply held assumptions—and presaged today’s global climate change wars.

by John F. Ross ’81, P’12

Powell’s revolutionary map forced its viewers to imagine the United States not by way of political boundaries or even geological features, but in terms of climate. It was as startling then as the NASA photographs were in the 1960s that revealed the Earth as a fragile, living orb in the darkness of space. A climate-informed vision of the United States, noted Powell, argued against the willy-nilly development of the land. Powell did not disagree with American exceptionalism, but argued that the nation should take into consideration the physical characteristics of land, its climate, and resources as it developed the West. The land itself should have a say in the matter. No one would call him an environmentalist, but this hard-headed realist gave powerful voice to ideas of environmental sustainability and land stewardship.

In short order, railroad barons, settlers, western senators, and those intoxicated by Manifest Destiny bitterly denounced Powell’s claims. How could they let this naysayer stand in the way of American success? Eventually, after elaborating his positions in public documents, magazine and newspaper articles, impassioned speeches, and further clarifying maps, Powell would be hounded from his long-held position as director of the U.S. Geological Survey. But his unheeded warnings would prove eerily spot on as terrible droughts ravaged the West, which then erupted into the national tragedy of the 1930’s Dust Bowl and dislocated and ruined the lives of millions of farmers and settlers.

The concept of the 100th Meridian line and Powell’s prophetic words would live on. In the space age, astronauts in orbit peering down upon the United States could clearly see the very line that Powell had so brilliantly imagined in the previous century. Recently, a team of Columbia University meteorologists reexamined Powell’s line as to whether it had affected developmental patterns of settlement over time. It had. In the West today, population density is much less, farms are fewer and much larger than the East, and most of the land remains in public hands. The researchers pushed another step ahead: their data indicates that Powell’s line has shifted 140 miles east since the 1980s, the creeping aridity most likely the product of global warming.

All too often, we still ignore Powell’s prescient message, continuing to heedlessly develop southwestern cities with no long-term water strategies. Corporate farmers drill ever deeper to harvest, dwindling groundwater supplies. Engineers still devise elaborate, exorbitantly-priced canal systems (some, even, that cross mountains) to send water over many hundreds of miles to supply industrial farms and pacify thirsty city dwellers. The very river that Powell so loved—the Colorado—has become the world’s most litigated watercourse. No longer does the Colorado course through Mexico to the sea, but instead dries up at the border. The idea that water is a self-renewing, endlessly abundant resource, is a dangerous illusion, and Powell knew that.

Powell’s map, though nearly a century and a half old, still has the power to shake us out of our complacency and demand that we exercise more sustainable land and water practices. It’s especially critical now as Americans face the global ramifications of ignoring humanity’s effect on the planet.

John F. Ross is the author most recently of The Promise of the Grand Canyon: John Wesley Powell’s Perilous Journey and His Vision for the American West (Viking, 2018).

John F. Ross is the author most recently of The Promise of the Grand Canyon: John Wesley Powell’s Perilous Journey and His Vision for the American West (Viking, 2018).