Transforming the ‘Black Butterfly’

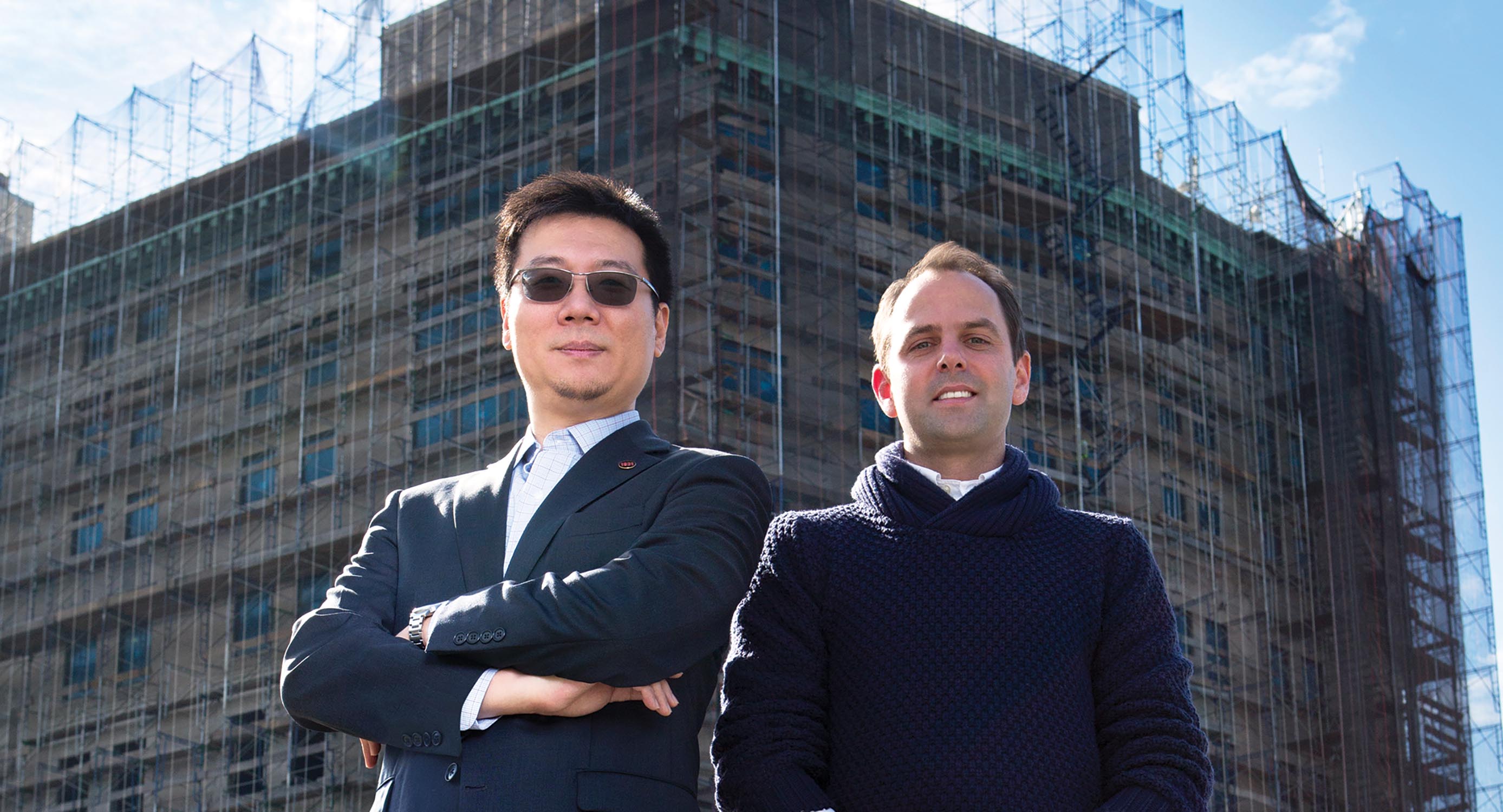

Baltimore City native and Johns Hopkins University Professor Lawrence Jackson ’90 created the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts to host sites of public engagement, through which the city’s African American communities and its largest private employer reveal their shared heritage and build for the future.

It was a chilly Friday night outside Red Emma’s, a West Baltimore bookstore named after anarchist political activist and revolutionary Emma Goldman. Inside the store, Lawrence Jackson ’90, a recently appointed professor at Johns Hopkins University, explained his new initiative to a jeans-and-dreadlocks crowd—graduate students, political radicals, Black nationalists, community organizers, teachers, and local professors.

A diplomatic, tapered man who wears a light beard, Jackson spoke unreservedly and plainly about the value of building new ties between his campus and other parts of the city, using anecdotes from his past. He presented himself as a person shaped by historical conditions requiring an ever more articulate form of struggle for social justice and equity in Baltimore.

Jackson built an easy rapport with the crowd. He has frequently said that although he holds a chair funded by billionaire presidential candidate Mike Bloomberg, works across established disciplines in English, history, creative writing, and Africana Studies—and contributes to the work of the Sheridan and Peabody Libraries—the distinguished chair would be more aptly named in his case after Freddie Gray, an unarmed young Black man who died in Baltimore police custody in April 2015. Gray’s arrest for riding his bicycle away from police officers and subsequent detention in a police van resulted in the severing of his spine. His death and the police department’s unwillingness to admit any wrongdoing precipitated a citywide riot, called in some quarters an “uprising,” after the ancient term for the revolt of the enslaved.

Jackson wrote about the uprising and the trial of the police officers in a Harper’s magazine article the next year called “The City That Bleeds: A Letter from Baltimore.” The essay was selected for the Best American Essays of 2017. He argued that the rioters, victims of a long history of regimented inadequacy, expressed themselves in the only way that made sense.

The Roots of the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts

For Jackson, 51, bending university resources into a more equitable relationship with Black communities (whose labor and land they have appropriated as a headright) has been the work of his last 30 years. Inside Red Emma’s, he spoke about his political consciousness, which was shaped even earlier in life through his experiences with police brutality, racial profiling, and the extreme levels of street violence in Baltimore. Mentioning his friend Donald Bentley, murdered during the summer of 1989, Jackson lamented the city’s half-century of crisis, its health care calamity, its fully unraveled educational system, and the debacle of public social life, requiring efforts beyond the capacity of the average politician.

“I didn’t think that universities were doing enough to share the most fundamental resources at their command to address the social crises that they claimed to have an investment in resolving,” he told the assembled group. “The Holiday Project is my attempt to modernize the college’s reparative social justice efforts, by creating a mechanism that brings faculty and students into reciprocal engagement with communities outside of the university’s Homewood neighborhood.”

Jackson wants to contribute to the effort to remake the city’s racial demographic polarity, the so-called Black Butterfly of African-American neighborhoods in the east and west portions of the city. Baltimore is controlled by a spine of financial investments and educational resources that ranges from the top of the northwest and down to the waterfront development of the southeast, a region that Jackson calls the “White Z.” During his job negotiations in fall of 2015, he made a pitch for startup resources to connect the Hopkins campus more genuinely and productively to portions of the Black Butterfly. He felt keenly the obligation to intervene in the gross resource disparity across racial lines in his ravaged hometown.

To drive through the southern tip of the city along Interstate 95 is to witness the difference between a modern, waterside, near-luxurious cityscape and a terrain lacking any visible sign of enhancement to the built environment in almost a century. The eastern areas showcase Hopkins’ extensive investments, but once beyond the Ravens football stadium, a fallow West Baltimore unfolds, home to the majority of the Black population and the Black political base. Jackson hoped to establish more durable passageways between racially and economically calcified territories in the city, with the idea that by opening a circuit of sharing—of reciprocity, of mutual regard—and an appreciative exchange of talent, he might amplify the dynamism of disparate areas.

To start, Jackson obtained an operational budget, three postdoctoral lines, and five dissertation fellowships. Two years later, he hired an associate director, Kali-Ahset Amen, an Emory University PhD in sociology who had lived in Africa and served as the managing director of Emory’s James Weldon Johnson Institute for Race and Difference. Named for Baltimore’s famed hometown jazz singer, the Billie Holiday Project began with a twin mission: to preserve the African-American print material archival record in the city and surroundings, and to create opportunities to share the research work efforts of Hopkins undergraduates, graduates, and faculty in the city. To cement the new partnership, Jackson donated his personal papers to the Sheridan Library special collections.

Tracing Ralph Ellison and “Invisible Man”

Baltimore has been a difficult place to plant a flag. Even with the success of television shows like The Wire and writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates, the city remains an unheralded place, on the edge between North and South, regarded by the national media as little more than a catalog of brutality. Its citizens struggle for identity between the more economically robust cities of Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia. The city’s history of mob street violence, which goes back to the 1820s, adds to its underdog, combative personality.

Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel “Invisible Man” was Jackson’s survival gear for the challenges of Baltimore during the violence and decay of the 1980s, which included the anguish of losing his own father to cancer in 1990. In his 2002 biography of Ellison, Jackson presented Ellison’s artistic dilemma in Harlem in the 1940s as the attempt to address the signal failures of Black leadership, whether in the Communist party, the Christian religious tradition, or the Republican and Democratic party leadership.

“In my era,” Jackson remembers, “Black people had just gained control of municipal governments, so the idea that something like police brutality or mass incarceration could exist under Black state’s attorneys or mayors was illegible to those who were not both experiencing it directly and reading the deep political history of the United States and the British and French colonial empires. We began using the tools at our disposal to make these situations legible. For me, that was through the life of Ralph Ellison, whose book (which is curiously not taught this way) is about the shooting of an unarmed Black guy from Harlem and then a riot which breaks out after the dead man’s funeral. You could just exchange the names Freddie Gray for Tod Clifton and Reverend Jamal Bryant (then minister of Empowerment Temple and eulogist at Gray’s funeral) for Invisible Man.”

For his biography of Ellison, Jackson conducted research in dozens of archival repositories and collected the stories from the writer’s relatives and intimates in Oklahoma, New York, and Alabama. In his subtle, detailed, painstaking work, Jackson provides the historical currents and political dimensions that shape the contours of unheralded and misunderstood cultural figures.

“Black artists are still considered raw material to be refined by an interpreter bringing to bear a mechanism or a tradition external to the creation of the art,” Jackson says. “Their own thoughts about their lives and their cohorts, the communities that produced them, and the contemporaneous evidence that they left was always ignored or undervalued.” In the 1980s and 1990s, Ellison was being interpreted by conservative cultural and social forces as an icon of Black assimilation into the American mainstream, and an obliteration of a radical political agenda. “By piecing together scraps of his materials that had been available previously, I came to believe that his artistry stemmed profoundly from two sources: an enduring Black artistic project emanating from Black home life, and a radical political agenda.” Jackson provided a novel description of Ellison, who later was shown to be a card-carrying member of the Communist party, in the context of Harlem and a left-wing artistic movement.

Jackson learned, with the publication of the Ellison book, that life-writing made an impact beyond the academy. Through archival recovery, he could usefully aid Black people whose efforts to create narratives for community empowerment were marginalized. Democratizing the episteme, and dismantling the stranglehold of powerful interests in claiming single, unitary, and monolithic historical and cultural visions, was a key part of Jackson’s intellectual task. When he completed the Ellison project, Jackson decided to write the life of Chester Himes, a forgotten radical novelist. Traveling to Paris for research, he realized that the formative era shared by Ellison and Himes, the 1930s and 1940s, had not had its main intellectual and artistic corridors defined. He made a detour. The two award-winning books, The Indignant Generation: A Narrative History of African American Writers and Critics, 1934–1960 (2011) and Chester B. Himes: A Life (2017), were his work for the subsequent 15 years.

The Draw and Downsides of Higher Education

Jackson was born in Sinai Hospital and raised in northwest Baltimore, three blocks from the last aboveground subway station on Cold Spring Lane. His parents chose a hospital they were unfamiliar with because during his birth year the Hopkins hospital, the city’s best, remained racially segregated. He lived in a close-knit African-American neighborhood of schoolteachers and postal workers, dry cleaners and steel mill workers. On Christmas Day, the families and children exchanged gifts along the block. A cradle Episcopalian, Jackson was baptized and confirmed at the St. James Episcopal Church, the home of his mother’s family. The church in Lafayette Square was founded in 1824, the first Black-run Christian denomination church below the Mason-Dixon line, later attended by Thurgood Marshall, a former associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Every Christmas Eve, the Jackson family decorated the church, hanging the heavy roped evergreen garland and fastening red ribbon bows and spruce needle wreaths along the hammer-and-beam buttresses of the Gothic interior.

The son of two parents whose professional careers were spent primarily at city and country social welfare agencies, Jackson can’t remember when he wasn’t doggedly contributing to the political process and service projects.

“On the election days in the 1970s, primaries and general, our parents would take us out canvassing for candidates, handing out flyers and leaflets all day at polling places for neighborhood politicians running for office,” he recalls. “It took all of the 1970s to win election in northwest Baltimore of Black candidates, although Black people were more than 50 percent of the electorate.”

Jackson received a congressional nomination to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point, but a new guidance counselor at his high school steered him to Wesleyan. He liked that the college—the faculty, the students, that part of the country—was entirely unknown to him. In fact, what he did know was troubling. He had visited Middletown in the spring of 1986 with his mother and father and walked past a car whose driver had said matter-of-factly, “And there goes another nigger.”

During his time as an undergrad at Wesleyan, a confidently activist campus, Jackson led fellow students in a study of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Students screened films and brought to campus New Haven Panthers to take the class beyond staid reading lists. Jackson found this environment, dedicated to creating new knowledge, intoxicating; it felt reminiscent of the spirit of activist intellectual life that followed the 1969 militant student takeovers of campus buildings. Aware of reports identifying the decline in the Black professoriate, he decided to pursue a doctoral degree.

“The chic crowd from college were interviewing at McKinsey, investment banks and entertainment companies, or going on to joint law school and MBA programs, so getting a PhD seemed like an incredibly radical move.” What is today called African American Studies would have been a desirable area of study for him, but it did not exist in the academy at that time. To pursue a degree in English required Jackson to undertake more work in English literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. “Initially I thought it was like being forced back into slavery. But reading the foundations of the language brings some advantages to your writing.”

When he completed his doctorate at Stanford University in 1997, he accepted a job at Howard University, with an annual salary in line with Howard’s other entry-level positions, regardless of education: $32,750. After taxes and student loan repayment, the pay barely covered the groceries and keeping a car on the road. Living in Washington was out of the question. For the five years he taught there, a time during which he won the Ford Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship and a perch at the Du Bois Center at Harvard University, Jackson lived in Baltimore on Pimlico Road.

“I didn’t see a dentist for more than ten years. I did all of my home repairs myself, from demolition and roofing to plumbing and electric wiring.” The neighborhood on Pimlico was showing signs of devastation. “I had known my next-door-neighbors since childhood, but they had fallen into heavy heroin use. We had rats the size of cats climbing fences.”

Subsequently, he was invited to join the faculty at Emory University in Atlanta, where he remained for 15 years before moving to Hopkins.

Hopkins and the Holiday Project

Jackson had worked patiently through the scraps of Ellison’s materials from the 1940s, skills used again to overcome the archival lacunae in the materials from Chester Himes, whose manuscripts, papers, and letters had been spottily preserved. Black writers’ effects were traditionally undervalued and frequently discarded. When he began the Holiday Project at Hopkins, he had several collections in mind that were in peril and might be appropriate for university acquisition, including photographs, politicians’ libraries, and literary materials. But he had an objective beyond mere acquisition: to build a collectivity that would share information and acquisition methods and have a broader impact on the preservation of Baltimore’s Black history.

Jackson hosted a 2017 symposium that attracted more than 60 participants representing organizations that ranged from the Maryland Historical Society and the Reginald Lewis Museum of Maryland African-American History & Culture to historic Black churches and community groups and the Library of Congress. The open forum brought together historically white institutions and their Black counterparts to discuss the problems of unequal resources and ethically engaged collecting, which had never happened before in the city.

The capstone of the preservation efforts occurred in October of 2019, at the gala opening of the John Clark Mayden Photograph Exhibit, and publication of the book Black Lives. Mayden, the former Baltimore city solicitor, started taking photographs when he was a college student in 1970. His aching, loving photographs of Black people along historic Pennsylvania Avenue represent the bridge between the mid-twentieth-century Black photographer Paul Carter Henderson and the work of contemporary photographers Devin Allen and Shan Wallace. Mayden’s artwork of Black presence is essential to understanding fully the aesthetic dimension of Black revalorization rising from the political struggles of the 1960s and 1970s. The papers of a poet and editor and multiple civil rights pioneers are also under consideration.

The Mayden Exhibit, held at the Peabody Library with its heavy wrought-iron Neo-Greco columns and occupying the same square as the oldest monument to George Washington in the United States, yielded a genuinely racially mixed audience, unusual for a Johns Hopkins public event.

The Billie Holiday Project has produced other tangible results. The Hopkins Pathways program began in May of 2017, with a group presentation by four English department graduate students. At Baltimore City College, the Maryland Historical Society, and Morgan State University, the students shared digital maps revealing the historical life of Marylander Frederick Douglass.

Seasoned researchers have given lectures in the Helena Hicks Speakers Series, named after the Black woman who led college students in a lunch counter sit-in desegregation movement in 1955, five years before the sit-in of Greensboro, North Carolina. The series brings Hopkins faculty to prominent westside churches, like Union Baptist Church on Druid Hill Avenue, the home of Rev. Harvey Johnson’s famous Liberty League (the forerunner of the NAACP), and Sharp Street United Methodist, a church that goes back to 1787 in the city and whose founders were present at the creation of the African Methodist Episcopal religious denomination. In the fall of 2021, local literary legend D. Watkins, editor at large for Salon, has been invited to be the Holiday Project’s first postdoc as writer-in-residence. Jackson hopes, in five years, to have turned the project into an institute, the gateway and clearinghouse between the college and the city, with classrooms and viewing space, at a stand-alone site, a cluster of connected rowhouses on historic Druid Hill Avenue.

Working Through Contradiction

In September of 2019, the Holiday Project hosted a jazz concert, its largest public affair, in the middle of Lafayette Square in Sandtown, a now blighted neighborhood where Freddie Gray grew up. A small park on Arlington Avenue commemorates children killed in the lethal violence that accompanies the open-air drug markets that dot many of the neighborhood’s intersections.

The square has an important history for Black Americans as an anchor of Baltimore’s African-American religious life, hosting St. James Episcopal Church, one of the city’s three Black congregations dating its origins to before 1825; St. John’s AME Church; Metropolitan Methodist Church; and Star of Bethlehem Spiritual Temple. Billie Holiday herself lived just off of Lafayette Avenue, and the fountainhead of the city’s jazz heritage was at the Royal Theater (1922–1971), located at Pennsylvania and Lafayette Avenue.

On the Saturday following Labor Day and in perfect weather, Jackson addressed the crowd from a soundstage. He reminded the audience about the purpose of the project, named after Holiday, who knew the neighborhood well, as it was the backdrop of one of her early personal tragedies.

Working on his projects and programs in historic Sandtown, ground zero of the uprising, is consequential to Jackson. What stands out most to him about the event—attended by 500 people—were two Black men from the neighborhood, both in their 60s, seated comfortably in lawn chairs close to the stage.

“This concert was principally for this community,” Jackson proclaimed, “and we shared with the outsiders our customs of appreciation and value.”

Last year, Jackson was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and is now at work on a book that digs into the ambivalent position of residing in one of the city’s elite neighborhoods while trying to work with the power of the grassroots. The work is rife with tension: Is urban social transformation possible within the confines of a broad neoliberal political agenda? How do people of good conscience ride out this contradiction, which presents privatization and white gentrification as the resolution to poverty, dilapidated housing, inadequate health care, and a crumbling school system?

However trying, this new direction complements and continues to inform the Holiday Project, which, as Jackson describes it, “is going to ride the line between institution and radical independence as long as we can balance that tension.” The pursuit of an ever more articulate form of struggle for social justice and equity in Baltimore he spoke about at Red Emma’s has coincided with a powerful movement for change in the United States that bodes well for the future of the project, which Jackson ties firmly to Hopkins’ historical roots.

“We don’t want to remake the city in the image of Hopkins, and mercifully our task is not as difficult as reversing the institution’s course,” he says. “We have only to help it live up to the reparative work that was so obvious and necessary to its founder, who launched an orphanage, hospital, training school, and a college in the wake of the nation’s most important watershed in a century and a half—the emancipation, citizenship, and enfranchisement of the African.”

Find out how you can support the work of the BHPLA in Baltimore by contacting Dr. Kali-Ahset Amen at liberationarts@jhu.edu.